“I refuse to acknowledge time.” With these outlandish words, Mariah Carey begins her memoir, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, published in 2020. “It is a waste of time to be fixated on time,” declares the elusive chanteuse. “Life has made me find my own way to be in this world. Why ruin the journey by watching the clock and the ticking away of years?”1 Instead of counting the minutes and years, Mariah wants to live life “moment to moment.” Indeed, moments are one of her favorite things. See “Mariah Carey Needs a Moment” on YouTube; it’s a much-loved ninety-second supercut from her 2010–11 infomercials on the Home Shopping Network, in which she sells fashion, perfume, and jewelry items while enthusing about having a “diamond moment,” a “retro moment,” a “bandana moment,” a “genius moment,” a “dual moment,” a “fragrant moment,” a “skin-tight moment,” a “transitional summer moment,” a “full-on evening moment,” a “fun cute remix moment,” and so on.2

Mariah’s espousal of moments has inspired many, including Adam Farah-Saad (aka free.yard), a London-born and -based artist and dedicated Lamb whose work is often infused with MC’s language, lyrics, and iconography. (“Lambs” are what Mariah’s most devoted fans call themselves; collectively we are the “Lambily.”) Working across video, installation, and performance formats, Farah-Saad makes art with various things including poppers, friends, obsolete technologies like iPods and CDs, microdosing, wind chimes, personal memories and heartbreaks, fisheye lenses, cruising, lipsynching, and gourmet condiments. They have said that Mariah inspires them as an artist, “in terms of wanting to be really sincere and poetic in what I do and kind of not being afraid to even go a bit overboard with that.”3 Their solo exhibition at Camden Art Centre in 2021 was framed as a presentation of “peak momentations” from their life. The term “momentation,” they explain, refers to “a pronounced dwelling on the ephemeral—influenced by Mariah Carey’s queer disidentificatory theorisations of THE MOMENT.”4

The word “moment” comes from the Latin “momentum,” meaning “movement, motion, alteration, change.” It’s a shifty word: “in a moment” means very soon, to be “of the moment” is to be very current, to “live for the moment” is to act without concern for the future or the past. Moments are often temporal intensities that stand apart from the time that surrounds them; when we say “I need a moment” or “I’m having a moment,” it’s about puncturing the flow of things by carving out a pocket of time outside of regulated time. Moments are very different from minutes; they are decidedly transient, unquantifiable, indivisible, and non-accumulative. They’re brief but capacious; you can’t section them out or add them up in any normative way. For Mariah, living a life of moments means living “Christmas to Christmas, celebration to celebration, festive moment to festive moment,” while simply ignoring the rest, and always refusing to acknowledge the banality and brutality of standardized, accumulative, linear time. As she writes, “Often time can be bleak, dahling, so why choose to live in it?”5

A Fun Cute Remix Moment

Mariah’s refusal to acknowledge time has become a running joke in her online persona. When she tweeted about releasing an expanded edition of her 1997 Butterfly album to commemorate its twenty-fifth anniversary, she wrote, “Celebrating 25 … minutes … since the release of my favorite and probably most personal album.”6 Years, minutes; what’s the difference, really? In 2019, there was the social media trend #tenyearchallenge, which saw participants share two side-by-side photographs of themselves, ten years apart, for comparison. When MC joined, she tweeted the exact same photograph of herself—bikini-clad, smiling for the camera, and holding one of her cute Jack Russells—twice, side-by-side. Identifying the picture as one that had been “taken at some point prior to today,” she wrote, “I don’t get this 10 year challenge, time is not something I acknowledge [shrug emoji].”7

There are, of course, a number of other things that Mariah refuses to acknowledge. Jennifer Lopez, for one. It’s been more than twenty years since J-Lo’s career was launched with a track featuring a sample that was supposed to be on Mariah’s forthcoming single (in an intentional act of sabotage by Mariah’s vindictive ex-husband, the record executive Tommy Mottola). When people ask Mariah about J-Lo, she still says, “I don’t know her.” Similarly, when Eminem claimed publicly that he had hooked up with MC, she responded with her amazing dis track “Obsessed” (2009), in which she sings, “I don’t even know who you are.” When she was asked about her beef with Nicki Minaj, and whether or not Minaj was referencing Mariah in her lyrics, MC said, “I don’t know, I didn’t even know that she sang.”8 And while her memoir offers extensive detail on aspects of her personal life, there are several notable omissions, including her ex-fiancé James Packer (whom she reportedly sued for millions as an “inconvenience fee” when their engagement was called off). The refusal of acknowledgement is the ultimate shade, and she does the same thing with time. Time? she says, I don’t know her.

Mariah has never been particularly interested in short-term fashion trends, and, unlike other major pop stars with long careers, she hasn’t been through a series of era-defining chameleonic transformations. Watch her legendary MTV Cribs episode from 2002 and notice, when she gives us a tour of her closet (which is a whole wing of her palatial Manhattan penthouse), that the garments could belong to any time in her career, from the nineties up until today. When she shows us her shoe room, she explains, “The style that I favor would be a high stiletto, and the brand that I favor would be whoever’s gonna stick to that motif.”9 MC sticks to her motif. There have been a few looks that are tied to particular historical moments—like the emphatically early-2000s jeans with the cut-off waistband in the “Heartbreaker” (1999) video—but overall, her image has been remarkably consistent: high stilettos; that long, flowing hair all full of air; lots of leg; lots of cleavage; lots of sparkles and glitter.

