Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

March 28, 2024 – Review

Angela Tiatia’s “The Dark Current”

Stephanie Bailey

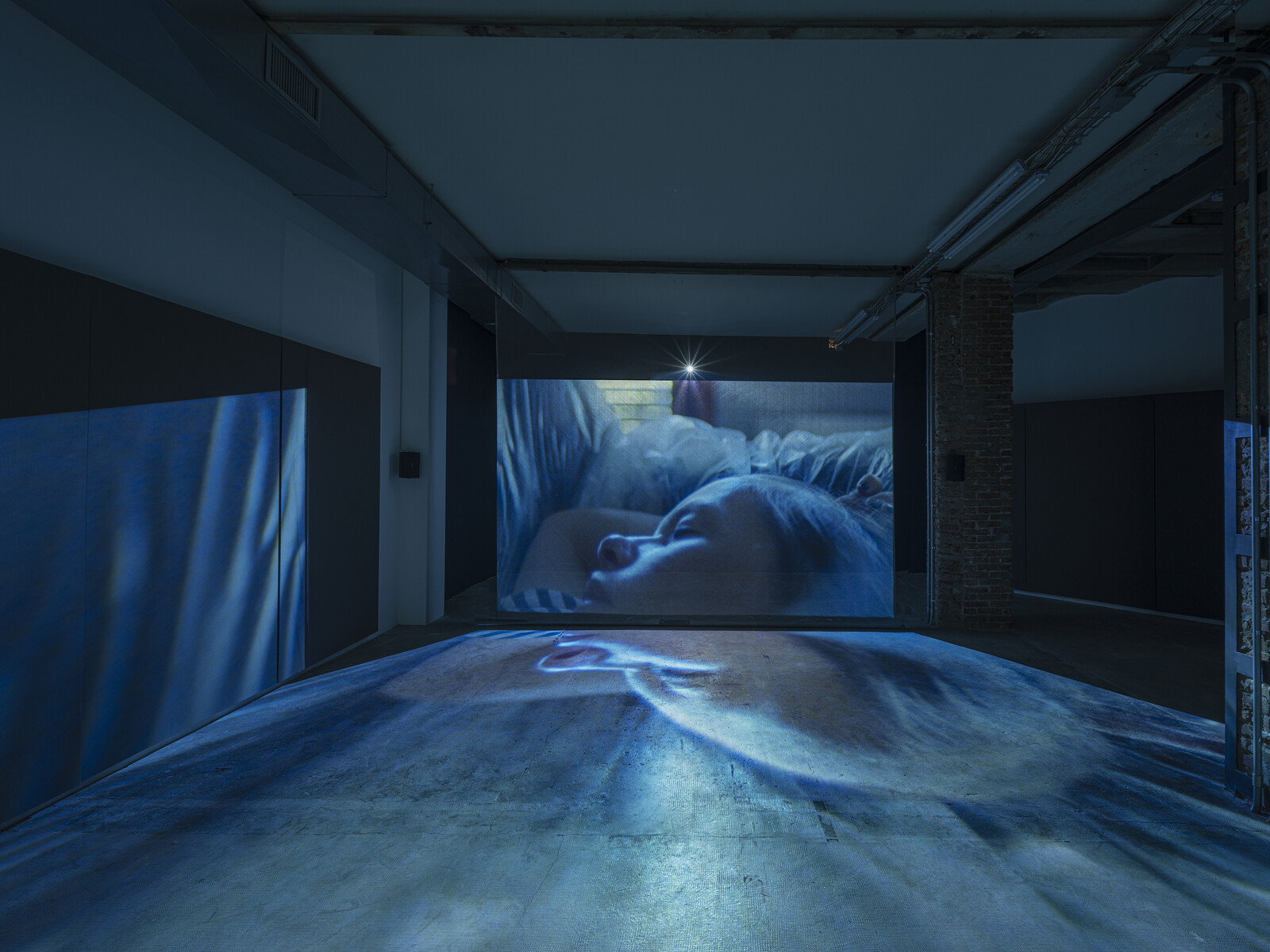

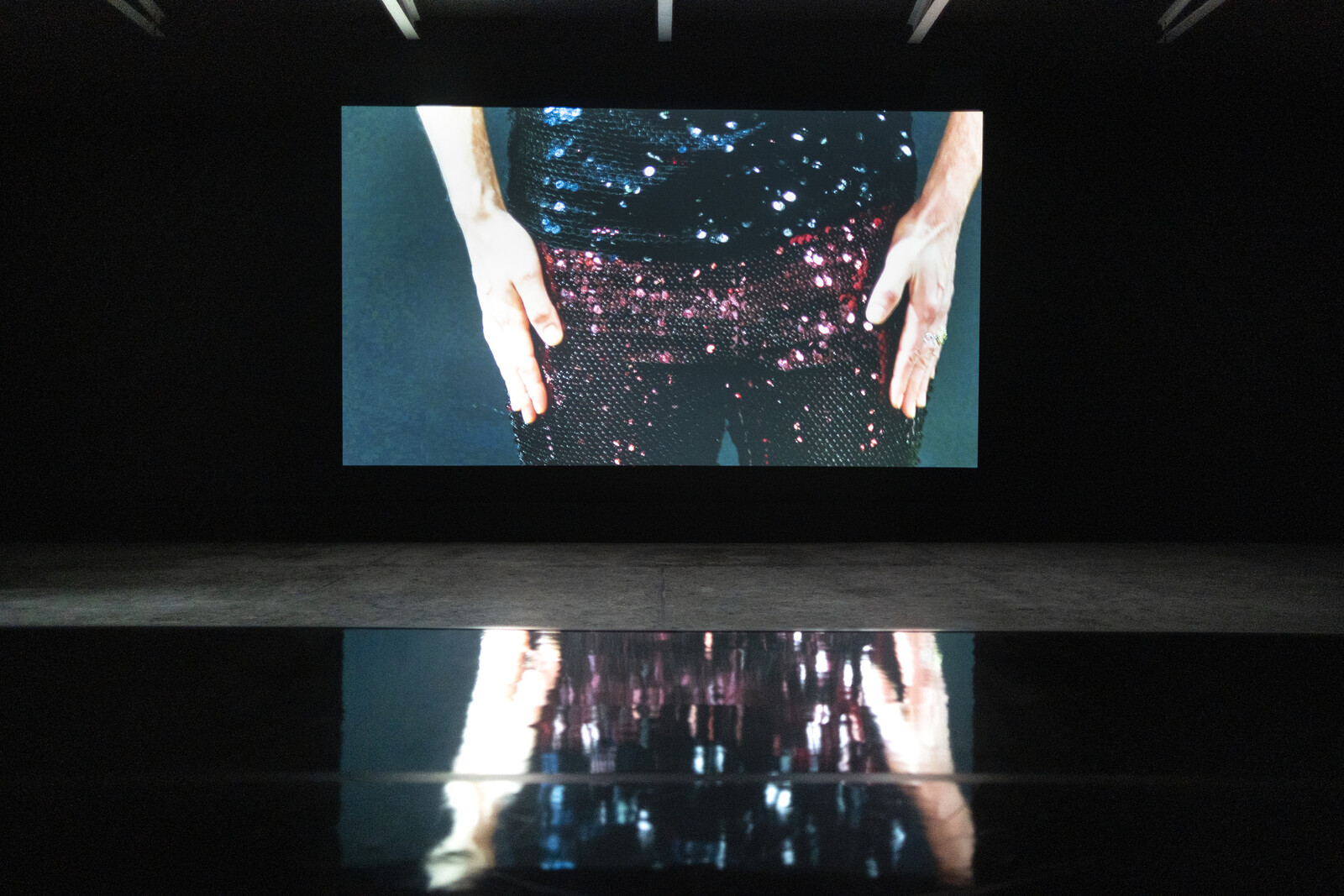

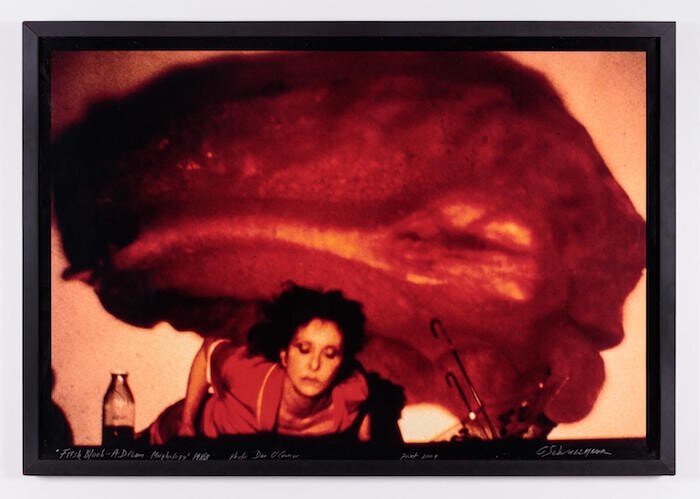

Angela Tiatia’s single-channel moving image work The Dark Current (2023), projected onto one wall in a darkened room, opens with a body-as-landscape. A cropped, lateral view of a floral appliqued fuchsia dress follows the concave slope from breast to waist as dark waters lap in the background, like an island. The camera slowly pans to the side, following the cleavage’s arc until it reaches the face of a woman with a pearl perched delicately at one tear duct. The lens then rises over her to gaze down at her from above. Lying in black water atop a magenta panel, her arms move slowly to create a frame of rippling waves around her.

