From parliamentary structures and other protocol architecture to World Expositions, history is replete with buildings whose interiors have served as the ultimate theatres of power. In these projects, art, architecture, and design ascend to the role of choreographer and function as an intricate cinematographic apparatus, inscribing authority and directing its gaze. These government and political commissions of architecture and art often evolve into scenographic machines for new ideological beliefs and political affiliations.

Contemporary socio-political crises, accompanied by the ascent of far-right ideologies and populism, have exerted a profound influence on cultural production worldwide. Numerous artworks and cultural productions have come to represent certain political identities; museums and galleries frequently align their programs with politically heightened national and ideological directives. Within this context, the delicate relationship between political authority and culture is most frequently presented in the form of commissions. However, there is another bond between the two: the political gifting of culture. In this paradigm of the gift economy, art and culture are not just pawns in soft power strategies, but are themselves also complicit in the production of political scenography.

Marcel Mauss eloquently describes how the practice of gift-giving adheres to a stringent rule system, whether explicit or implicit, including obligations linked to receiving a gift and the acknowledgement of reciprocity.1 However, within the framework of gifting through political and (trans)national authority, a pressing question arises: how do the established sets of relations morph when the original recipient or the gift giver themself undergo an ideological transition, transformation, or cease to exist altogether? How does the political landscape of gifting transfigure into new sets of socio-political relations between the parties inheriting the cultural capital of the initial transaction?

The Gift is a three-channel film that brings together case studies of political gifts of culture made during moments of crisis in the identity formation of Europe and its political interlocutors. Through its assemblage of historical ready-mades, the film shows how universal and timeless the hijacking of culture by ideology is.

A Synopsis

The story tells of a nation that is broken, and in order for it to heal, a perfect gift must be created, one that can reconcile towering divisions in times of deep social and political crisis. A competition is planned to find the most suitable solution. Four judges summon three male allegorical figures to take part: an Artist, a Diplomat, and an Engineer. Each is tasked with presenting a vision for a gift that is both aesthetically impressive and politically adequate to surmount the crisis. The competition aims to question whether culture, when in service to a nation, can be anything but a Trojan horse for covert political interests.

The three men are judged and scrutinized by allegorical embodiments of the Four Freedoms.2 As the evaluation progresses, the Freedoms grow increasingly assertive, delivering a verdict of complicity to the men in the implosion of culture. They signal the destruction of the symbolic tie between state and culture, a reminder of past ideals and their collapse in the face of rising populism.

The Architecture

Architecture embodies the symbolic grounds of the film’s protagonists as they echo words drawn from archives surrounding the construction of these theatres of power and the socio-political context of their creation. All of the buildings featured are political gifts themselves: the French Communist Headquarters in Paris is a gift from architect Oscar Niemeyer; the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw is a present from Stalin to the new Soviet state of Poland; the Palace of the Nations is a gift from the city of Geneva to the international community, and its interiors gifts from members of the League of Nations; Mount Buzludzha is a citizen-funded tribute to the Socialist movement in Bulgaria. Within the film, the buildings merge into a singular architectural entity, serving as a cinematographic device that simultaneously channels and choreographs all the movements and actions of the characters.

Oscar Niemeyer’s Communist Party (PCF) Headquarters in Paris was a gift from the architect, who worked pro-bono on the project. Niemeyer, having collaborated with Le Corbusier on the 1952 United Nations Building in New York, and having contributed to significant projects like the National Congress and iconic government buildings in Brasilia, possessed substantial experience of navigating the intimate relationship between architecture and political power. After the right-wing military dictatorship overthrew the Brazilian government in 1964, Niemeyer entered self-imposed exile in Europe. His design for the PCF headquarters emerged at a critical juncture for the party, functioning largely as a material gesture of consolidation as the party dealt with significant losses during the 1968 French election.

Throughout French history, architecture and decor have consistently served as symbols of state power, from the opulence of the Palace of Versailles to Pierre Paulin’s transformative 1971 presidential office interior. The architecture of the PCF headquarters features an open and transparent assembly hall that appears to break with the burden of antiquated political style, propelling itself into the future. Niemeyer’s preoccupation with formal unity resulted in a work that seemingly transcended political divides, creating a perfect scenographic device for politics.

The Palace of Culture and Science—or, as it was originally named, the Joseph Stalin Palace of Culture and Science—was built in Warsaw between 1952 and 1955 by nearly 10,000 construction workers and engineers. Often perceived as an unwanted gift from the Soviet Union to the new Soviet state of Poland, it served as a strategic move to establish the union’s stronghold in the region. Designed by the Russian architect Lev Vladimirovitch Rudniev, the building was a feat of constructed ideology.

