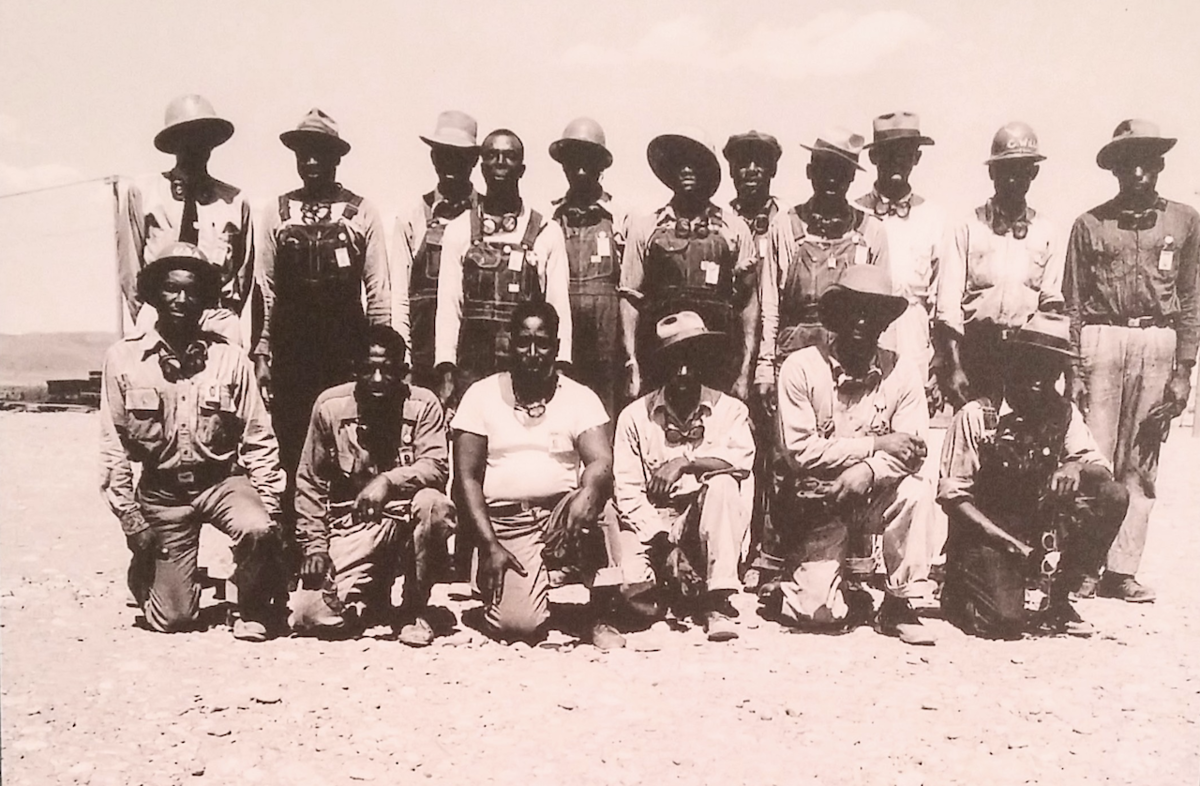

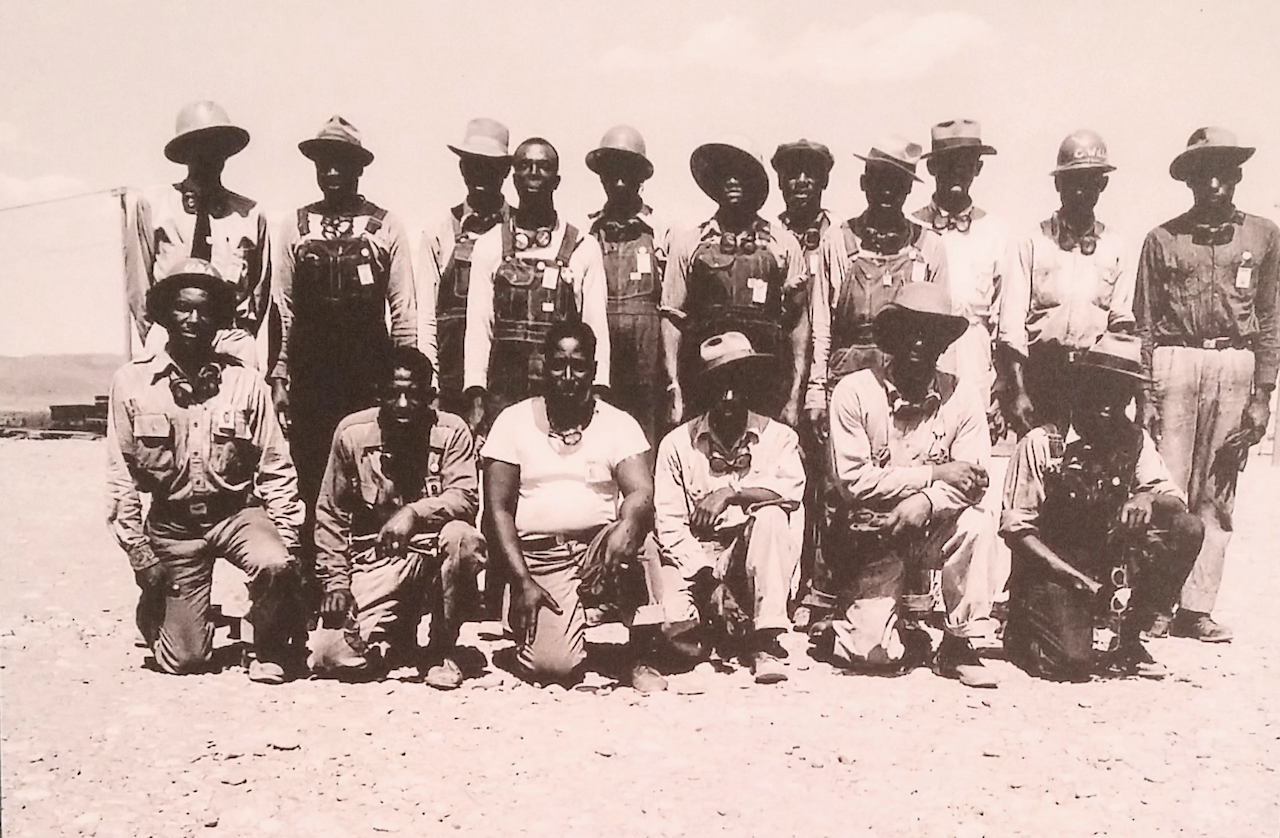

A group of Black construction workers at Hanford, Washington State, c. 1944. Courtesy of the African American Community Cultural and Educational Society.

In 2008, three years after Knopf published American Prometheus—the biography that director and writer Christopher Nolan adapted for his blockbuster biopic Oppenheimer—Kyoko Hayashi’s novella From Trinity to Trinity quietly made its transition from Japanese to English by way of a translation by Kyoko Iriye Selden, a Japanese American scholar. The nameless narrator of this short but lyrical work miraculously survived, like its author, the second atomic bomb that the US dropped on Japan. She was only fourteen and working in a Mitsubishi weapons factory when, at 11:02 a.m., Fat Man exploded and instantly killed thousands, and then over four months killed tens of thousands, and then over several years killed hundreds of thousands, with millions more physically and psychologically damaged for a generation. Hayashi Kyoko’s life was then visited by a second miracle. Despite direct exposure to radioactive materials, much of which fell from the mushroom cloud that hung over the factory, she died in 2015 at the old age of eighty-six.

Selden’s 2008 translation of From Trinity to Trinity was published in the Asia-Pacific Journal, a small academic publication. In 2010, a new translation was completed by a Japanese American dancer and choreographer, Eiko Otake, and published in a slim book (sixty-one pages) by New York’s Still Hill Press. The introduction to the new translation described the novella as continuous with Hayashi’s other important contributions to Japan’s atomic bomb literature. Her works tended to be semi-autobiographical and earnestly poetic, and to involve hibakushas (atomic bomb survivors).