The pearl is a portal to The Pearl (2022), an earlier immersive video installation not shown here, which was commissioned for “Matisse Alive” at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (2021–22), reflecting on Henri Matisse’s travels to the Pacific Islands through juxtapositions of his works with tivaevae quilts and commissions by artists Nina Chanel Abney, Sally Smart, Robin White, and Tiatia. Departing from Venus in a Shell (1930), a bronze sculpture that Matisse made the year he visited Tahiti, Tiatia composed The Pearl as a digital tapa, …

March 21, 2024 – Review

noé olivas’s “Gilded Dreams”

Suzanne Hudson

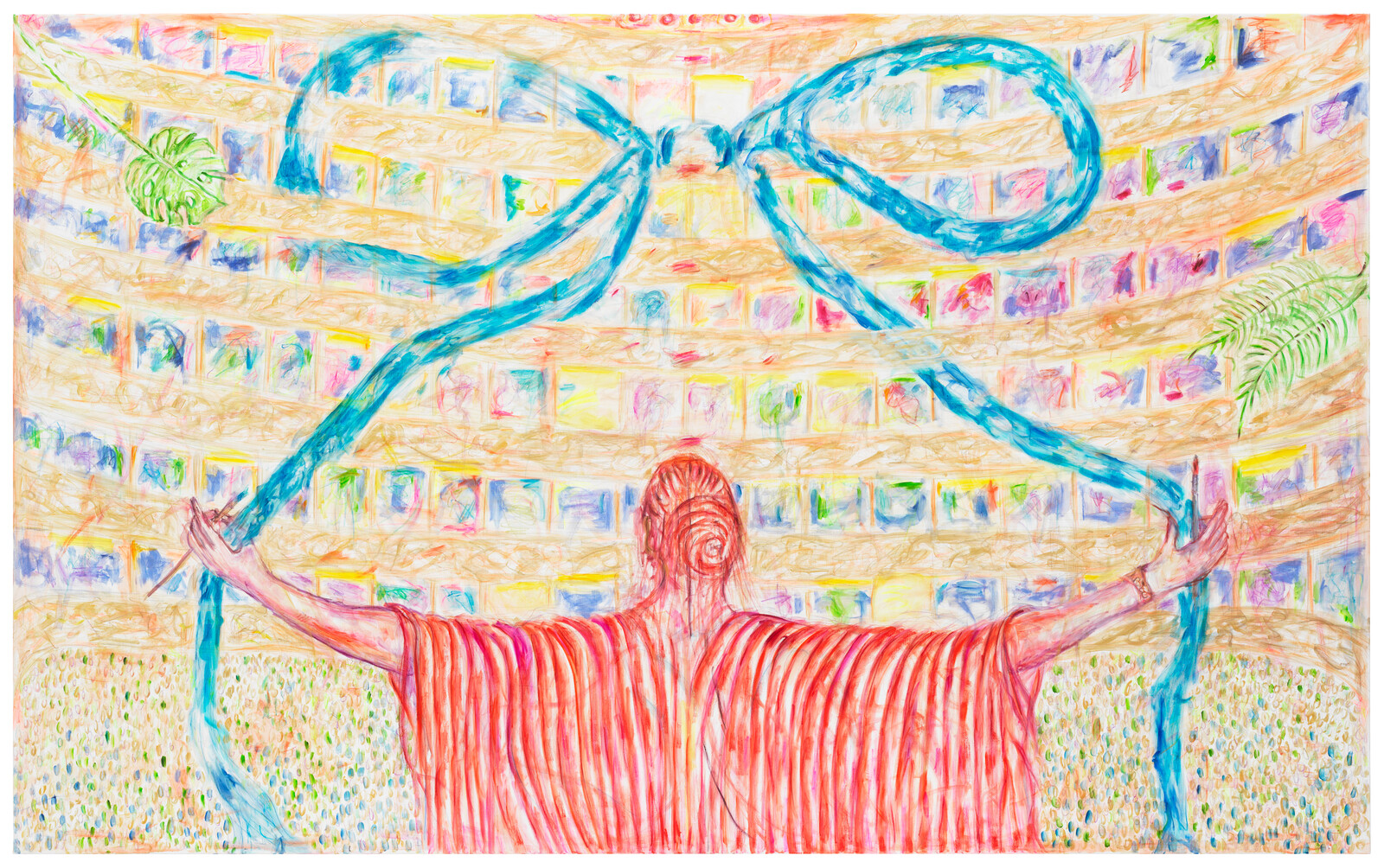

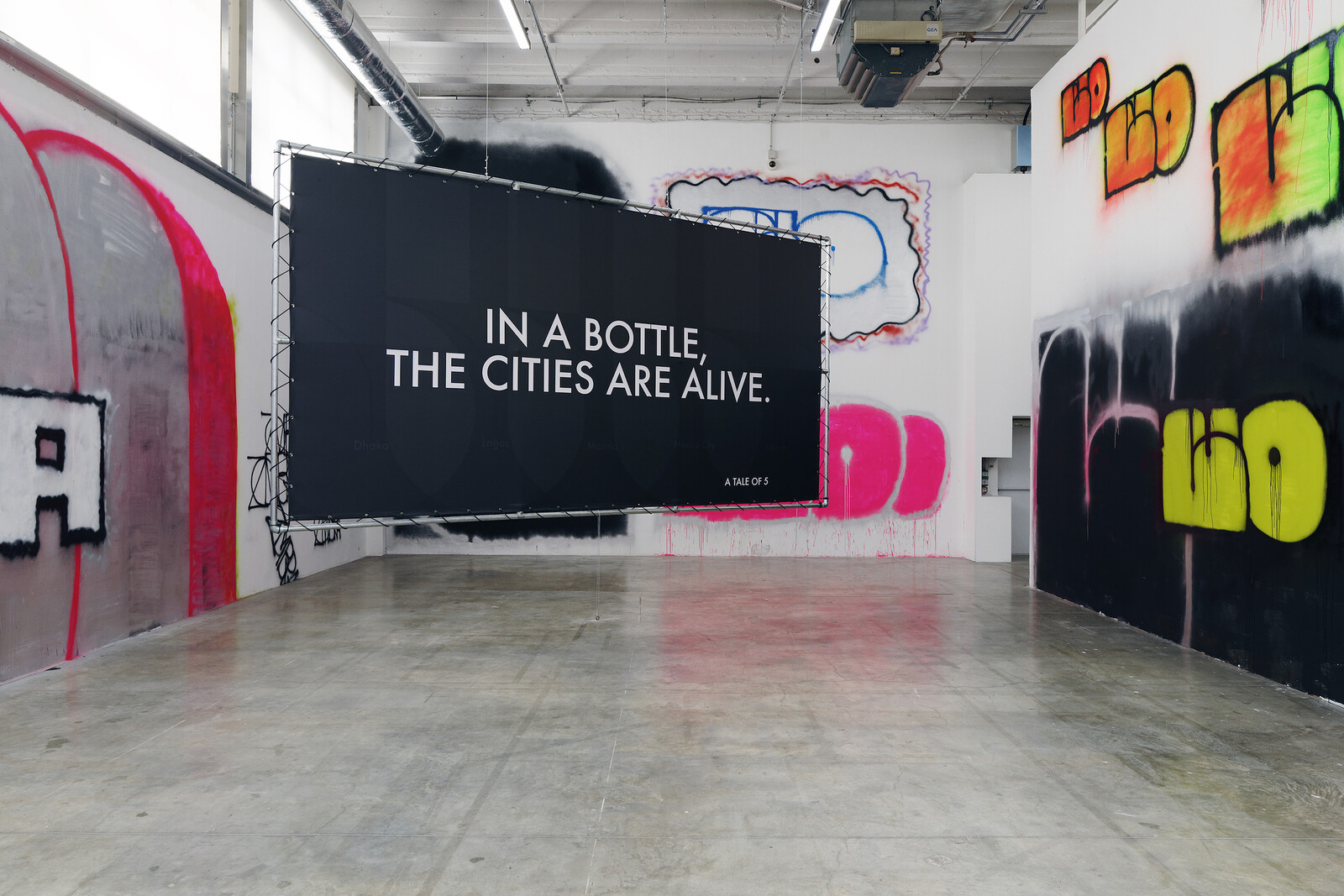

With Patrisse Cullors and alexandre ali reza dorriz, noé olivas is a co-founder of the Crenshaw Dairy Mart, a collective and gallery with adjacent studio space dedicated, in their words, “to shifting the trauma-induced conditions of poverty and economic injustice, bridging cultural work and advocacy, and investigating ancestries through the lens of Inglewood and its community.” For a not-inconsequential time after its March 2020 opening and near-simultaneous pandemic-shuttering, it also served as the locus of art supply and food distribution—the latter in collaboration with Lauren Halsey’s Summaeverythang—extending the site’s history as a functioning convenience store. That it sits right under the flight path for Los Angeles International Airport provoked reckoning, from the first, with its imagined audiences alongside those more proximate. The group’s exhibition made in response to the virus, “CARE NOT CAGES: Processing a Pandemic,” lived online; olivas’s mural spelling out the same sentiment blanketed the parking lot as a horizontal billboard visible from above, coming into focus on a jet’s descent. The words function as an incantation but also an indictment, denouncing racial capitalism and the twinning of epidemiological and carceral disaster that the disease exacerbated but did not need to produce.