She recounts in her memoir that a childhood inspiration for her particular brand of high-femme glamour came from her gay uncles—her “guncles,” as she calls them—Burt and Myron. “Burt was a schoolteacher and photographer, and Myron was, as he put it, a ‘stay-at-home wife,’” she writes. “Myron was a vision. He wore a perfectly coiffed beard and his hair was always blown out in cascading layers, which he would finish off with a shimmering frosting spray.” Sound like anyone? The guncles had a dog named Sparkle, and Burt would do photo shoots with the young Mariah, who loved to show off with exaggerated poses for the camera. “He fully supported and understood my propensity for extraness,” she recalls.10

This “propensity for extraness” situates Mariah in a lineage of high camp: a queer aesthetic sensibility that relishes exaggeration and fabulous detachment. Over the years, Mariah has leaned increasingly into her gay icon status. In her appearance as the headline act for LA Pride in the summer of 2023, she went all out: she had her muscle boys dance troupe (always), rainbows (of course), glitter (obviously), a giant, inflatable winged horse (gay Pegasus), a Grindr chat video as part of her visuals on the big screen (with “why you so obsessed with me?” showing up as her response on the gay dating app), and a huge, sparkling crown (she couldn’t keep it on her head and at one point she expressed a desire to break it apart and throw the pieces into the crowd, like Lindsay Lohan in Mean Girls, but “for all the queens of the land”). I was there (dying!), near a group of queens who were all wearing homemade “I don’t know her” tanks. I guess there is something very queer in refusing to acknowledge the hold of the blatantly obvious. (All-consuming cis-hetero-patriarchy? Never heard of it.) The world says, “This is what reality looks like, this is what desire looks like, this is what a life looks like,” and queers, against all odds, have said, “Actually, there’s more.”

Mariah Carey photographed by David Lachapelle on the back side of the album Rainbow, 1999. [ID: A photograph of Mariah Carey with blonde hair, in white briefs and a white tank, holding a red heart-shaped lollipop and standing against a white wall. She’s in the middle of a rainbow that has been spraypainted onto the wall and across her briefs.]

Writing in the 1960s, before MC was born, Susan Sontag pointed out that “many of the objects prized by Camp taste are old-fashioned, out-of-date, démodé.”11 (Sontag, who was described by Terry Castle as an “intellectual diva,” had her own iconic “I don’t know her” moment back in 1993, when she claimed to have never heard of Camille Paglia.12) It’s true that there is often something temporally “off” in camp aesthetics. A reason for this, according to Sontag, is that “the process of aging or deterioration provides the necessary detachment.”13 Think of the importance of Old Hollywood glamour in voguing and Black and Latinx ballroom culture, where the imagery and gestures of a bygone age can cross race, gender, and class boundaries, as well as temporal boundaries, to be reclaimed in the present through the timeless spirit of camp extravagance and glamour. Remember that the word “glamour” comes from the Scottish “gramarye,” relating to illusion, enchantment, sorcery, and spells. In Mariah’s case, the refusal to acknowledge time becomes the ultimate diva move, one that allows her image to travel across and away from chronological order, so that she is enduringly incandescent but never fully on the zeitgeist pulse—appearing always a little anachronistic.

Just as her image travels across time, refusing to sit within proper historical progression, MC’s songs also behave as time-traveling entities that can defy linearity. In 2018, her Lambs started the #justiceforglitter campaign on social media, to try to resuscitate and find “justice” for the album that had, seventeen years earlier, marked the biggest flop moment of her career. They succeeded, and managed to get Glitter to reach number one—for the first time—by streaming it incessantly on iTunes. Not long after Glitter’s belated arrival at number one, Mariah became the first artist in history to top the Billboard Hot 100 chart across four separate decades, thanks to “All I Want for Christmas Is You,” which seems to get more and more popular with every holiday season. In her memoir, she writes about how the 1994 track became the last number-one song of 2019 and the first number-one song of 2020, bringing her into her fourth decade at the top of the charts. (But really, she asks, “What is a decade again?”)14

Speaking of Christmas, MC’s signature embrace of the Christian holiday is also connected to her refusal to acknowledge the standardized advancement of time. When she appeared on her friend Naomi Campbell’s YouTube channel to celebrate the publication of The Meaning of Mariah Carey, Campbell began the conversation, as she usually does, by asking, “Where were you born and where did you grow up?” Mariah responds to the generic question by explaining, through giggles, “In the tradition of the Tooth Fairy and Santa Claus, I was never born—and here I am!”15 Rather than saying anything about her upbringing, she then starts talking about her love of Christmas and “festive moments.” While birthdays are cumulative and mark the passage of time, Christmas, for Mariah Carey at least, is outside of time: it doesn’t acknowledge the passing of years.

How old is Mariah Carey, actually? That’s a controversial question. One Lambily podcast has dedicated an entire episode to it.16 She recalls in her memoir that she cried on her eighteenth birthday because she still didn’t have a record deal, and she felt like her life would not begin until she had one. Appropriately, one Reddit user has commented in a forum on the age controversy: “She was born June 12th 1990.”17 That’s the date of the release of Mariah Carey, the debut album that delivered her into global stardom. When she did Carpool Karaoke in 2015, she said, “We’ll celebrate my eighteenth birthday with the fact that I’ve had eighteen number ones.”18 (“All I Want for Christmas” has gone number one since then, so that would make her nineteen now.) She also famously identifies as “eternally twelve” and has celebrated her “anniversary” (never say “birthday”) with a cake decorated with twelve candles.19

Adam Farah-Saad, EMOTIONS (1991), 2022, DVD tower rack, C-Type print, DVD case. [ID: A photograph of a DVD tower with red panels at the top and bottom, standing on a grey concrete floor, with the word EMOTIONS spelt out in caps across the spines of the DVD cases.]