In From Trinity to Trinity, the nameless hibakusha travels to ground zero of the atomic age, Trinity Site, New Mexico. She wants to see the source of her lifelong “A-bomb disease.” Here, on July 16, 1945, at exactly 5:29 a.m., the US government successfully transformed a mass-energy equivalence equation, formulated and presented in 1905 by a patent examiner based in Zurich, into a weapon of unprecedented power. The development of this weapon is, of course, the subject of the third film in what I call Christopher Nolan’s “Physics Trilogy.”1

When the elderly hibakusha in From Trinity to Trinity reaches the core of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, the National Atomic Museum, she finds a section that “displayed many items such as postcards and United States Air Force badges” and “[a shredded American flag] displayed in a glass case.” And there “was also a photo panel that showed the history of the ‘ATOMIC BOMB,’ which, together with the history of the military base and the Air Force, made a three-power combination. On the first wall was a photo of Dr. Oppenheimer, acknowledged father of the atomic bomb. He was the first director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, a nuclear power research facility.” (Cillian Murphy plays Oppenheimer in Nolan’s film.)

What immediately strikes the unnamed narrator is the whiteness of the visitors. No Blacks or Mexicans or any other race are there. She is the only POC in the museum. And she isn’t American. The novella suggests that a large number of white Americans did not see American military power in the same way as other members of their society. Indeed, one might speculate that the other groups (minorities) actually saw American militarism (which is why they felt no need to visit the museum), while a lot of white Americans did not. In this sense, the latter were akin to zombies, which embody a way of visiting the past without haunting it. Only ghosts see the past. And ghosts can only come from the future.