“Gilded Dreams” follows this initial mandate, …

March 20, 2024 – Review

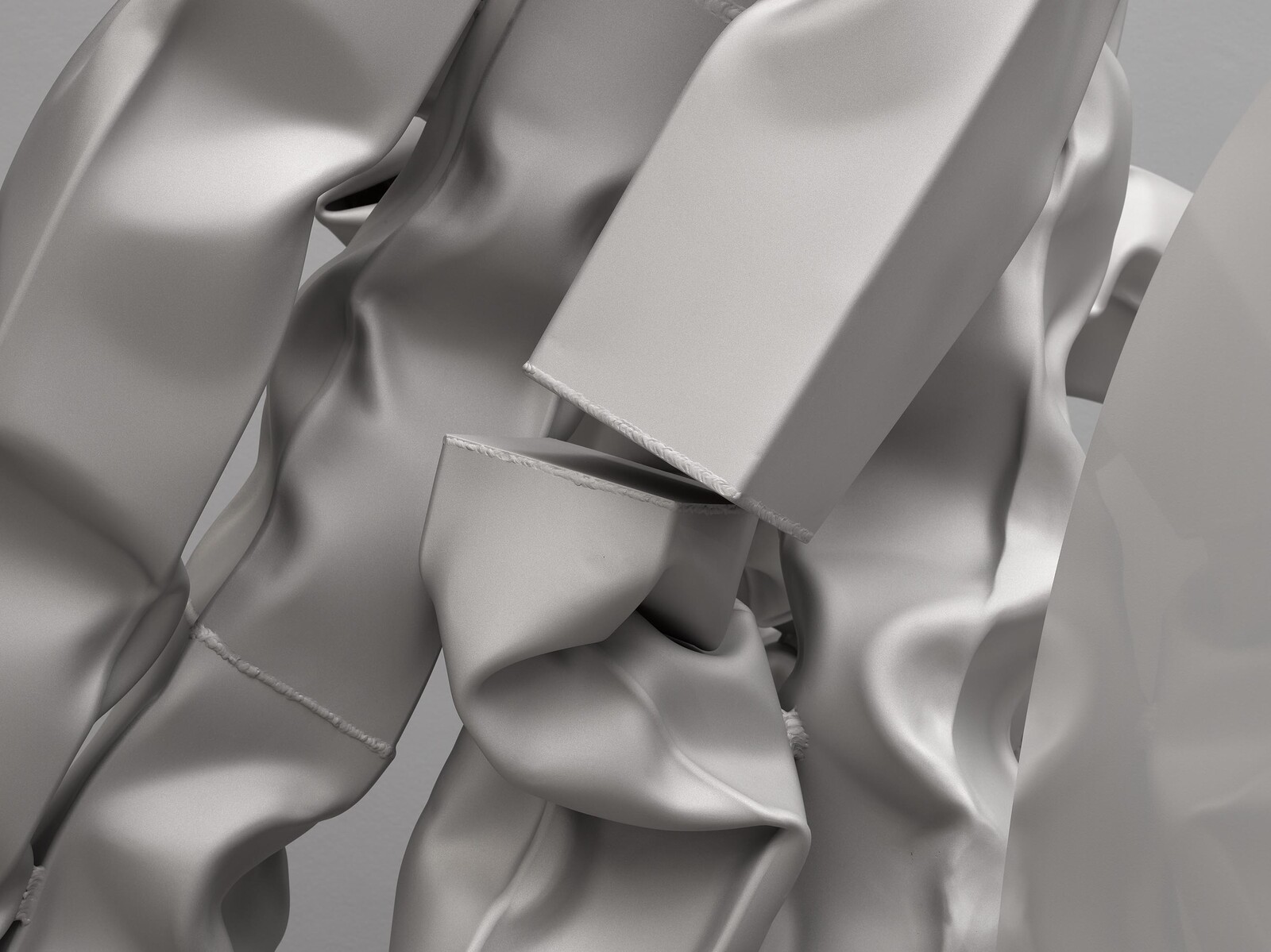

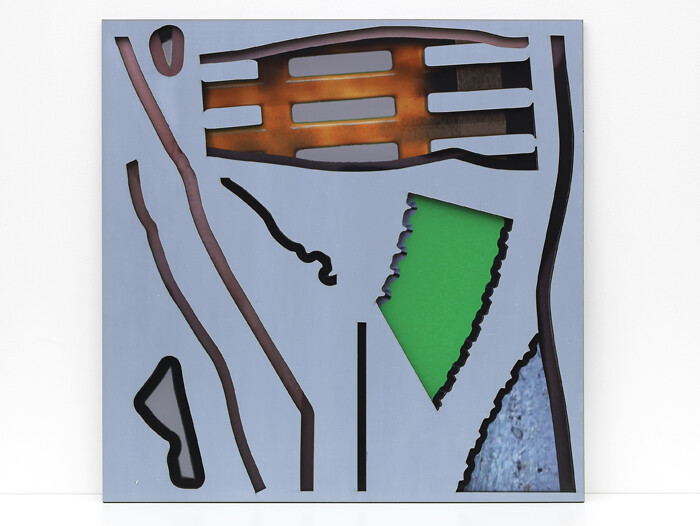

Saskia Noor van Imhoff’s “Mineral Lick”

Tom Jeffreys

In 2021, Saskia Noor van Imhoff purchased a dairy farm amid the polder landscapes of Friesland in the Netherlands. The farm had been active for some four hundred years, but derelict for the past fifteen. van Imhoff approaches the site as a research project, entitled Rest, with the implication that the land, exhausted after centuries of extractive management, now finally has the chance to recover. With the land recuperating, the artist set to work: reactivating the farm not only as a site of agricultural production (prioritizing a certain conception of environmental responsibility over a profit motive) but also as a place for workshops, symposia, and other interdisciplinary activity. Meanwhile, van Imhoff has also reoriented her practice in response to the land, its historic uses and possible futures.

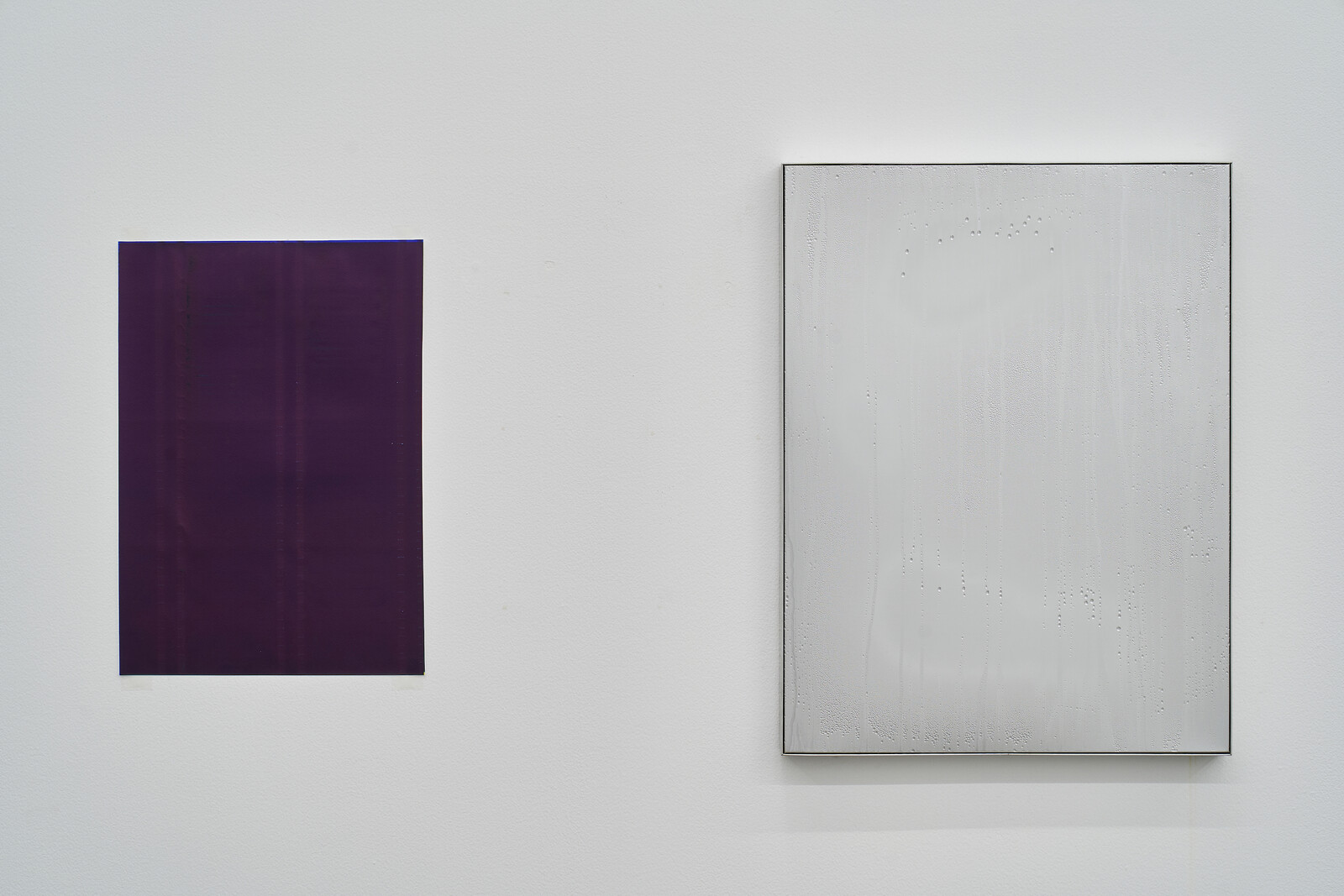

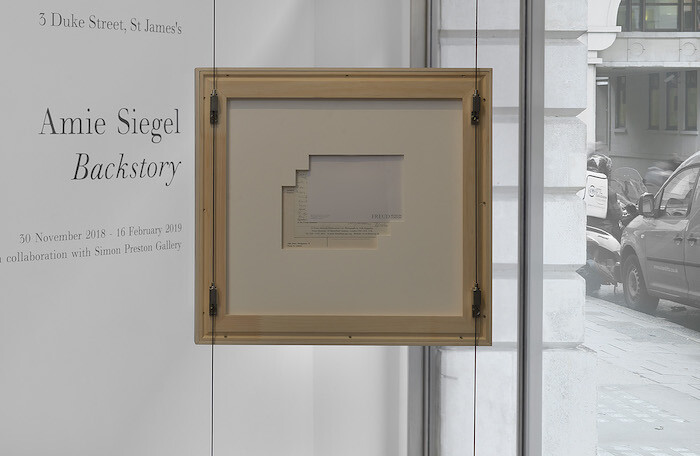

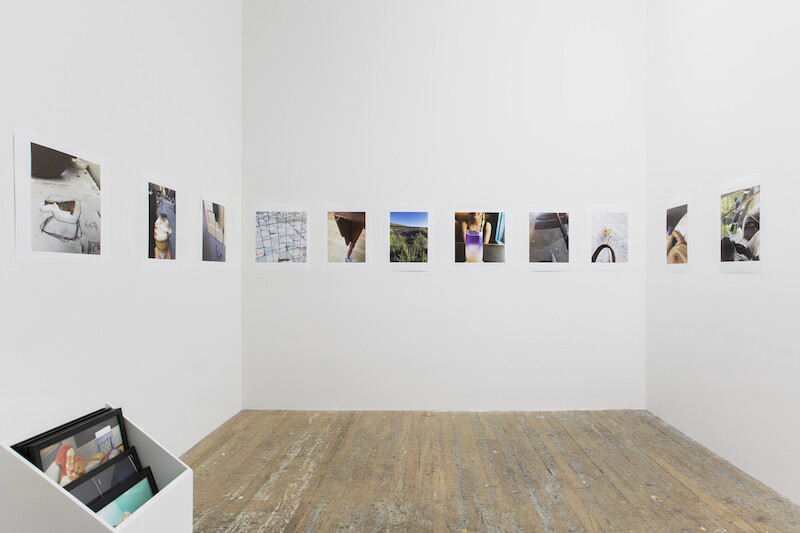

“Mineral Lick” is the first UK solo show for van Imhoff, whose previous work has focused on hierarchies of value within collecting institutions such as museums and archives. Here, she foregrounds unexpected material combinations underpinned by a fascination with grafting, hybridity, and the recontextualizing of materials. GRIMM’s street-level windows have been washed with white shading paint and the interior glows with pink-red light—both echoes of the forced growing conditions of commercial greenhouse production. …

