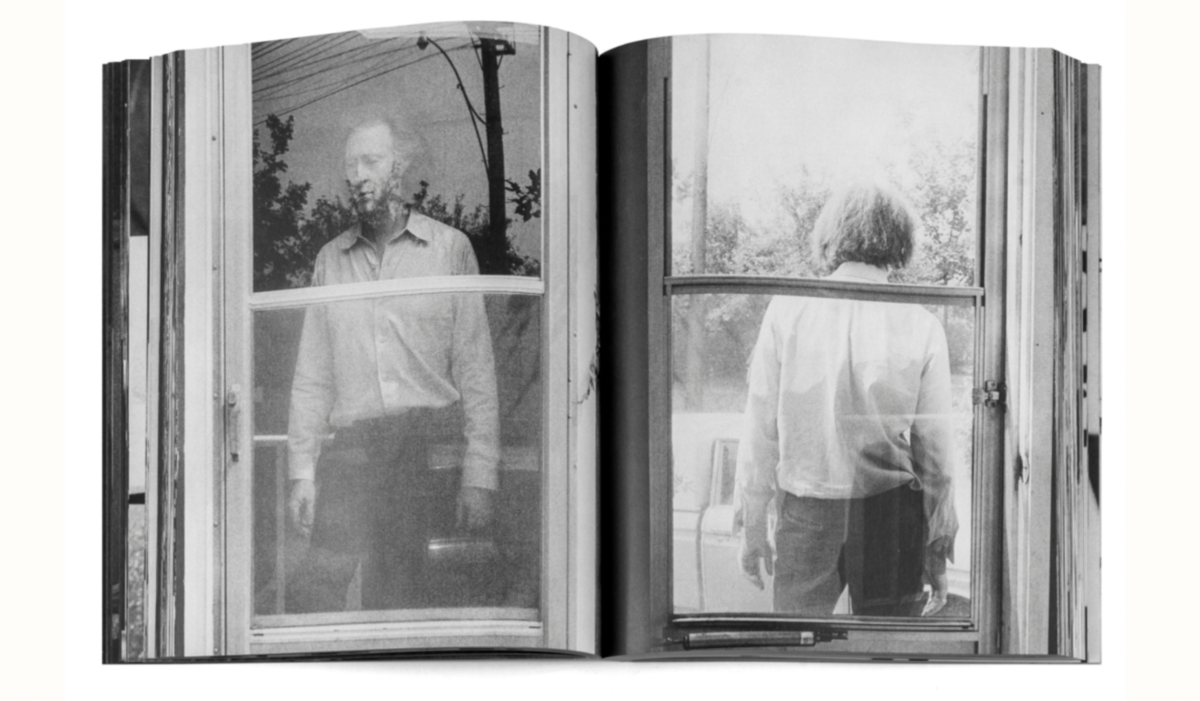

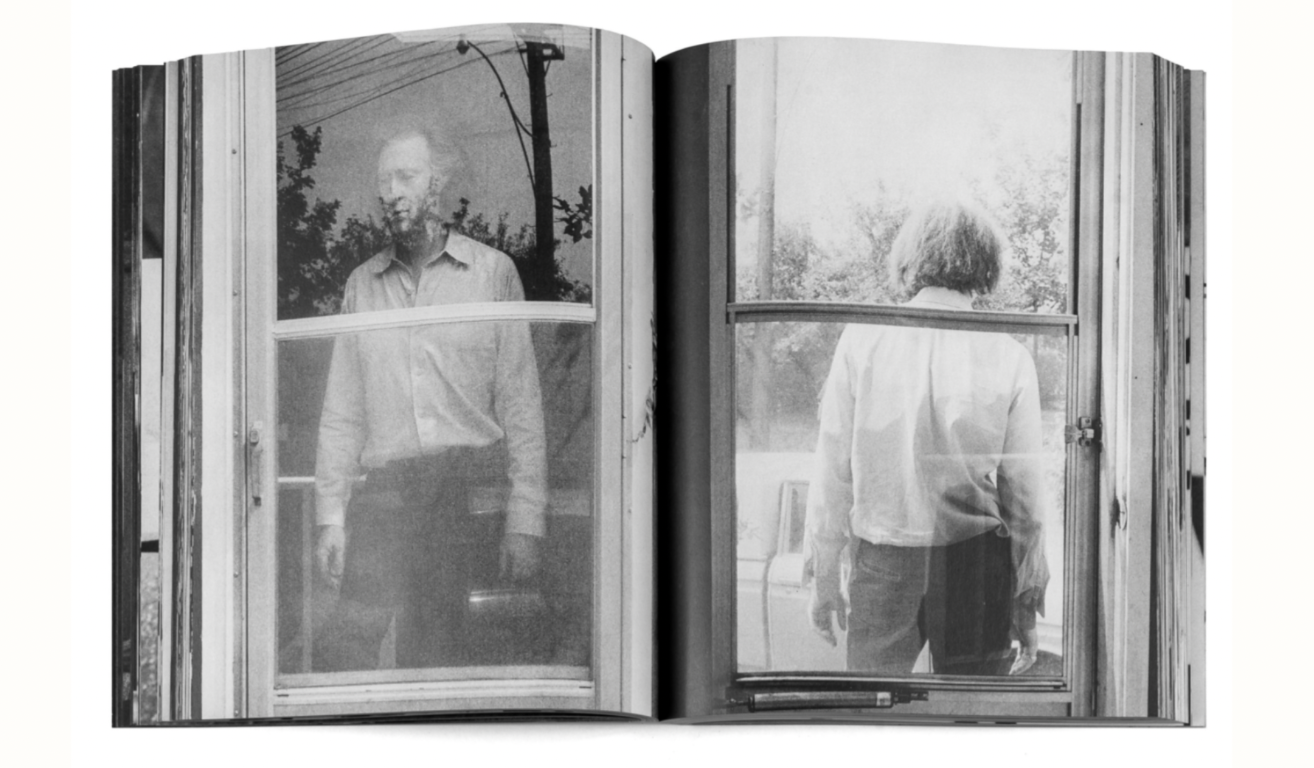

Cover to Cover by Michael Snow, Primary Information/Light Industry, 2020. Softcover facsimile reprint of 1975 original.

My paintings are done by a filmmaker, my sculpture by a musician, my films by a painter, my music by a filmmaker, my paintings by a sculptor, my sculpture by a filmmaker, my films by a musician, my music by a sculptor … who sometimes all work together.

—Michael Snow, 1967

Throughout his artistic career, the Canadian artist Michael Snow (1928–2023) was known for his innovative and experimental approach to art, working across the mediums of film, photography, painting, sculpture, and music. Born in Toronto, Snow received his artistic education at the Ontario College of Art, where he studied design while also developing his skills in painting and music. After completing his studies, he traveled to Europe and returned to Toronto in 1953, where he had his first solo exhibition. While working at Graphics Film at the time, Snow developed an interest in film and married artist and filmmaker Joyce Wieland. Snow and Wieland went to New York in the early 1960s, when he started working on the Walking Woman series, a long-term project in which he used various artistic mediums, including sculpture, photography, and performance, to explore the representation of a woman walking. That was also the time when Snow produced his now most-known experimental films, including Wavelength (1966–67), which became Snow’s signature work, and which I had a chance to watch for the first time at Anthology Film Archives in 2011.