But why do white Americans fail to haunt the Trinity site in the way that the nameless narrator does? Why are they zombies? Patriotism. That is the bite of zombification. As Richard Rhodes points out in his masterful The Making of The Atomic Bomb (1987), the white working class directly participated in the event that changed the world. The plane that dropped the Little Boy atomic bomb on Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. was named after the white working-class mother, Enola Gay, of its pilot, Paul Tibbets.

European and white American intellectuals certainly developed the weapon, but white members of the working class pulled the trigger. The structure of this relationship is, of course, not isolated to the world-historical explosions that ended the Second World War. It extends all the way back to the foundation of American capitalism—the plantation days, the ships, the whips, the chains, the bloodhounds, the hush puppies, the North Star. If the tight relationship between upper-class whites and working-class whites were excised from American history, then the hibakusha would have found nobody in the National Atomic Museum, except ghosts like herself.

As I explained in the essay “Who Haunts?,” those in the past cannot haunt the present because they are really and truly dead.2 The dead can do nothing. The end of life is everything. Those who lived and died on slave plantations are gone for good. And the Native Americans poisoned to death by the radioactive windblown dust ejected by the Trinity test will never, to use a disturbing Shona gesture, speak again (this is expressed by running a finger over closed lips: wordlessness is death itself). Those vaporized at 11:02 a.m. in Nagasaki are never coming back. But, while alive, Kyoko Hayashi could and did go back. She could haunt Oppenheimer.

But there is something I left out of “Who Haunts?”: a description of what exactly makes haunting possible. Haunting as a return of the past has not always taken place in the world. There was once a world with little to no haunting. A member of, say, the Jōmon people (in ancient Japan) could not haunt American Indian pueblos (precolonial America), and vice versa. Why not? Because there was no time path from one to the other. Each group had its own form of time that was intimately and ultimately tied to its area, to its geography, to its vegetation and seasons. The haunting we find in From Trinity to Trinity is specific to our times.

Capitalism made real (meaing living) haunting possible. Without this economic system, the time travel we find in From Trinity to Trinity—and, as I pointed out in “Who Haunts?,” in Octavia Butler’s Kindred—would be impossible. We can go back to the plantation because it’s unified with our time by capitalism, which, as Marx put it in his famous rock song,3 has to “nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere” in order to “constantly [expand the market] for its products.”

Capitalism makes Newtonian time a reality. Indeed, Newtonian time, universal time, time once and for all, and the subjectivity that the physicist and philosopher Karan Barand’s calls “time being” are only conceivable in this social formation.4 Its “empty” and “homogenous” time makes haunting compossible.5 Think of it this way: in the sci-fi book series and TV show The Expanse, “the Ring” is a wormhole developed by a mysterious and technologically advanced civilization to subject more and more of the galaxy to the domination of time. The Ring allows you to go anywhere you like in the Milky Way—which is about a hundred thousand light years from end to end—in a matter of months. Capitalism’s Newtonian time opens the past to those who are living now and also tomorrow.

This fact does not in any way diminish the power of haunting. Capitalism is as real as anything else out there: a stone, a star, a smell. And because capitalism is real, the haunting is also real. This is the nature of the universe. “[Capitalism] is an actual entity, so is the most trivial puff of existence.”6

Let’s return to the absence of Black people in the atomic bomb museum. They might not have been there at that time, but they certainly were in a history synthesized by globalized market exchanges.

The Manhattan Project had three key locations. One was the Trinity Site in New Mexico, where the bomb’s theorists worked. Another was in Oakridge, Tennessee, where uranium was enriched. The third was the Hanford Site in south-central Washington State. Army Lieutenant General Leslie Groves, who picked Oppenheimer to beat the Germans in the race to the ultimate weapon (and who is played by Matt Damon in Nolan’s movie), selected Hanford because, unlike Oakridge, there was lots and lots of nothingness there. Nothing but some farmers, Native peoples, wild animals, dust, and wind. The production of plutonium at the Hanford Site transformed, in Niels Bohr’s eyes, the whole of America into a factory.

Richard Rhodes writes: “Niels Bohr had insisted in 1939 that U235 [Uranium-235] could be separated from U238 [Uranium-238] only by turning the country into a gigantic factory. ‘Years later,’ writes Edward Teller, ‘when Bohr came to Los Alamos, I was prepared to say, ‘You see … But before I could open my mouth, he said, ‘You see, I told you it couldn’t be done without turning the whole country into a factory. You have done just that.’”7 (Benny Safdie plays Teller in Oppenheimer).