March 16, 2024 – Review

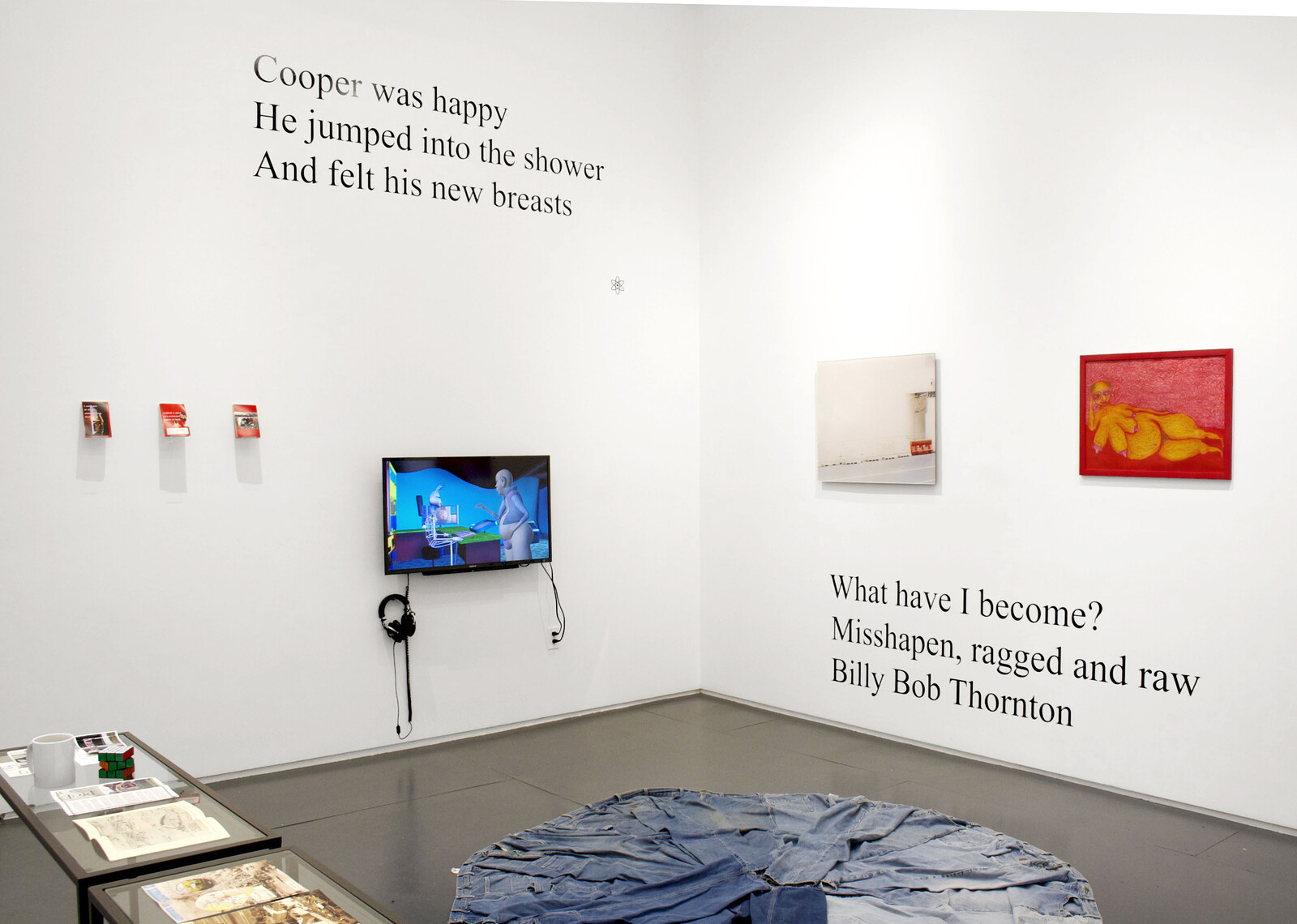

“El fin de lo maravilloso. Cyberpop en México”

Gaby Cepeda

In her curatorial text for this group exhibition of Mexican artists mostly born in the nineties, Karol Woller Reyes defines a “generational imagination.” It belongs to artists who have “naturally incorporated some creative strategies” such as digital montage and circuit bending into the production of paintings and sculptures that also abound with references to pop-cultural figures from Pokémon to Pepe the Frog. The implication is that the art of today is shaped by the technologies and media environment of its makers’ adolescence. Shared access to cable TV and computers during childhood does not, however, a generation make.

One of the narrow aisles that encircles the warehouse-like main gallery at Museo El Chopo housed the first, smaller part of “El Fin de lo Maravilloso.” Tucked to the side of the glass-walled gift shop were pieces by YOPE Projects collective crowded into a scaffold structure resembling an open-air market; a very early José Eduardo Barajas painting of cloudy emoji-like figures (Cirrus, Socrates, particle, decimal, hurricane, dolphin, tulip, Monica, 2018) in a freestanding wooden frame; and ¿Estamos, Kimosabe? (2020) a much-exhibited soft sculpture of a Mexican Bugs Bunny by Paloma Contreras Lomas—which judging by the dirt on its paws, has seen better days. …

March 15, 2024 – Review

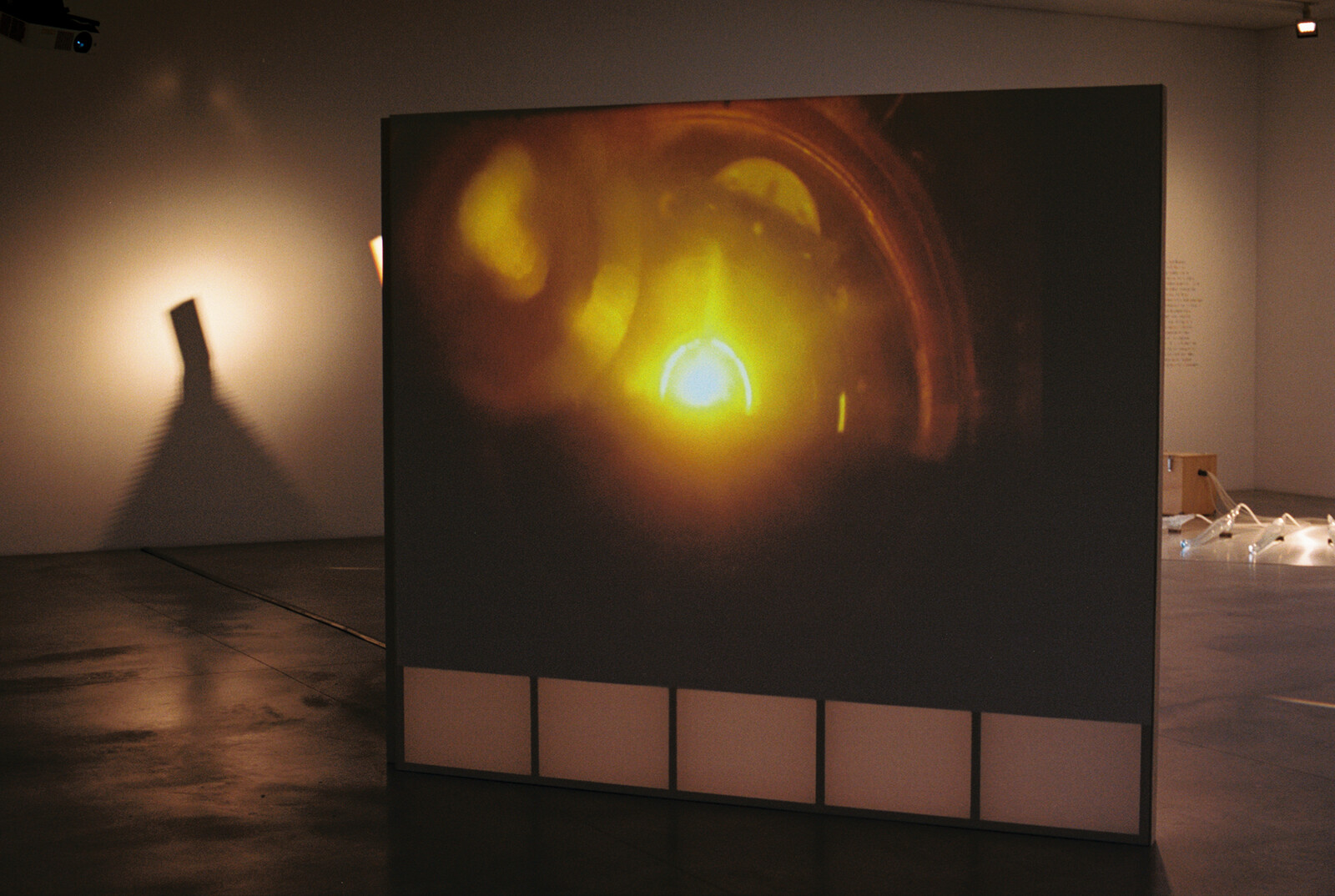

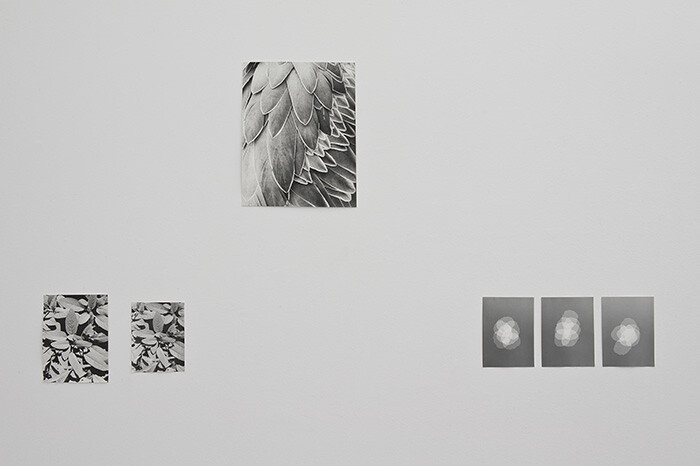

Mary Helena Clark’s “Conveyor”