The structure represents Polish national motifs researched by the architect during site visits to Polish cities, combining the Western concept of the skyscraper and Soviet monumental classicism. Despite being disliked by many, this proud beacon and illustration of power has continued to generate gifts after the fall of the Soviet Union, exchanged by and for the people, through the diverse programs it hosts.3

The Palace of Nations is an amalgamation of various gifts, commencing with the offering of Ariana Park as the location for the League of Nations by the city of Geneva. After an initial open call to choose a single architect, the committee decided to instead create a consortium of five architects from different nations in order to avoid a building bearing the mark of a specific national style.4 The building finished construction in 1938, on the brink of WWII. The Palace of Nations is also decorated by, and its interiors enriched with, gifts from member states.5 These gifts kept growing in number over time as the League of Nations evolved into the United Nations, and new members continued to offer gifts, from dances performed on special days of celebration to paintings and sculptures.

The original interior decoration and artworks are today being replaced by new gifts (by the likes of United Arab Emirates and Qatar, among others), which can be read as scenographic aides for overriding the outdated European colonial style of the 1930s still so evident in the building and illustrating contemporary geopolitical power relations. Further debates on the suitability of symbolism from the 1930s and political correctness are currently taking place at the United Nations today, with outstanding questions on how to return an unsuitable gift.

The Memorial House of the Bulgarian Communist Party is perched on Buzludzha Peak, nestled in the mountainous terrain of Bulgaria. Inaugurated in 1981, it served as a citizen-funded tribute to the Socialist movement in Bulgaria. Its architect, Georgi Stoilov, conceived the idea of creating a monument that transcends time by incorporating ancient and futuristic elements into its design. Work began in 1974 and more than 6,000 people, from engineers and artists to soldiers, contributed to the monument’s construction. The interior was decorated with mosaics detailing the history of the Bulgarian Communist Party. Stoilov himself suggested that the cost of its construction should not be carried by the state but be raised by voluntary contributions from the people. Commemorative stamps and “Buzludzha taxes” taken from people’s salaries paid for the building.

Since the country’s transition to democracy, the building has languished. The abandonment and decay of this once grand structure has been hastened by the original gift-givers: citizens who, in the aftermath of the collapse of socialism, have gradually stripped metal and other valuable materials from the building, including its solid copper ceiling.

The Protagonists

The Engineer advocates for the importance of connecting with citizens, grounding his arguments in socialist ideals. He positions himself as a defender of architecture as the fundamental social connector. During his presentation to the Freedoms, he accompanies his rhetoric with a tangible representation of his idealism. As he speaks, the Engineer assembles a model of his proposed gift: the last, and unrealized, pavilion of the former Yugoslavia at the 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal. This avant-garde architectural concept was overlooked in favor of a standardized design by committee, influenced by a resurgence of nationalism in the country in the late 1960s. The Engineer’s speech is crafted from the words of politically committed architects and engineers who played pivotal roles in the construction of buildings that served as theatres of power and that helped shape some of the most important political discussions of the twentieth century.

The Diplomat delivers his pitch while magically transitioning from the futurist theater of the PCF headquarters to the dim corridors of the Palace of Nations, which are adorned by gifts such as gilded frescoes and tapestries representing the “first world” and its riches. As he traverses these spaces, a recurring encounter with a violinist unfolds. She constructs a melodic score, and he finds himself compelled to interact with it. Passing her by, he adjusts and retunes her notes until she plays the tune designed by him. This melodic score draws from donations to the League of Nations by amateur composers during the Palace’s closure on the brink of World War II. Although these scores were never performed, they were deposited into the Palace’s archive. Comprising hymns and marches, they underscore the belief in what a national discourse requires: a hymn to announce it and a march to enter a war with—which also potentially signal its own demise. His words are drawn from political and diplomatic conundrums of expired political gifts and their functions, none of which ever disclose the actual form of the concepts they argue for. “Our gift will be immaterial,” he declares.