The exploitation of the “nothingness” at the Hanford site—located along the Columbia River where it bends toward the Oregon-Washington border, ultimately emptying into the Pacific Ocean—needed a massive labor force. But there was a problem: a large number of the privileged source of this labor, white American men, were fighting and dying in Europe and Asia. The solution? The US government was forced to hire Black labor at a living wage. The story of this moment in US history was covered by a 2015 exhibition at Seattle’s Northwest African American Museum, “The Atomic Frontier: Black Life at Hanford.”

The curator of the exhibition, Jackie Peterson, explained in an interview series titled “Voices of the Manhattan Project” that this region of Washington, of nothingness, had, before 1943 (the year that construction began on the plutonium factory), thirty black people. In a matter of months, there were six thousand. That number kept growing because the corporation that the government contracted to develop the site, Dupont, had to pay Black people the same as white people. This was a big pull for Black Americans across the country. They often traveled thousands of miles to get some of that bomb-making money.8 But equal pay did not mean racism came to an end. As Peterson points out, even here, in the middle of nowhere, flagrantly racist “sundown laws” were imposed:

Because Washington State had no legal segregation, a lot of it was citizens kind of banding together and acting on their own. Kennewick [a city in the Hanford area] became a sundown town. Kennewick is connected to Pasco via a bridge over the river. A lot of places across the Midwest and the Pacific Northwest worked with—a lot of citizens worked with—their local law enforcement to essentially keep African Americans out of their towns during certain parts of the day. A lot of these towns became known as sundown towns, because African Americans were not permitted to be in those towns after the sun set. This was enforced by the Kennewick Police Department, and they would be sitting at the foot of the bridge. If you were an African American and you would try to cross the bridge into Kennewick after sundown, you would be turned back. If they saw an African American person within the City of Kennewick after sundown, police would follow you around and ensure that you left.9

After the war, many of the Black workers moved to Seattle or back East. The present Black population in the Hanford area is very small. Their participation in the Manhattan Project is almost forgotten, and will certainly never be the subject of a major Hollywood picture. But, if you are living, and not a zombie (Hanford, like Oakridge and Trinity, has tourist attractions for that low-grade species of haunting), you can visit Hanford and ghost the buildings that long-gone Black Americans helped to construct, the halls where they danced, the restaurants where they ate and drank, and the towns they were forced to avoid.10 Why? Because Black laborers,11 like the scientists at the Trinity Site, were in time, universal time, empty time.

On November 30, e-flux Screening Room presents the New York premiere of Charles Mudede’s film Thin Skin.

The first film is Interstellar, which dramatized, in very popular terms, the universe described by Einstein’s special and general relativity. The second is Tenet, which transformed the Dirac Equation—the first equation to posit antimatter—into a fantasy. (Paul Dirac first pictured antimatter as holes in reality.) The third film, Oppenheimer, owes its substance not so much to J. Robert Oppenheimer as to the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, who, played by Kenneth Branagh, is on the periphery of the film’s plot. Bohr’s work in the quantum realm led directly to the correct interpretation of a German experiment that freaked out the physics world in 1938—the nuclear fission of uranium.

Charles Tonderai Mudede, “Who Haunts?,” e-flux journal, no. 139 (September 2023) →.

Watch Raul Peck’s masterful film Young Karl Marx to the end to get this reference.

Karen Barad’s essay “Troubling Time/s and Ecologies of Nothingness: Re-turning, Re-membering, and Facing the Incalculable,” in Eco-Deconstruction: Derrida and Environmental Philosophy, ed. Matthias Fritsch, Philippe Lynes, and David Wood (Fordham University Press, 2018), had a huge influence on the thoughts explored in this essay. However, Barad and I part when it comes to hauntology. She uses it in the strict Derridean sense of the past haunting the present. I use it to show that haunting is the condition of being alive, specifically in capitalist universal time.

Walter Benjamin’s “empty, homogeneous time” is found in his posthumously published “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” In my reading of Gottfried Leibniz’s metaphysics of compossibles, they are what determine what can and cannot pass from the virtual into the actual.

The actual quote, from Alfred North Whitehead’s Process and Reality, is: “God is an actual entity, so is the most trivial puff of existence.”

Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, 25th anniversary ed. (Simon & Schuster, 2012), 500.

Many (if not all) of the Black workers didn’t know the real purpose of the Hanford Site, the real reason why the pay was so good there.

“Jackie Peterson Interview,” Voices of the Manhattan Project, 2018 →.

To this day, the three cities that consolidated near the Hanford Site—Richmond, Kennewick, and Pasco—are segregated. The old Black side of Pasco is now the Latinx side of town. Indeed, Pasco was the first Spanish-majority city in Washington State. The Hanford Site itself is still poisoning people and wildlife in and around the Columbia River.

This includes the Black African laborers in the Shinkolobwe mine, a uranium mine in the Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) that supplied the Manhattan Project. They too were a part of the capitalist totality and, as a consequence, were, like us today, time beings.