Chris Murtha

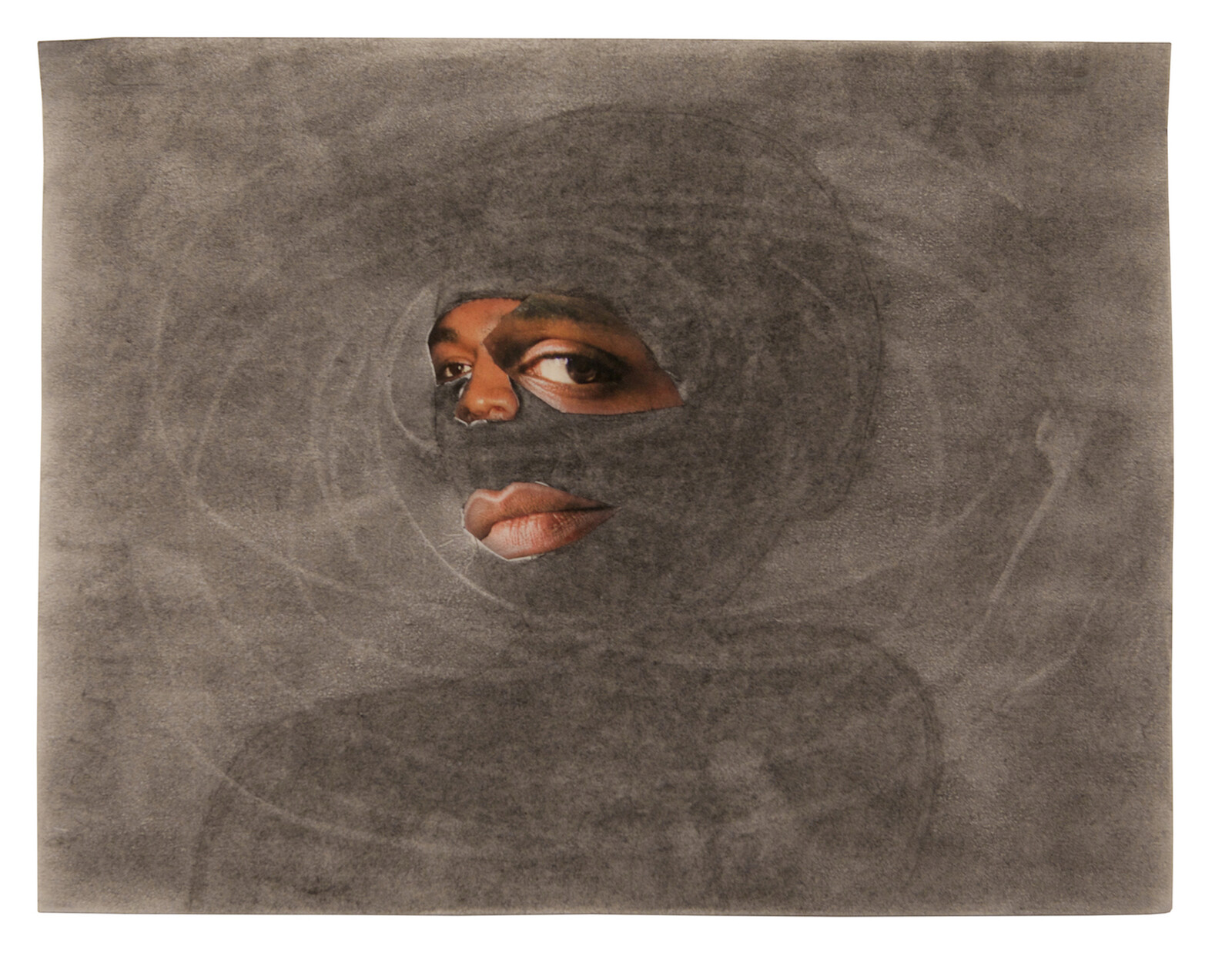

There’s a card trick midway through Mary Helena Clark’s Neighboring Animals (all works 2024 unless otherwise stated), a two-channel video projected into a darkened corner. While an elderly orangutan watches from the other side of his enclosure’s window, two human hands press a single playing card against the thick safety glass. Holding a stick in one hand, the ape nimbly picks up the card, now (miraculously!) on his side of the barrier. After giving it a sniff and twirling it around in his hands, he places it back on the glass, tapping it a few times with his makeshift wand—perhaps his attempt to send it back through the seemingly porous window. Clark edited this video—a zoo’s promotional clip gone viral—to preserve some mystery on behalf of the orangutan, cutting the ending so that the card, instead of falling to the ground, remains affixed to the glass.

A collage of sampled footage, still pictures, medical scans, and her own camerawork, Neighboring Animals scrutinizes the thresholds between inside and outside, human and beast. The left channel consists solely of yellow subtitles with no corresponding voice, a pastiche of quotations on the topic of disgust. Alongside illustrations of chained and leashed animals from …

March 13, 2024 – Review

Esther Mahlangu’s “Then I Knew I Was Good at Painting”

Ben Eastham

This retrospective of the Ndebele painter and unofficial artist laureate of post-Apartheid South Africa presents two origin stories. The first, from which its title derives, tells of how Esther Mahlangu first identified as an artist when, having been reprimanded for daubing the walls of her family home as a child, she persevered until she was good enough to be permitted by her mother to paint its façade. The second, taking place several decades later, arrived when a group of European researchers came to her village to seek out the woman responsible for decorating the house in their photograph. “We want you,” they said, “to come to Paris.”

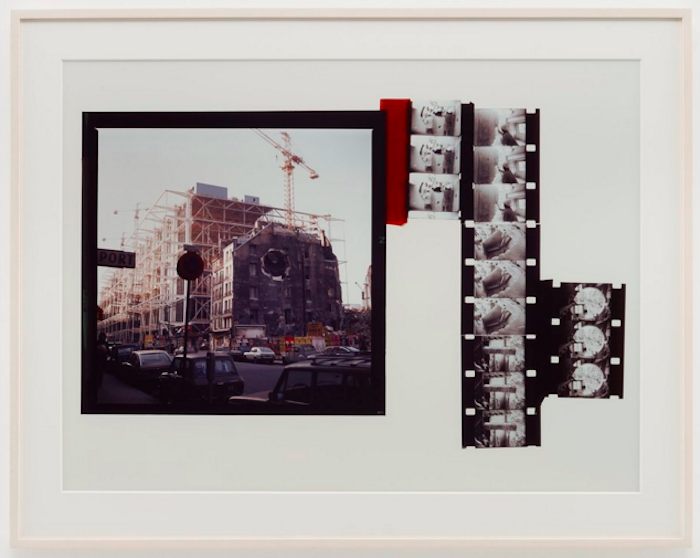

The invitation was to participate in the 1989 exhibition “Magiciens de la Terre” at the Centre Pompidou, a show that continues to cast a long shadow over attempts to decenter or decolonize the representation in western institutions of global visual culture. Mahlangu contributed a reproduction of her own painted Ndebele house (reproduced in miniature in this exhibition), setting in train a career so prolific that her vivid polychromatic designs now serve as visual shorthand for Nelson Mandela’s vision of South Africa as a comparably vibrant and harmonious “rainbow nation.” These instantly recognizable patterns—since …

March 12, 2024 – Review

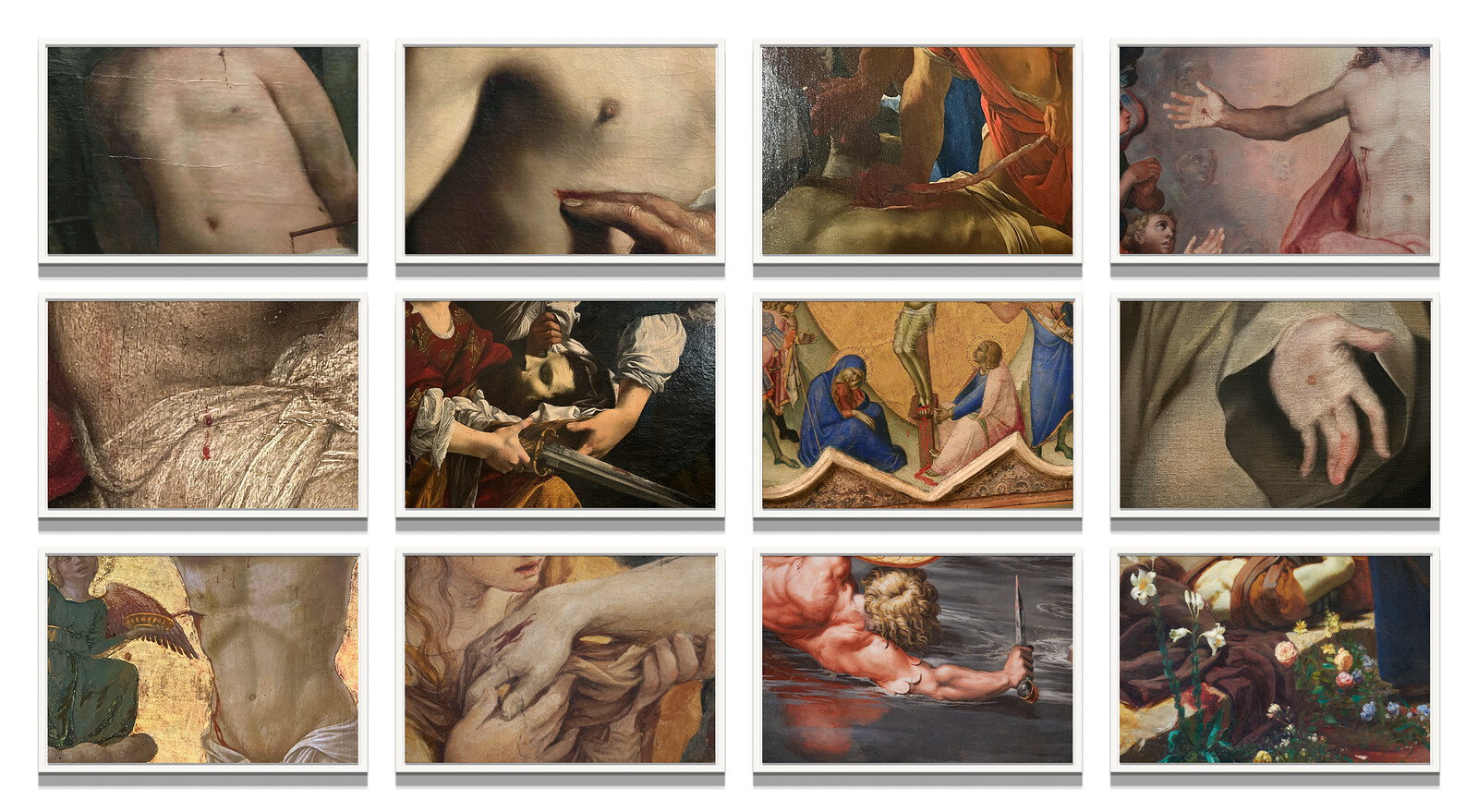

Catherine Opie’s “Walls, Windows, and Blood”

Sylvie Fortin

They say ghosts, vampires, and the soulless cast no shadows. Shot in a Vatican City emptied of visitors during the pandemic summer of 2021, Catherine Opie’s new photographs provocatively reshuffle different threads of her longstanding inquiries—the spectrum from transparency to opacity; communal spaces; the body as/and architecture; queerness and institutions. With its succinct, descriptive enumeration, the exhibition’s trinitarian title “Walls, Windows, and Blood” implies unsettling visual conversations to which she gives form with a selection of images from three new series (all works 2023), clustered in grids, lined up along walls, and proceeding in colonnades.