MC’s refusal to acknowledge her age is, in part, a refusal to acknowledge the reality of aging. This obviously feeds into the patriarchal pressures of gendered ageism, but that doesn’t have to be the whole story. When Frida Kahlo changed her date of birth from 1907 to 1910, she made herself three years younger—but at the same time, she also made her origin coincide with the beginning of the Mexican Revolution, in a deliberate rewiring of time that affirmed her commitment to anti-imperialist and anti-colonial politics. In Mariah’s case, the fact that she looks much younger than she is (in a way that is only possible for the uber-wealthy) can be understood as both a product and a perpetuation of a youth-obsessed culture that equates older women with undesirability, monstrosity, irrelevance, and invisibility. Concurrently, though, there are also much more peculiar things going on in this woman’s estranged relationship with time. Really, she should have been included in the artist William Kentridge’s project The Refusal of Time (2012), which looked at how the imposition of normative, dominant time has been refused and resisted in multiple historical contexts.

Another mark of Mariah’s temporal estrangement can be found in her apparent hatred of the daytime. In her MTV Cribs episode, she says jokingly (or is she for real?), about the fish in her aquarium, “I had to get them changed to be nocturnal because they were on the opposite schedule as me.”20 She has struggled with sleep for most of her life, and has often lived out of sync with the waking world. Over time, she came to appreciate the night aesthetically (it is, after all, the time of dreams and glamour). In a video she recorded for Vogue magazine’s “Life in Looks” series, she responds to photos of herself from different moments of her long career, hating on the ones in which she appears in daylight. “It’s daytime, I should be sleeping, I don’t have time for this daytime shit,” she says. “Everything should be an evening event.”21

The thing about the evening event is that the lighting can be controlled. Daylight is light from an external source, one whose schedule and intensity is beyond anyone’s control. Mariah wants “victory over the sun” (to borrow from the outlandish title of a 1913 Russian futurist opera); she wants to control her own lighting and thereby create her own system of time. None of this externally dictated, default reality! MC proposes a life of reparative denialism; rather than being touched by the tedium of reality, she floats above it—like a butterfly, that airborne creature of metamorphosis, transience, and flight that has accompanied her image for decades.

I’m Ventilation

Mariah, in my mind, is related in strange ways to the air and the wind. She was named after the song “They Call the Wind Maria,” from the 1951 Broadway musical Paint Your Wagon. (Another jewel in her gay icon crown: being named after a show tune.) In the song, the wind is personified as an entity called Maria (pronounced as Mariah) who “blows the stars around and sends the clouds a-flying.” Maria Creek in Antarctica was also named after the song, because of the area’s strong winds. Mariah’s jazz number “The Wind” (1991) is about lost dreams and loved ones who “only fade into the wind,” where the wind is a painful reminder of irredeemable loss. But the wind is also connected to the ideal of nonattachment in MC’s cultivated persona, with her “I don’t know her” attitude of high-camp breeziness.

Literal breeziness has also been a defining feature of Mariah’s aesthetic; she even had a wind machine installed at home when she did a virtual appearance on The Daily Show during the 2020 Covid lockdowns, so that her hair would gently flutter throughout the interview. She writes in her memoir about her enduring obsession with wind-blown hair, “as evidenced by the wind machines employed in almost every photo shoot of me ever.” She recalls being enchanted, as a kid, by shampoo commercials on TV with “the magnificent, sunshine-filled, slow-motion-blowing-in-the-wind-while-running-barefoot-through-fields-of-flowers hair.” She once believed that the shampoo on the television could give her “the heavenly hair, blown by gusts of angels’ wings.” But while completing five hundred hours of beauty school training (which she did after graduating from high school), she came to understand that shampoo would never be enough. “It requires a lot of effort to achieve effortless hair,” she writes. “It takes professionals, products, and production, dahling—conditioners galore, diffusers, precision cuts, special combs, clip-ins, cameras, and, of course, wind machines.”22