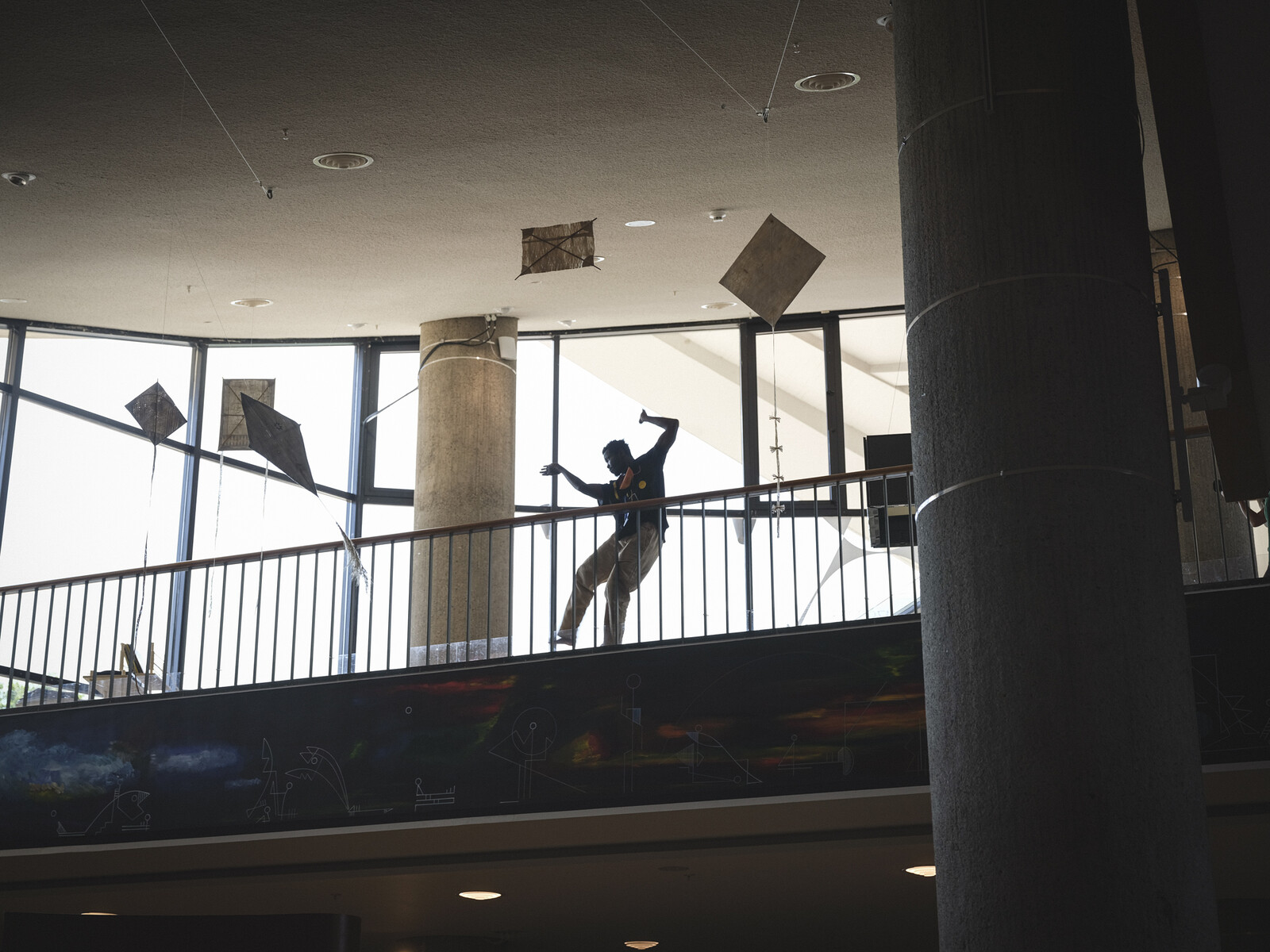

The Artist’s speech is an amalgamation of statements by various artists throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, capturing the ideological beliefs surrounding artworks created within the context of the political gifting of culture. His monologue seamlessly weaves together declarations associated with gifts made by the Futurists to Mussolini, Communists to the Communist Party, and contemporary artists to modern concepts of political and national authority. He picks up where the other two protagonists leave off ideologically, but swiftly veers away from constructive rhetorical propositions into chaos and destruction. As he vehemently commands center stage, his behavior aligns with the intensity of his address. Two dancers accompany him, translating his speech into a choreographed exercise incorporating elements from some of history’s most awkward relations to statecraft, including choreographies of state processions and poses drawn from artworks donated to political powers. The dancers’ choreography mirrors the Artist’s political statements and serves as a reclamation of movements previously held hostage by the ideological discourse of not-so-distant histories.

The Four Freedoms

On January 6, 1941, eleven months before the United States joined World War II, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered a speech to Congress that recognized the weariness of the nation, still recovering from the Great Depression and the aftermath of World War I. Anticipating the challenge of rallying public support for entering another war, his emphatic proclamation of the Four Freedoms—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—aimed to provide the nation with a compelling reason to back the administration’s decision.