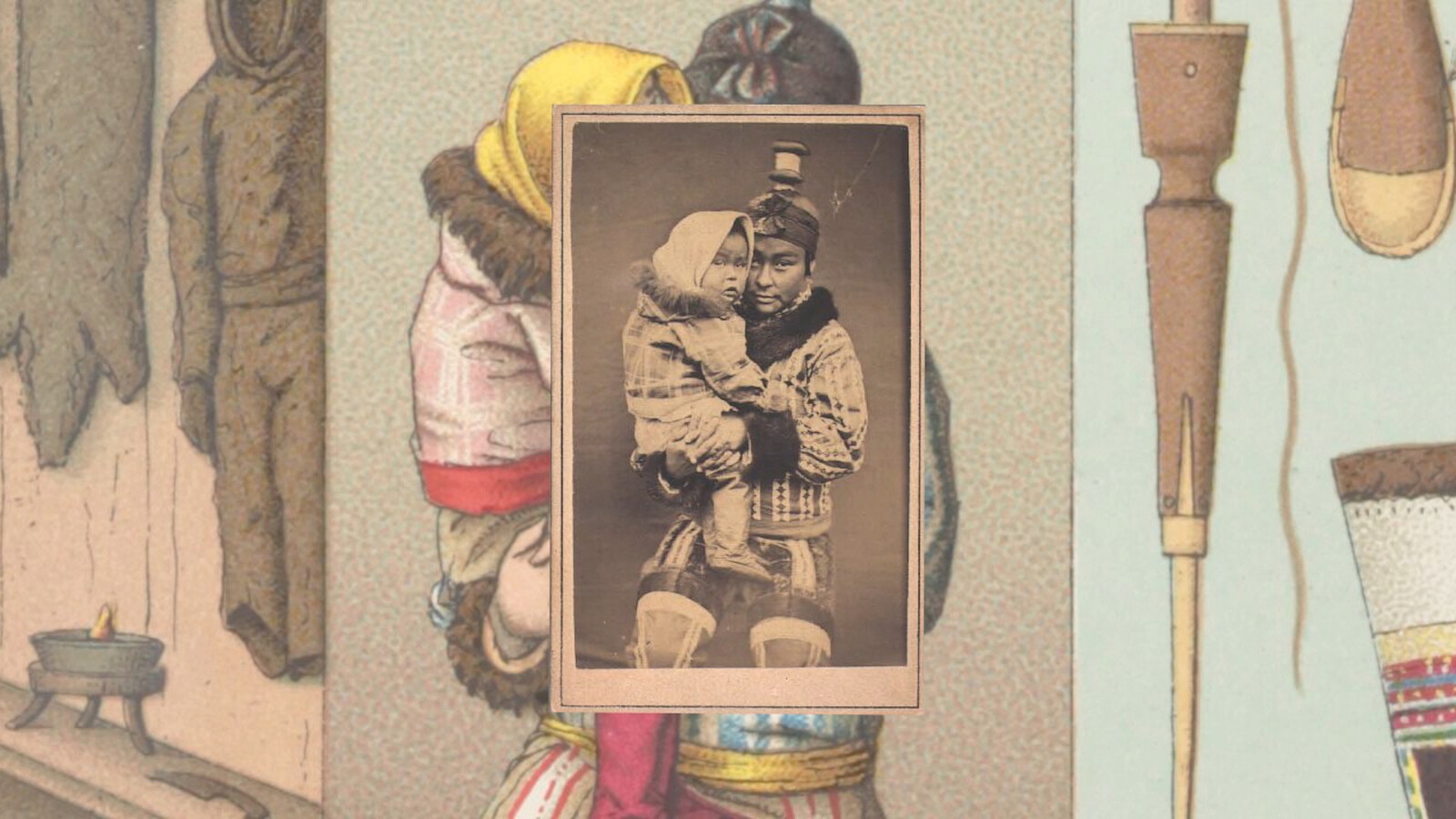

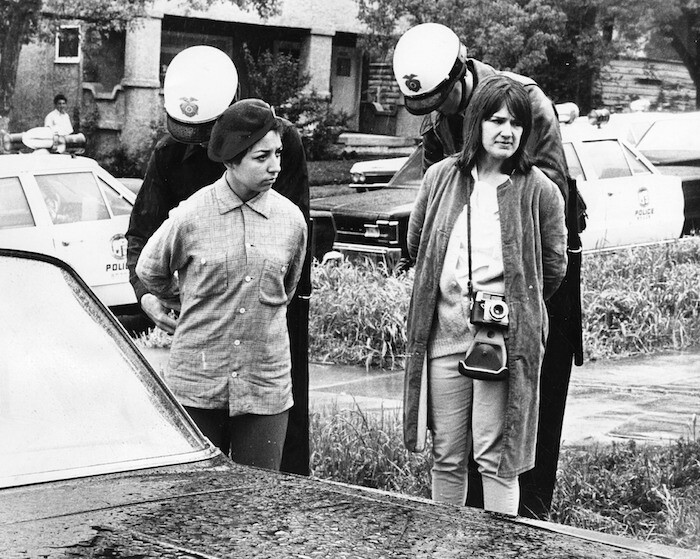

No Apology (June 5, 2021), a large photograph of Pope Francis delivering a speech from a top-floor window of his residence overlooking St. Peter’s Square, greets visitors. A lone white man dwarfed by statuary and muffled by the resounding whiteness of the colonnaded plaza, he floats above a blood-red banner bearing his coat of arms. In his short allocution, uttered in the wake of the traumatic discovery of unmarked graves at the former Church-run Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, the pontiff acknowledged (apologies would have to wait) the Catholic Church’s complicity in both the colonial dispossession of Canada’s Aboriginal communities and the accompanying systematic …