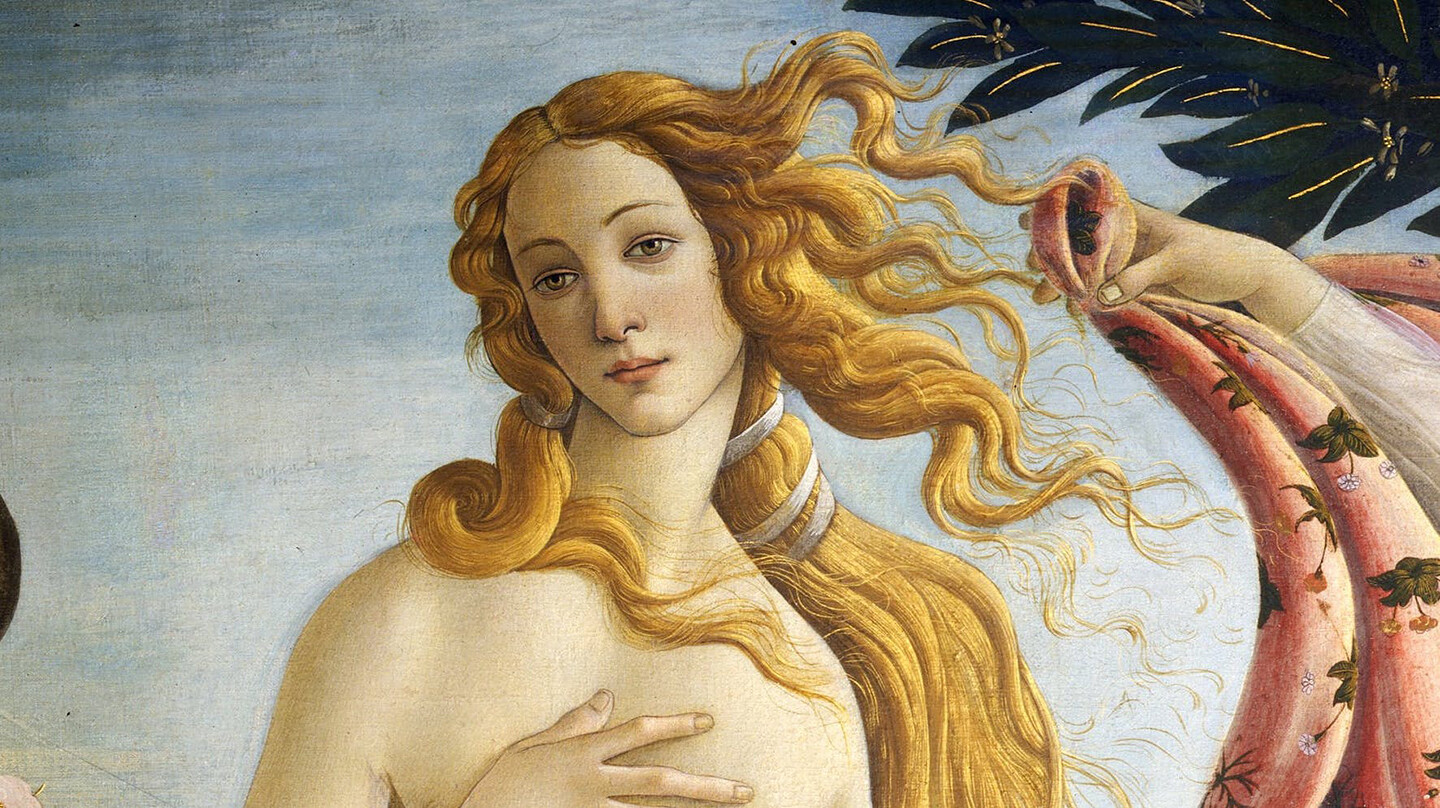

The German art historian and cultural theorist Aby Warburg would have been interested in MC’s wind machines. In his 1891 dissertation, he wrote about Sando Botticelli’s paintings Primavera (c. 1477–82) and The Birth of Venus (c. 1484–86), paying particular attention to the “imaginary breeze” that makes the wind-swept hair and billowing fabrics “flutter freely without apparent cause.”23 The philosopher and art historian George Didi-Huberman has described how Warburg shifted his focus “from the still beauty of Venus to the turbulent edges of her body—to hair, draperies, and breaths of air,” while developing his theory of the Nachleben or “afterlives” of images.24 Against the prevailing art-historical methodologies of his time, Warburg’s idea of Nachleben allowed him to look at images as manifestations of energies that move, irrationally, across time, defying sequential arrangements of causality.

As Didi-Huberman puts it, the wind “causes all that it touches to quiver or stir, to be moved or convulsed,” and “the passage of air also sends a quiver through time.”25 This is why Warburg was so attentive to the zones of instability and flight in Botticelli’s paintings; he wanted to see images released from the strict linearity of post-Enlightenment historicism. Wreaking havoc on proper periodization, he looked at Boticelli’s Venus as an illogically exuberant eruption of pagan antiquity into quattrocento Christianity, and beyond. According to Didi-Huberman, the figure in the wind “escapes gravity and the earthly condition; she becomes a semblance of the ancient gods, an airy creature of dreams and after-life, a revenant: an embodiment of Nachleben.”26 With these words, he could also be describing Mariah Carey, that decidedly detached “airy creature” who “escapes gravity and the earthly condition” while moving across historical eras and refusing to acknowledge time.

Intoxicated; Flying High

The breeziness surrounding MC’s image might also be understood as an incarnation of the most remarkable, otherworldly thing about her: that voice. When she appears amongst all that floating hair and rippling fabric, it’s like she’s also the source of the wind that she’s in (as she sings in “Obsessed,” while taunting Eminem, whom she also dresses up as in the video: “I’m ventilation”). Like her hair, her voice is soaring, multidirectional, and full of air. And just as her songs can reach across time (achieving a Warburgian Nachleben effect by becoming number ones outside of their historical contexts, decades after they were released), her voice is known for its impossible longevity, agility, and range. She jumps from silky whispers to deep belts and smokey growls to the highest notes of the whistle register, moving easily between the different parts of her massive five-octave vocal range—sometimes within what is ostensibly a single syllable.