The forty-three-minute film is comprised of several reels of 16 mm film footage recorded inside a New York apartment with a camera that is static yet slowly zooming forward. By gradually reducing the angle of view on the apartment’s space, the camera’s zoom gives the impression that the opposing wall of the apartment progressively approaches the viewer at the same time as buildings across the street viewed from the apartment’s window appear to flatten. Notably, the minimal film has four sequences with human characters. They, however, unlike human episodes in narrative films, do not form a linear story. In the first sequence, a group of individuals carrying a bookshelf enters a room; soon after, two women arrive, talk, and listen to the radio. Several minutes later, a man (played by noted experimental filmmaker Hollis Frampton) enters the frame and suddenly collapses on the floor. The camera remains completely indifferent to these event and proceeds to zoom towards the opposite wall of the apartment, eventually leaving the corpse of the dead man off-screen. Finally, the female character (played by acclaimed film critic Amy Taubin) enters the frame to call someone to inform them about the deceased guy in her apartment. Despite the suspense felt off-screen, the photograph of ocean waves pinned on the wall ultimately acquires the central space on the screen, resulting in the opening of another illusionary horizon, this time within the photograph of the ocean. The film’s zoom into the photograph seems to allude to the moment when the past and the future, the beginning and the end of the film, coincide. This hypnotic moment, reinforced by the intense sound design, completely mesmerized me as I watched the film in the theater. Only later did I realize that many of Snow’s works similarly demonstrate his interest in centrifugal framing, letting events exist beyond the borders of the screen, almost responding to the early theory of André Bazin, who argued that “the outer edges of the screen are not, as the technical jargon would seem to imply, the frame of the film image. They are the edges of a piece of masking that shows only a portion of reality.”1 As Jonathan Rosenbaum adds, Snow in his films “makes ‘everything’ interesting, transforming every discernible element in its path into an object of significance.”2 Importantly, Snow’s experimentations with on-frame and off-frame spaces encompassed not only film, but also other artistic mediums he worked with, including sculpture, paintings, and photographs.

In an interview with Alan Licht, Snow acknowledged that he had always been fascinated by blending mediums and making what he termed “painterly photographs,” “photographic paintings,” and “filmic sculptures.”3 In his “painterly photographs,” Snow approached the medium of photography by employing material substances to enhance his photographic prints, whereas his “photographic paintings” were made with the help of a photo camera. Making his “filmic sculptures,” Snow treated film as sculpture, exploring the relationships between the time and space of film projection and other techniques of film dispositif to manipulate and enhance the viewer’s perception of the moving image. Snow’s “filmic sculptures” include films like <—> (1969) and La Region Centrale (1971). The former was shot in and outside a classroom with the camera panning and tilting at varying speeds and frequencies in order to produce a sculpture of time and movement. The latter is an (in)famous three-hour-and-ten-minute film comprised of several long takes that were recorded on a mountain in Quebec, Canada. Snow used a motorized tripod to make the film, which enabled the camera to pan, tilt, zoom in and out, and spin in all directions and at different speeds, providing a distinct more-than-human perspective on the mountainous landscape. La Region Centrale is notable for using the camera as a sculptural tool to create a sense of the landscape as a three-dimensional space overcoming the limits of habitual vision. (As Jonas Mekas recalled, many viewers would need some time to regain normal vision after the initial New York screenings of La Region Centrale.) The tensions between stasis and movement, text and image, control and spontaneity remained Snow’s concerns throughout his filmmaking career, fueling his never-ending experiments in blending different formats and mediums of art, as seen in films such as One Second in Montreal (1969), which was entirely composed of photographs, Side Seat Paintings Slides Sound Film (1970), which used imagery from paintings, and So Is This (1982), which was based on snippets of text meta-critically appearing on screen in time. WVLNT: Wavelength For Those Who Don’t Have The Time (2003) was one of the latest iterations of Snow’s “filmic sculptures,” which consisted of simultaneous superimpositions of images (and sounds) rather than the sequential progressions characteristic of the original Wavelength. As a consequence, the new version of the film is thirty minutes shorter than the original, becoming a playfully stated commentary on contemporary conditions of visuality and its perception.

Given the current state of the moving image, when economic and institutional boundaries are being redrawn, Snow’s open explorations of the relationships between film, photography, painting, and sculpture will undoubtedly continue to inspire contemporary artists and experimental filmmakers for generations to come.

André Bazin, “Painting and Cinema,” in What Is Cinema?, vol. 1, trans. H. Gray (University of California Press, 2005), 166.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, “WAVELENGTH,” Monthly Film Bulletin 42, no. 493 (February 1975).

“Michael Snow by Alan Licht,” BOMB, March 12, 2014 →.