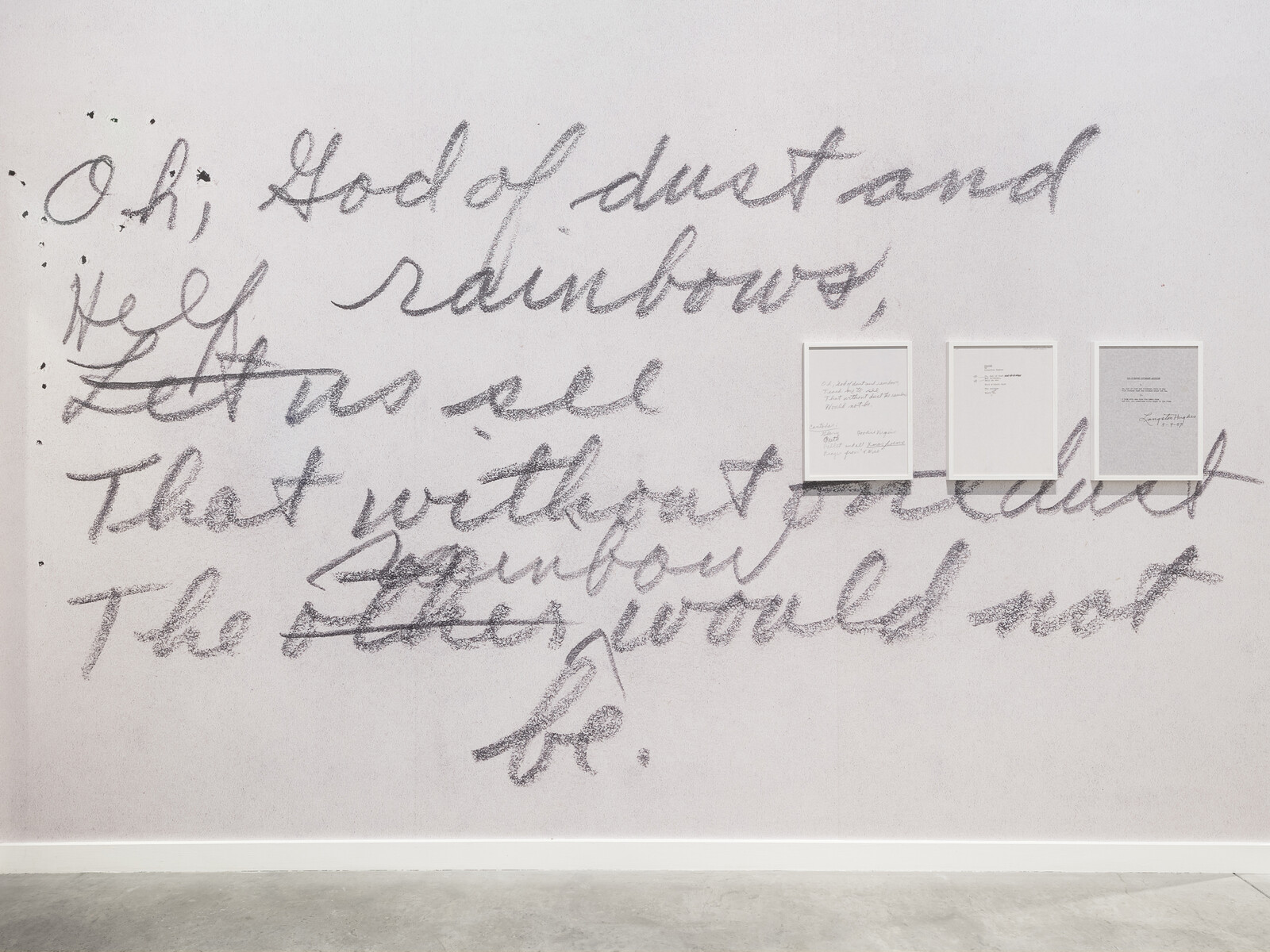

March 8, 2024 – Review

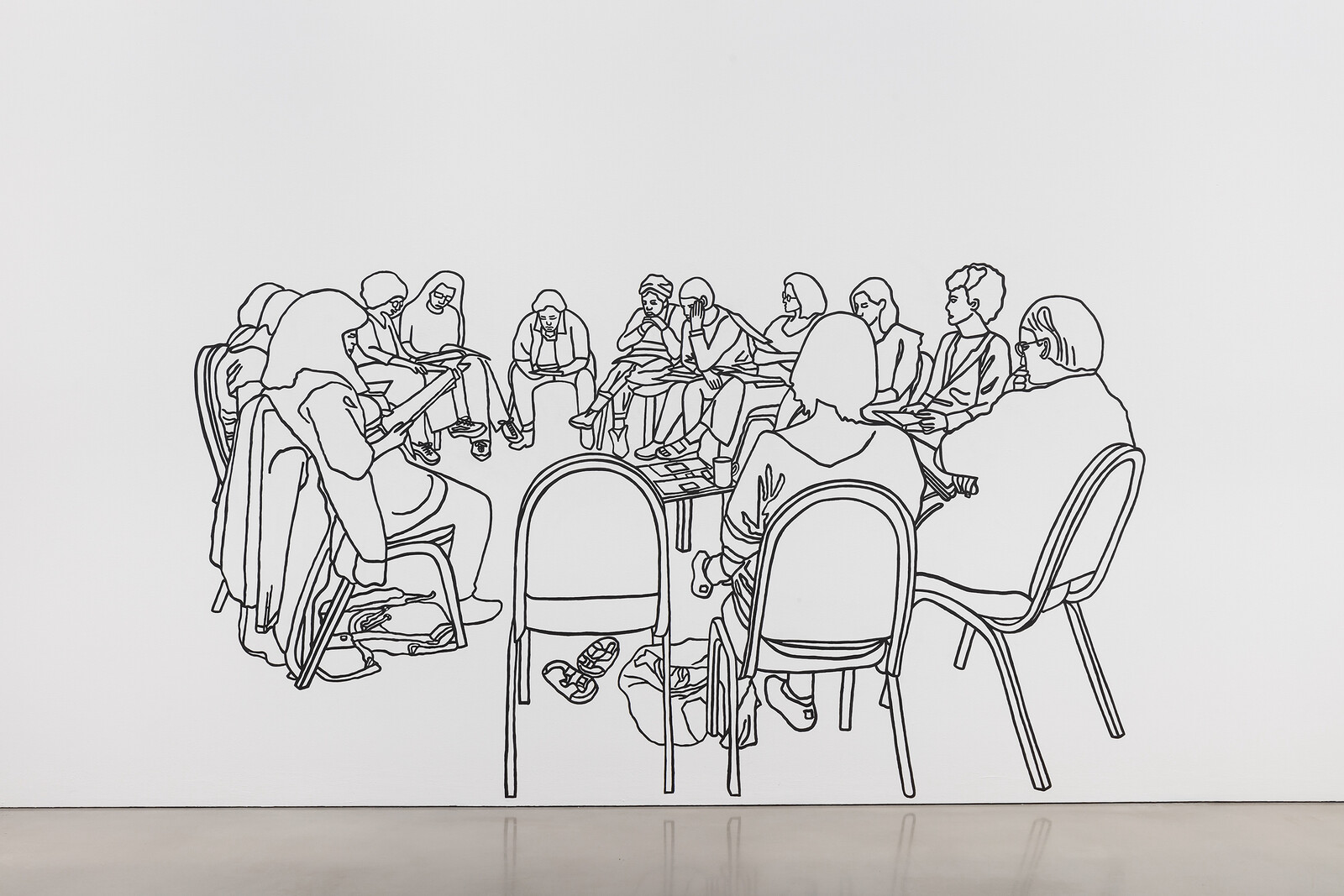

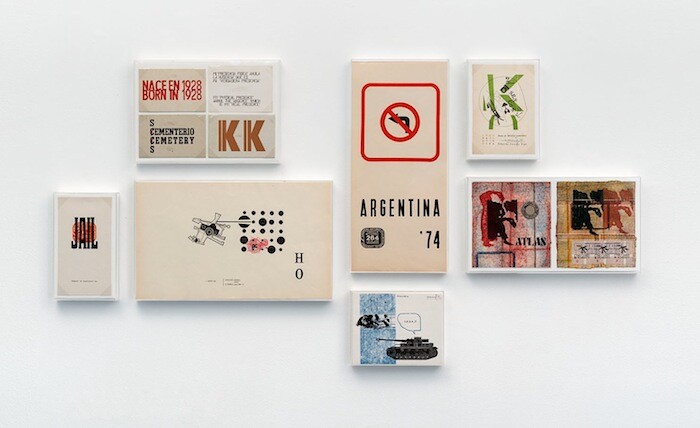

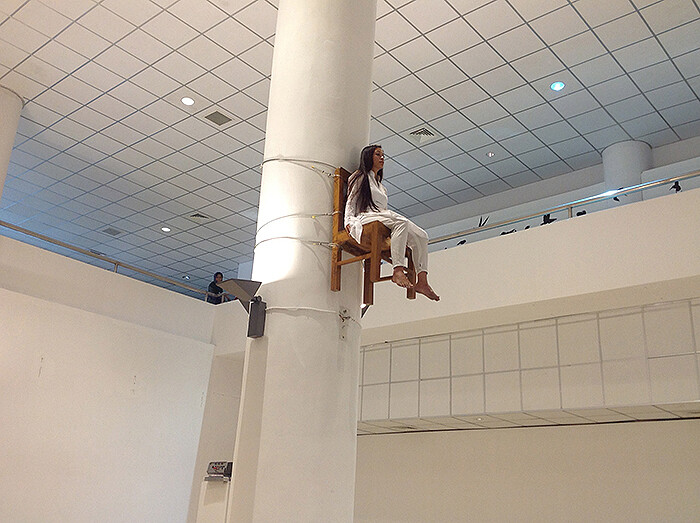

Amalia Pica’s “Aula Expandida”