I think I learned the word “incessantly” from Mariah’s “Heartbreaker” when I was fourteen, in 1999. Her lyrics are littered with words that you don’t usually hear in pop songs—words like “enmity,” “acquiescent,” “omnipresent,” “trepidation,” “incandescent,” “nonchalant,” “enraptured,” “emblazoned,” “denominator,” and many others. Mariah loves words, but she also loves to mess with them. When she sings, words begin to operate in excess of themselves. We hear the materiality of the sounds beyond their representational function. Language here is not simply a means to a communicative or productive end; it is also an embodied experience of sonic intensities—indivisible moments—where words forget their separateness and exceed their signifying attachments. This is what one writer has referred to as Mariah’s “evasive relationship to indexicality.”27 She turns words into dreamy, indulgent, asignifying hums. She stretches her syllables out into luscious, languishing occasions—pulsating the language away from its semantic designations.

The technical term for this kind of singing is “melisma.” While syllabic singing is tied to the regular tempo of the syllable, where each syllable gets one note, the melismatic voice says, I refuse to acknowledge the time that is set by the syllables—and instead moves successively through multiple notes within a single syllable. MC’s melismatic singing style developed through her influences from Black gospel traditions as well as her opera lineage. (Her mother is a retired opera singer.) Her breakout single “Vision of Love” (1990) is often credited with bringing elaborate melisma into mainstream pop music. There are some earlier instances of melismatic singing in pop, but it really went big in the nineties with Mariah and Whitney Houston, and it has been a defining feature of Mariah’s sound over the decades since.

As words are pulled away from their syllabic structures, melisma marks a propensity for extraness that opens up distended comprehension. There may be a loss of indexical meaning, but as we hear the words differently, they might also start to accrue other possible meanings. In an essay about dependency, food, and Theodor Adorno’s warnings against “culinary listening,” the artist and theorist of disability aesthetics Amalle Dublon writes about Mariah’s “Honey” (1997) (a song in which MC declares, seductively, “Oh baby I’ve got a dependency”) and the ways in which her vocals might help us to understand need through its entanglements with pleasure, invention, and enjoyment. Dublon:

At the end of “Honey,” the word honey, ornamented by Carey’s vocal runs, devolves, via agonizingly horny turns, into the phrase I need. At least, that’s what it sounds like. We’ve all made up pop lyrics from blurry phonemes where “culinary” singing distorts and distends meaning, necessitating equally hungry listening. Just as with eating, here, enjoyment and need become inseparably entangled.28

While exceeding the semantic, melismatic singing also turns time into a highly elastic material. Just listen to “Fantasy (Sweet Dub Mix),” a sublime “Fantasy” remix featuring re-recorded vocals, which Mariah made with David Morales in 1995. Over eight minutes and fourteen seconds, her voice floats above and away from regimented, earthly time. Halfway through the track, things suddenly sllllloowww rrrriiiightt ddoooown with an extended instrumental that plunges us into disorienting temporal dilation, until the vocals kick back in and time begins to speed towards a climactic release. Mariah sings like a drunken angel, and language becomes para-linguistic: words fly off into ethereal whistles and moans, lyrics become orgasmic murmurations that defy transcription, and syllables are stretched out into amorphous abstractions, unhinged from regulated time.

Losing my mind listening to this track through headphones while riding my bike around Berlin’s Tempelhofer Feld, I was reminded of a moment in Mariah’s MTV Cribs episode when she’s showing us around her apartment and she suddenly wants to lie down on the chaise lounge that she has permanently installed in the middle of her kitchen, just because. “I have a rule against sitting up straight,” she says, luxuriously. “I prefer to lounge.”29 Sometimes in live concerts, she will have her muscle boy dancers carry her around on a chaise lounge (she’s an iconically bad dancer)—and she applies the same principle to her voice: she stretches it out, reclines, elongates, takes and makes her own time, disregarding the reality that has been dictated by the surrounding conditions. There is a lesson here: lie down in the park, in the middle of the apartment tour, in the middle of the kitchen, in the middle of the performance, elongate the syllable in the middle of a word, stretch out the middle of the song, practice slowness and horizontality, extend the Moment, luxuriate in “queer extensities,” refuse the endless forward march, “cease to be soldiers in the army of the upright,” as Virginia Woolf put it.30

The artist, musician, and proud stutterer JJJJJerome Ellis has theorized melisma as “sonic investigation into what lies beyond, within, beside the syllable.”31 Studying the relationships between dysfluent speech, Blackness, and the nonnormative temporalities of melismatic song (especially in gospel music), Ellis writes about the way that melisma can split the syllable open and make a clearing, a space for Black gathering, by stealing time away from the dominant orders of extractive white universalism—and by interrupting the brutally ableist temporalities of hyperproductivity, efficiency, and rationalization. In his 2021 artist book The Clearing and his 2021 album of the same name, Ellis meditates on Aretha Franklin’s elaborately melismatic rendering of “Amazing Grace” as recorded at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles in 1972.32 “She takes a hymn she knows most people in the church will know and makes clearings all through it,” writes Ellis. “She dehisces the hymn, makes it porous, that all may gather therein. She reminds us that a syllable is an opportunity for tarrying, for dilation, for divergence, for abundance.”33

One Is Not Born, But Rather Becomes, a Butterfly

In a chapter of her memoir that is lovingly titled “Divas,” Mariah writes about Aretha Franklin as “my idol,” “the one who I thought was the one,” and “my high bar and North Star.” She recalls proudly that she was the only singer Franklin did a duet with on Divas Live in 1998, and that Franklin later sang some of Mariah’s songs, including “Touch My Body” when she was on tour (“she ad-libbed all the frisky bits”). One of the ways that Franklin inspired her, Mariah writes, was that she “wouldn’t let one genre confine or define her.”34 The Queen of Soul moved across and between gospel, jazz, R&B, and pop, at a time when this was no easy feat—and Mariah also had to fight hard against music industry dictates in order not to be confined by the “pop ballad” and “adult contemporary” genres that her record label wanted her to stick to in the early years of her career.