Roosevelt’s speech underwent many drafts before the Four Freedoms were introduced.6 Despite the speech and the subsequent incorporation of the Four Freedoms into the Atlantic Charter, they initially failed to galvanize the nation for war.7 To promote these ideals, the US government encouraged artists to interpret the Four Freedoms, leading to various promotional items, such as posters and pamphlets. The American artist Norman Rockwell played a pivotal role in popularizing the Four Freedoms with his four interpretative oil paintings that toured the United States. His work was hailed by New Yorker magazine in 1945 as “received by the public with more enthusiasm, perhaps, than any other paintings in the history of American art.”8

In the film, the historical ready-made of the Four Freedoms is borrowed as the prism for judging culture as a candidate to heal a divided nation. Culture is, after all, resistant to wear and tear, and possibly the best candidate for the continuous loop of circulation required by the gift economy.9 Throughout the competition, the Freedoms become increasingly cryptic, paradoxical, and aggressive in their rhetoric. They deviate from their base characters and employ contradictions to push competitors beyond the boundaries of their principles.

As the spiritual leader of the competition, Freedom of Speech confidently proposes culture as the paramount gift. She maintains a nervous yet firm demeanor. Censorship does not exist for her. Her expressions are not only heard, but also seen, as she begins to critique the positions the gifts are presenting; positions she foresaw developing.

Believing in a higher power, Freedom of Worship considers herself to have greater authority, expecting her opinions to carry more weight. While unintentionally exclusionary, she desires the opportunity to question the gifts and their beliefs. Despite her faith in higher powers, she lacks a meaningful critique of political power.

Expressing a belief that everyone deserves an adequate standard of living, Freedom from Want struggles to understand the positions of the gifts. Slightly sulky, she emphasizes her position and value, expressing despair about humanity and holding a somewhat dismissive view of culture in general.

Appearing as the most lenient, Freedom from Fear patiently awaits the clarification of everyone’s positions, weighing the pros and cons before defending her own stance. Advocating for a gift free of aggression, she seeks contributions to stability and peace. Supporting borders and strict rules, she argues that these are essential for meeting the wider public’s wants and needs.

Epilogue

The gifting of culture has many times been instrumentalized for its symbolic meaning by agents of political and national power. When these political gifts facilitate and enhance the very powers they are gifted to, their meanings and paradoxes are revealed.

As the world enters a new era of nation-building, it becomes evident that the contemporary reproductive processes of power do not differ greatly from those in the time of our forebearers. This is why the complicity of the arts, architecture, and culture in the ongoing reproduction of political and national power is best observed through the rearview mirror of history.

As we sift through the unfulfilled promises in historical case studies of gifting culture, discernible patterns of resistance begin to surface. Initially slipping through our fingers like the debris of a brighter future, upon closer inspection these patterns outline a clear vision and materialize the illusion that they were meant to support and announce—precisely through their failure. Dead ideologies and states reveal more about their own conjuring mechanisms and tricks than their live counterparts.

If culture intends to assert itself as a critical corrective to the ongoing political and national spectacle, which continuously employs its services to enhance and justify its power, then we must amplify our potential agency as a trigger warning for the collapse of the illusions we collectively inhabit.

Marcel Mauss, The Gift, selected, annotated, and translated Jane I. Guyer (Chicago: Hau Books 2016), 8.

The “four freedoms”—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear— were originally coined in 1941 by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt to instill hope for a better future and foster unity among people.

For an in-depth analysis of the Palace of Culture and Science and its socio-political past and present, see Michal Murawski, The Palace Complex: A Stalinist Skyscraper, Capitalist Warsaw, and a City Transfixed (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019).

For a detailed analysis of the competition, see Ciro Luigi Anzivino and Ezio Godoli, Ginevra 1927: Il concorso peri l palazzo della societa’ delle nazioni e il caso le Corbusier (Florence: Modulo editrice, 1979).

Minutes of the second session of the works of the Jury (January 1926), 31-33, League of Nations’ Archives 32/49424/28594, cited in Ilda Delizia, Fabio Mangone, Architettura e Politica: Ginevra e la Società delle Nazioni, 1925-1929 (Rome: Officina Edizioni, 1992), 26.

Congressional Record, 1941, vol. 87, part I, cited in “The “Four Freedoms” Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Address to Congress January 6, 1941, Chapter 36,” in Philip Lee Ralph et al., World Civilizations (W. W. Norton Publishing, February 4, 1997). See ➝.

The Atlantic Charter was issued on August 14, 1941 and set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II.

Maureen Hart Hennessey and Anne Knutson, Norman Rockwell (Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 1999), 102.

In his aforementioned book, Mauss acknowledges the potential obligations linked to receiving a gift, as recipients are already aware of the psychological and social complexities associated with the act of giving, such as reciprocity. Mauss, The Gift, 8.

The Gift is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TUM in the Pinakothek der Moderne, and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan, within the context of the exhibition “The Gift: Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture” at the Architekturmuseum der TUM.