While she won’t acknowledge her age or count her birthdays (“I was never born—and here I am”), MC will acknowledge her sun sign: she’s an Aries—just like Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross, Chaka Khan, and Billie Holiday, as she notes in her memoir. And it was in true Aries style that she first burst into fame—like a charging ram, with no patience or boundaries—with her debut album Mariah Carey in 1990. Featuring the songs that she had written for the demo album she made when she was eighteen, Mariah Carey went platinum nine times in the US and sold fifteen million copies worldwide. Her first five singles became number ones—no other artist has ever achieved this—and she had number ones in every single year of the nineties.

Mariah Carey meme. [ID: On the left side of the image there is an enormous storm with a dog’s face. On the right side, there is an aerial view of a suburban sprawl, with text in white that identifies it as “Society in 1990.” Within the storm that is fast approaching this unsuspecting society is the cover of Mariah Carey’s self-titled debut album from 1990.]

During this first decade, Mariah was married to Tommy Mottola, who was the head of her record label, Sony. She was eighteen when they met; he was forty-nine. In The Meaning of Mariah Carey, she describes her relationship with him in meteorological terms: he was “like a fog,” “dense and oppressive,” “an entire atmosphere,” and “like humidity—inescapable.”35 He kept her under surveillance in her own home and prevented her from leaving without his permission. She recalls hiding in her shoe collection with her friend and collaborator Da Brat (a nineteen-year-old rapper and fellow Aries) to get away from the motion-sensitive security cameras that Mottola had installed throughout the rest of the property, monitoring her every move.

MC had spoken publicly in the past about how obsessively controlling Mottola was as a husband and manager. In the memoir, she addresses the extent to which his abusiveness was bound up with anti-Black racism. “The Black part of myself caused him confusion,” she writes. “From the moment Tommy signed me, he tried to wash the ‘urban’ (translation: Black) off of me … Just as he did with my appearance, Tommy smoothed out the songs for Sony, trying to make them more general, more ‘universal,’ more ambiguous. I always felt like he wanted to convert me into what he understood—a ‘mainstream’ (meaning white) artist.”36

One realm in which Mariah was able to claim a more autonomous space to experiment musically—and reinvent herself on her own terms—was in the remixes. Rather than simply recycling from the original track, her remixes were often complete rerecordings. She writes about doing dance remixes—“for the club kids (who have always given me life)”—with DJ/producer David Morales, who came out of New York’s queer Black and Latinx club scenes in the 1980s. When she worked with Morales on a mix, they would usually record new vocals, with MC singing the “same” song in a new key, with a redefined tempo, a different melody, and altered lyrics. “We often worked late at night, when I could steal a moment for myself,” she recalls. “David would come to the studio, and I’d tell him he could do whatever he wanted with the song. I’d have a couple splashes of wine, and we would just go wherever the spirit took us—which were almost always high-energy dance tracks with big, brand-new vocals.”37

In the mid-nineties, MC also approached Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs, head of Bad Boy Records, to be the producing partner on a “Fantasy” remix that she was fantasizing about. She told Puffy that her dream was to have Ol’ Dirty Bastard from the Wu-Tang Clan rap on it. She recalls that her own record label executives—whom she refers to as “the suits at the ‘corporate morgue’”—tried to stop her. “They didn’t understand how diverse my fans were, nor did they understand the global impact of the Wu-Tang Clan,” she writes. But she and Puffy managed to pull it off. Predictably, Mariah’s racist husband (who, she recalls, had commented that “Puffy will be shining my shoes in two years”) hated O.D.B.’s rap when he heard it: “‘The fuck is that?’ he blurted. ‘I can do that. Get the fuck outta here with that.’” But Mariah understood immediately that O.D.B.’s verses were magic (“all his crazy ad-libs sent me into euphoric giggles”)—and the “Fantasy” remix went down in history as the song that ushered in a whole new era of cross-genre collaborations between mainstream pop and hip-hop artists.38

When Mariah released her first greatest-hits album, #1’s, in 1998, she chose to include the Bad Boy Records “Fantasy” remix featuring O.D.B. instead of the original single. That’s the thing about “Fantasy”; the remix is more iconic than the original. But of course, if you refuse to acknowledge time, the hierarchical distinction between the “primary” original and the “secondary” derivative doesn’t have to hold up. “In order to make the label happy,” Mariah writes of this time in her life, “I had to deliver several versions of a single, including one that was up-tempo and simple, scrubbed of all ad-libs and ‘urban inflections.’”39 This scrubbed-up “version” would be the one that was called the “original,” but it might make more sense to say that the remixes constitute the primary form—because that’s where MC could be herself and make the music she wanted to be making—while the originals were simply the “versions” that she had to get out of the way in order to appease her label/husband.

White-supremacist culture can try, perversely, to insist that there is a true, essential, clean, untainted, neutral, nonracialized, and universal original that comes first, while the remix is a secondary and derivative deviation with optional, added elaboration for a subcategory of listeners. But Mariah comes to hip-hop as an art form of nonlinear gathering and relational contamination that renders the value of the pure, fixed, and singular original defunct. The history of whiteness in the US is a history of violently repudiating the mix, with the “one-drop rule” and anti-miscegenation laws being based on the fear of contamination (Mariah recounts in her memoir that her white, southern mother was completely cut off from her family after she married Mariah’s Black father). The history of hip-hop, meanwhile, is a history of the mix and all that can happen in the combining, scratching, and clashing of different sounds. Sampling and remixing practices mean that songs become expansive ecologies of references and relations, and sounds are always polyphonic and multi-temporal. Even the biggest solo stars will always be accompanied by other voices; in the words of poet, dancer, and jazz archivist Harmony Holiday, hip-hop is a “friendship-based art form.”40

Take, for instance, “Genius of Love.” Mariah’s “Fantasy” sampled both melody and lyrics (including the line “There’s no beginning and there is no end”) from this 1981 dance hit by the Tom Tom Club, a new wave band formed by two members of Talking Heads. But the “original” track was already crowded with a plurality of genres, influences, and collaborations. It was produced by Jamaican audio engineer Steven Stanley at Compass Point Studios in The Bahamas; Uziah “Sticky” Thompson—who was working with Grace Jones in the studio next door—added percussion; Monte Brown—a guitarist with Bahamian funk band T-Connection—added a rhythm part; and reggae and dub producers Sly and Robbie came in with handclaps on the backbeats. The lyrics feature tributes to numerous soul, funk, and reggae artists including Sly and Robbie, Smokey Robinson, Bob Marley, and James Brown—and the line about “a hippie-the-hip and a hippie-the-hop” echoes the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” (1979), one of the first rap singles to be played on the radio, with lyrics that brought the new term “hip-hop” to a wider audience.

A product of hybridized gathering at the outset, “Genius of Love” then proliferated through music history as one of the most popular samples in hip-hop throughout the 1980s and beyond. Dr. Jeckyll & Mr. Hyde’s “Genius Rap” came out in 1981; Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five’s “It’s Nasty (Genius of Love)” came out the following year, and the track was subsequently borrowed from or interpolated by Public Enemy, Ice Cube, Busta Rhymes and Erykah Badu, Warren G, 50 Cent, Snoop Dogg, and countless others, including, of course, Mariah Carey and Ol’ Dirty Bastard. There is a tradition, throughout, to play with the song’s opening lines: “Whatcha gonna do when you get out of jail? I’m gonna have some fun!” When 2Pac does it, he sings, “Whatcha gonna do when you get out of jail? I’m gonna buy me a gun.” When Biz Markie sings it, the answer becomes: “I’m gonna have some sex!” In Mariah’s iconic version, things get meta: “Whatcha gonna do when you get out of jail? I’m gonna do a remix.”

It’s fitting, for an artist who declares a refusal to acknowledge time, that the remix has been such an important part of Mariah’s approach to making music. To remix is to mess with linearity; to break it up and rearrange its parts; to layer, bend, and splinter off, reshuffling and redirecting the order of things. This is one of the ideas folded into the artist John Akomfrah’s Afrofuturist film essay The Last Angel of History (which came out in 1995, the same year as Mariah’s “Fantasy”). The film’s “data thief” is a time-travelling scavenger who steals remnants from the histories and ruins of Black culture to forge new relations across time. Music critic Greg Tate speaks in the film about sampling as “a way of collapsing all eras of Black music” and “being able to freely reference and cross-reference, you know, all those areas of sound and all those previous generations of creators, kind of simultaneously.” Drum and bass musician Goldie (whose debut studio album Timeless also came out in 1995) suggests something similar in The Last Angel of History when he remarks that “because of technology, being able to take from any of those eras, time is irrelevant.”

The Ensemble

You know, with the right bug repellent, hair and make-up, and ensemble, I could be outdoorsy … In a photo.

—Mariah Carey

In 1997, MC released her sixth studio album, Butterfly. It was her most overtly hip-hop project to date (featuring collaborations with Puff Daddy, Q-Tip, Missy Elliott, Trackmasters, members of Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Da Brat, and others), and the first album that she released following her long-overdue split from Mottola. She writes in her memoir that the lyrics from the titular track—“spread your wings and prepare to fly, for you have become a butterfly”—were based on what she fantasized Mottola would say to her as she freed herself from him.41

In the years since, Mariah has played recurringly with the idea of becoming/revealing her “true” self. She declared the theme of self-emancipation once again with her album The Emancipation of Mimi (2005), using one of her personal nicknames in the title. With Memoirs of an Imperfect Angel (2009), she framed the album as a confessional memoir; for the title of her 2014 album Me. I Am Mariah … The Elusive Chanteuse, she combined the caption she had written on a childhood self-portrait (which was reproduced on the back cover of the album) with a new nickname that she had come to embrace, once again declaring this is me. When she named her memoir The Meaning of Mariah Carey, she continued to play with the promise of staging a grand reveal of her “real” self.

All these layers of unveiling—and yet, Mariah’s appeal has never been about authenticity or relatability. I mean, let’s be honest; she’s the antithesis of down-to-earth. The cosmology of Mariah Carey is one of sweet, sweet fantasy: this is a world of rainbows and puppies; glitter and euphoric giggles; butterflies and candy bling; daydreaming and swimming in stilettos; honey and bubble baths; wearing a silk negligee while running free with a stampede of horses, hair blowing in the wind forever. There are emotions (as the title of, and first single from, her second album made explicit), but they are usually de-particularized and untethered from the real. “I don’t know if it’s real,” she sings in “Emotions.” “But I like the way I feel inside … You’ve got me feeling emotions.” With her voice soaring “higher than the heavens above,” this is not about feeling something in particular, it’s about feeling as such.

Ultimately, there will be no final emancipation, no final emergence from the chrysalis, no final decoding of “the meaning of Mariah Carey,” because Mariah Carey remains always at a remove in her OTT, un-pin-down-able many-ness. This quality of lofty multiplicity that won’t be contained or stabilized is something that can be felt in her melismatic vocals. Within a single vowel, she can change the note as many times as she changes her outfit—or, to use the word she prefers, ensemble—on her MTV cribs episode. In “My All,” for instance, she sings “I-I-I-I-I give my all”—forming five syllables (or more, depending on the rendition) out of a single syllable, one letter, the “I,” the first person singular, which is now made into an ensemble—a plurality that spills out from itself. It also spills (just like honey) out from the containers of globally imposed linearity, with its extractive logic that divides time up into dry, rationalized units. Her voice seems to know that to refuse to acknowledge time is impossible, ludicrous, and absolutely essential for all of us—because in the refusal, there is an affirmation of the otherwise.

Mariah Carey becoming an ensemble in the music video for “Loverboy,” 2001. [ID: Mariah Carey in a bikini top, with blonde, wind-blown hair, surrounded by four blurry duplications of her own image.]

In an essay about his decades-long love for the elusive chanteuse, writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen looks at how Mariah performs persona rather than personhood—and how her virtuosic skill can function as a means for deflecting from the particularities of individual identity. “Rather than a testimony to Mariah’s emotions, or an appeal to ours, the heart-ached lyrics to ‘If It’s Over’ (1992), ‘Without You’ (1993), or ‘My All’ (1997) are dramatic because they must be in order to meet her voice,” writes Madsen. “Her ballads are never actually sad. They are impressive, not expressive, and as a result there’s not much for us to identify with.”42 This is actually something that Mariah’s harshest critics complained about in the early years of her career. In a two-star review of Emotions for Rolling Stone in 1991, for instance, one music journalist bemoaned, “Her range is so superhuman that each excessive note erodes the believability of the lyric she is singing.”43 To this I would say: if you’re looking for believability, Mariah Carey is probably going to disappoint. But if you’re partial to an unbelievable “propensity for extraness,” and you’re on board with the capacity to exceed the plausible, she might have something for you.

This playlist was compiled by the artist Adam Farah-Saad to accompany Amelia Groom’s article “There’s No Beginning and There Is No End: Mariah Carey and the Refusal of Time.”

Mariah Carey and Michaela Angela Davis, preface to The Meaning of Mariah Carey (Andy Cohen Books, 2020).

See →.

See →.

See →.

Carey and Davis, preface to The Meaning of Mariah Carey.

Mariah Carey (@MariahCarey), Twitter, September 14, 2022 11:38 a.m. →.

Mariah Carey (@MariahCarey), Twitter, January 16, 2019, 5:03 p.m. →.

See →.

See →.

Carey and Davis, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, 19.

Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’” Against Interpretation and Other Essays (Noonday Press, 1966), 285.

Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’” 285.

Carey and Davis, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, 335.

See →.

“Mariah Carey Eternally 12: The Conspiracy,” April 15, 2021, in The Obsessed Podcast, 41:32 →.

See →.

See →.

Mariah Carey (@mariahcarey), Instagram photo, March 28, 2020 →.

See →.

See →.

Carey and Davis, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, 76–77.

Cited in Georges Didi-Huberman, “The Imaginary Breeze: Remarks on the Air of the Quattrocento,” Journal of Visual Culture 2 no. 3 (2003): 277.

Didi-Huberman, “The Imaginary Breeze,” 277.

Didi-Huberman, “The Imaginary Breeze,” 277.

Didi-Huberman, “The Imaginary Breeze,” 286.

Kristian Vistrup Madsen, “The Charms on Her Bracelet,” The White Review online, February 2021 →.

Amalle Dublon, “Mariah Carey Remix, 25th Anniversary Edition (feat. Theodor Adorno and Lauren Berlant),” Art in America online, November 9, 2022 →.

See →.

See →.

Ellis, “The Clearing.”

Carey and Davis, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, 303.

Carey and Davis, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, 97.

Carey and Davis, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, 147–48.

Carey and Davis, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, 170.

Carey and Davis, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, 161–62.

Carey and Davis, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, 170.

“Fred Moten & Harmony Holiday on the Sounds of Friendship,” Frieze online, December 17, 2020 →.

Carey and Davis, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, 180.

Madsen, “The Charms on her Bracelet.”

Rob Tannenbaum, “Emotions,” album review, Rolling Stone, November 14, 1991 →.

This text began as a short talk for the “Public Sewer (Keep your mind in the gutter™)” event series at the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam, for which speakers are asked to address a submerged niche interest in the gutters of their creative practice. The author wishes to thank the organizers Aidan Wall and Artun Alaska Arasli for the invitation, as well as the audience members who offered helpful questions and responses. Thanks also go to Amalle Dublon, M. Ty, Elvia Wilk, and Vivian Ziherl who helped in developing the text in various ways—and to the participants at the Warman School Summer Residency who shared valuable insights and feedback.