Noah Simblist

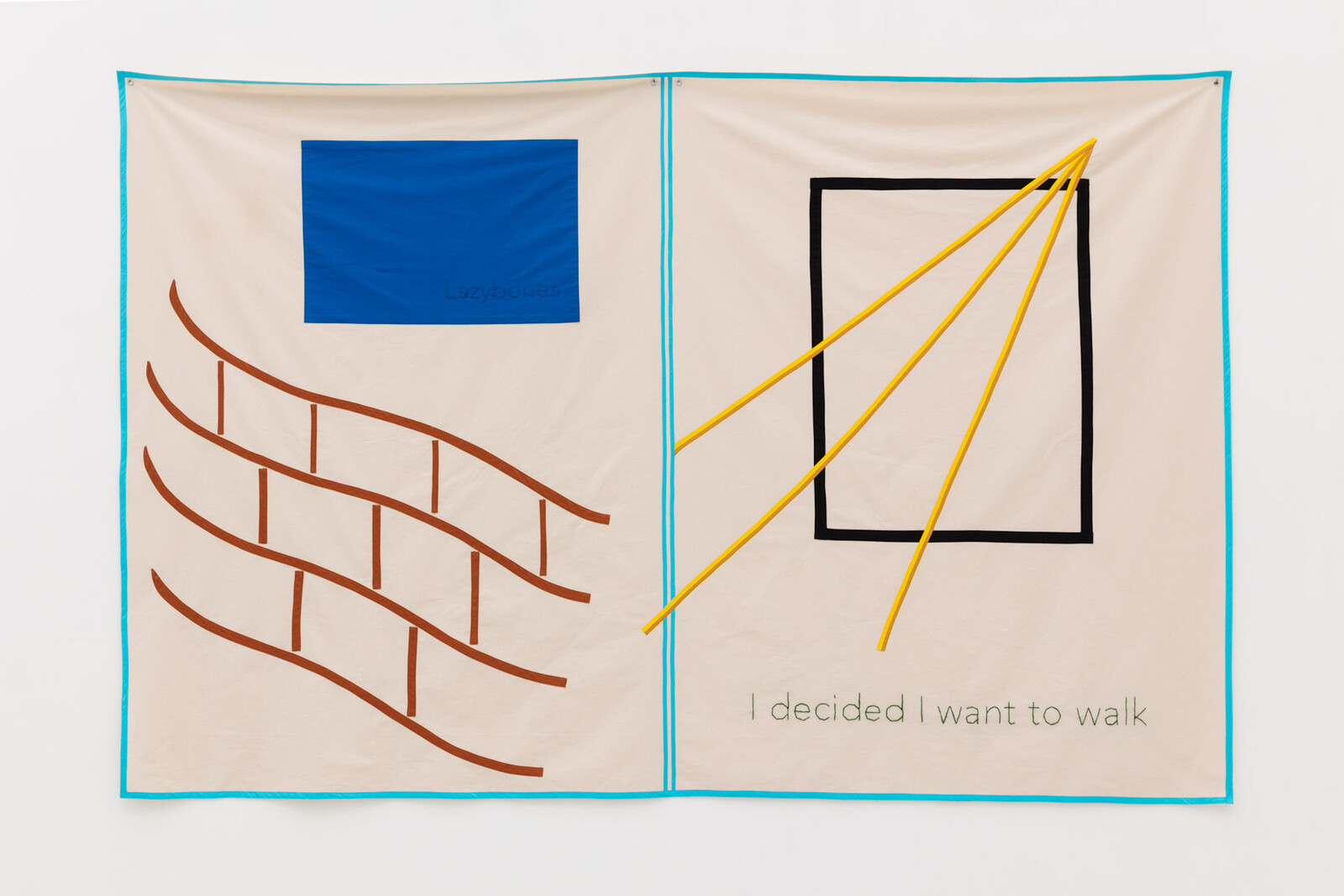

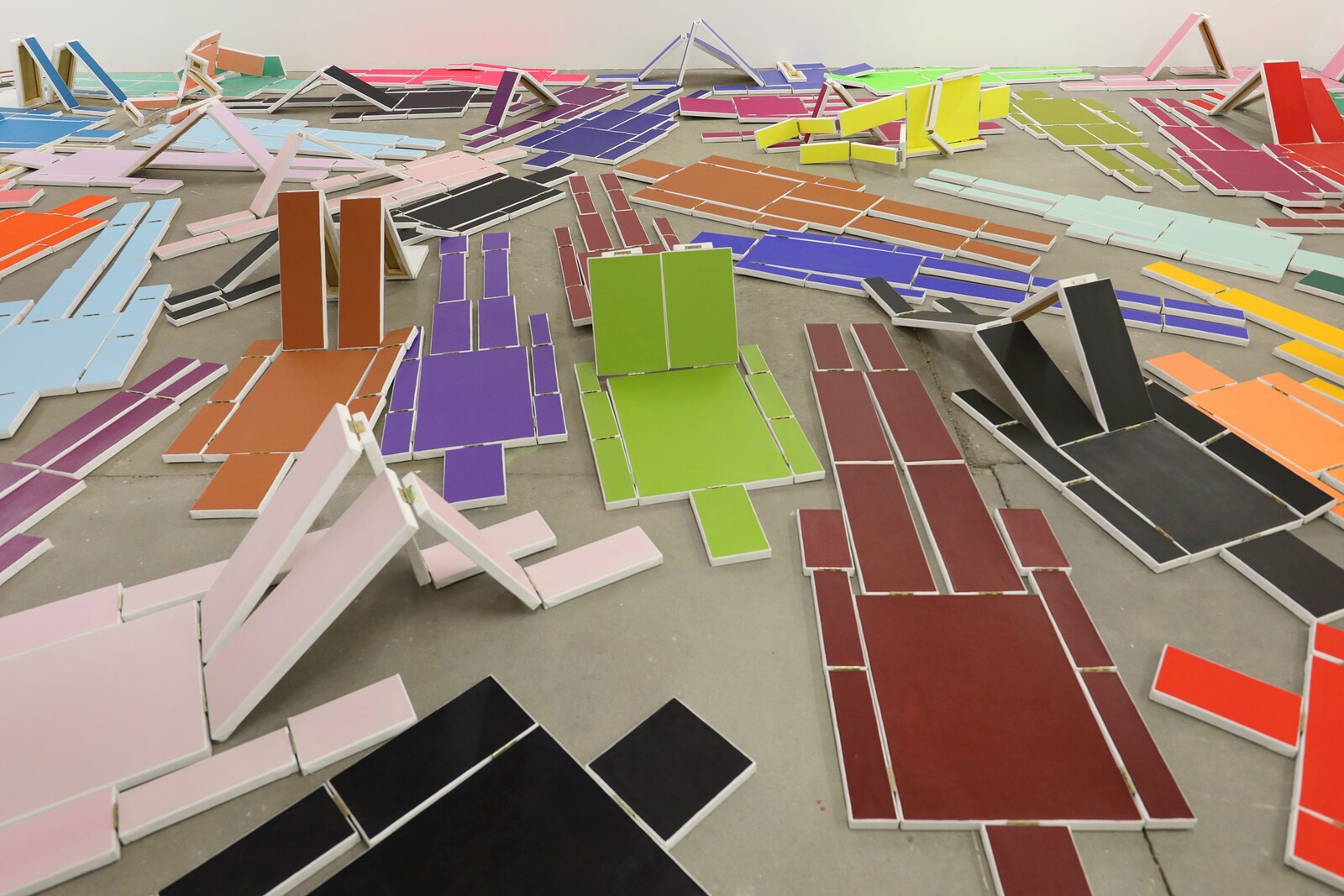

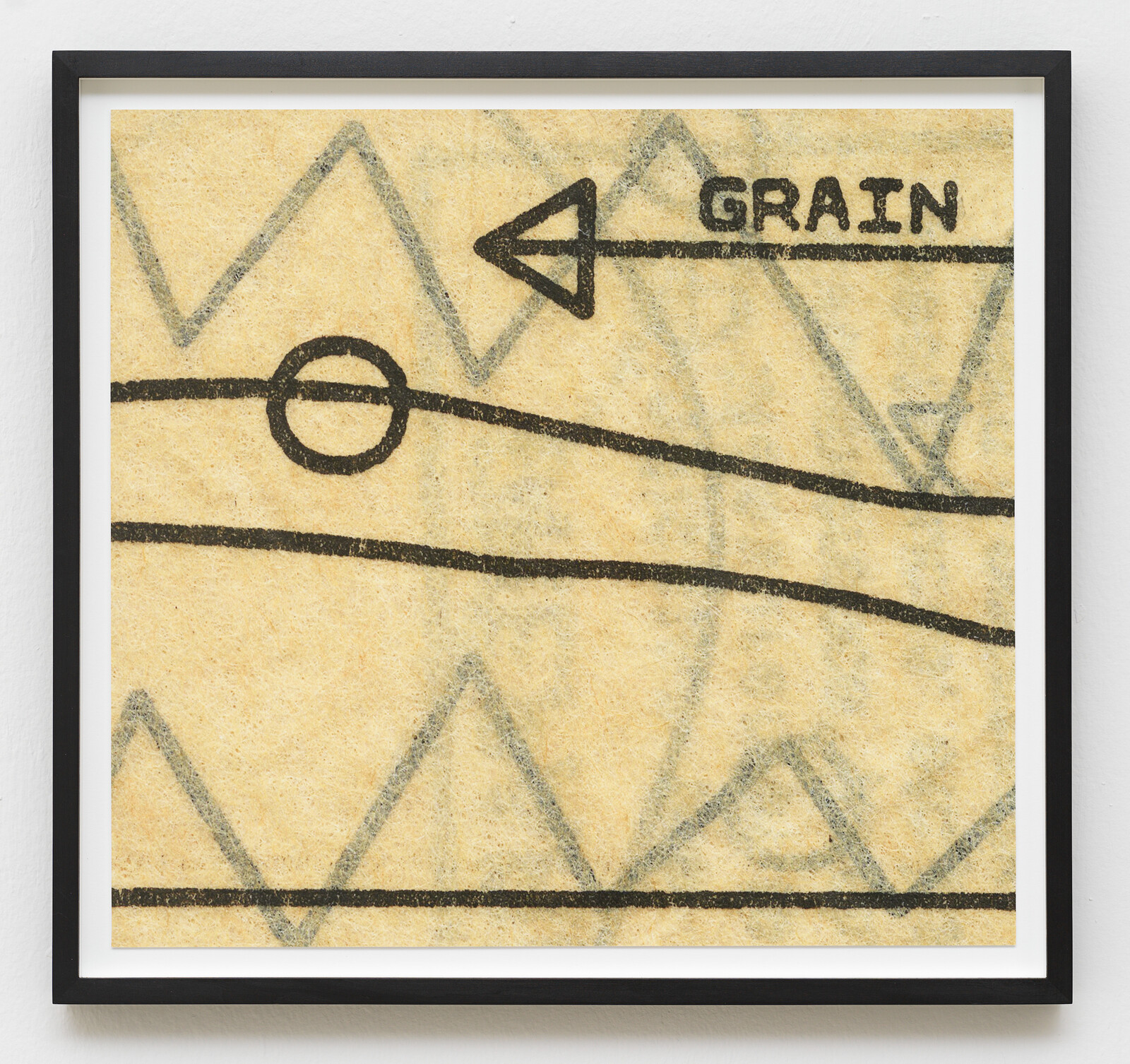

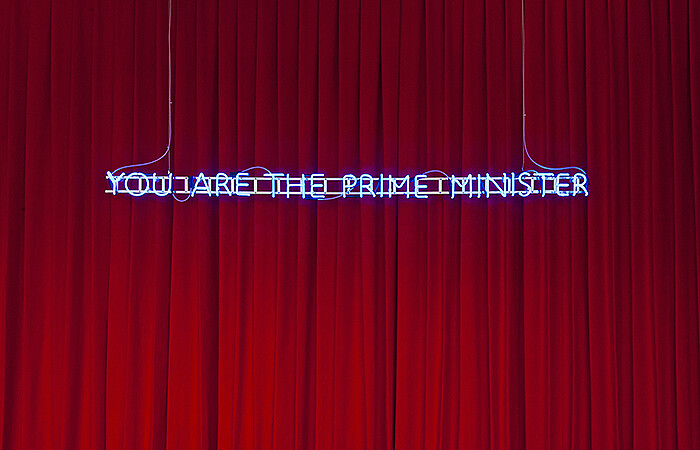

How might our understanding of education better incorporate communication, participation, and play? And what would be the consequences of that expanded approach? Such questions have been at the center of Amalia Pica’s work for many years, drawing partially on her early experience as a primary school teacher. Her first solo exhibition in New York attends to the manifold aspects of learning across a group of collages, sculptures, and video works organized around a new interactive installation.

Two understated large-scale graphite and watercolor drawings, School sheets in adjusted scale (or an exercise in how to go back to all the things I hadn’t thought of yet) #1 and #2 (both 2011), are based on notebook paper with “Rivadavia” printed in an elegant cursive in the margin. This references Bernardino Rivadavia, the first president of the London-based artist’s birth country of Argentina, using a font based on his signature. The stamping of state power into the very books in which young people learn how to write signals the reproduction of the ideological subject through a form of repeated inscription. This has chilling implications in the context of the military dictatorship (1976–83) into which Pica was born.

Her 2008 video On Education depicts …

March 7, 2024 – Review

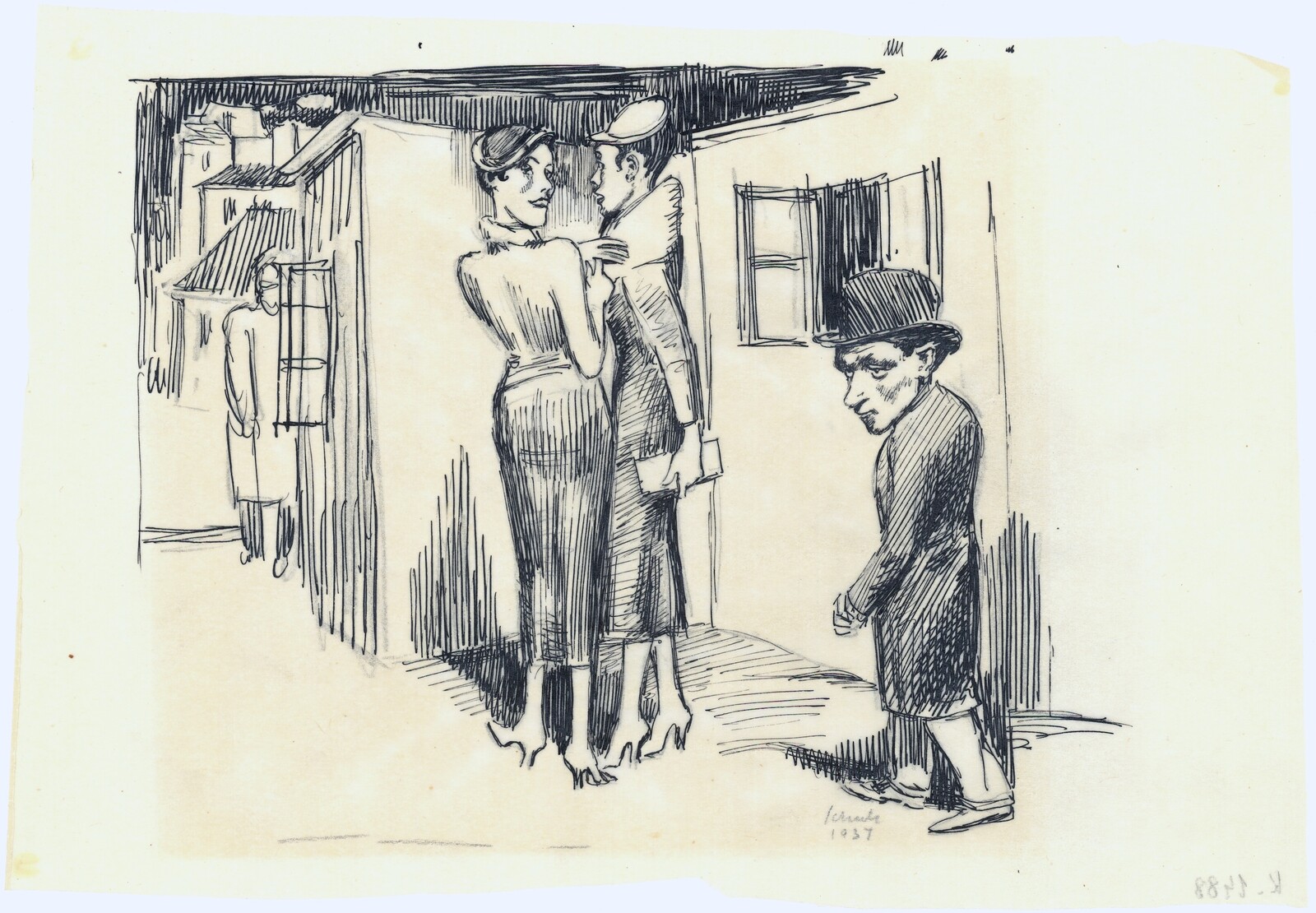

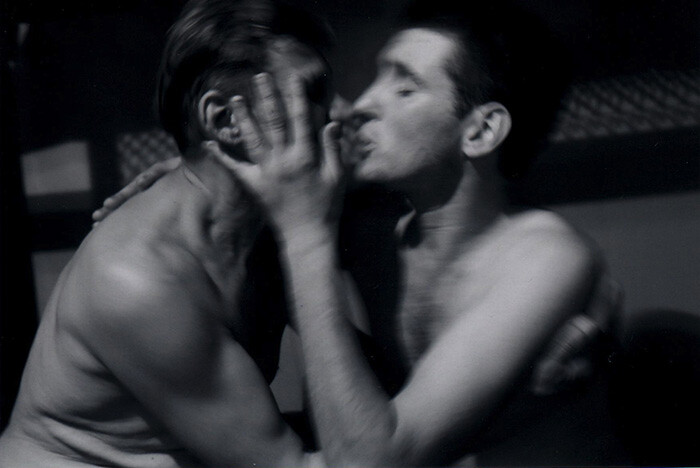

“Fokus: Hamed Abdalla”

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

The Egyptian artist Hamed Abdalla painted mothers and farmers and letters and landscapes but the subjects he returned to most often, in each of the many disparate phases of his career, were lovers. This jewel box-sized exhibition devoted to Abdalla’s work, organized by Morad Montazami and Madeleine de Colnet of the Paris-based publishing and curatorial project Zamân, features six of his amorous pairings. The earliest lovers in the show are Les Amants de Shemm Ennessim [The Lovers of Shemm Ennessim], from 1953, a sweet gouache on silk paper showing a couple in traditional dress, facing each other demurely in profile but slyly extending their arms to embrace. The figures appear stylized and flattened, and clearly, Abdalla was inspired by a celebrated genre of hand-painting on glass depicting Antar and Abla. Those two are the hero and heroine of pre-Islamic poetry (composed by Antar himself, full name Antarah Ibn Shaddad) relating the episodic adventures of a black warrior poet who was born a slave but became a knight and the smart, beautiful woman who defied her family to be with him.

The last of Abdalla’s lovers, in a show conceived as part of a series and wedged into the museum’s permanent …

February 29, 2024 – Review

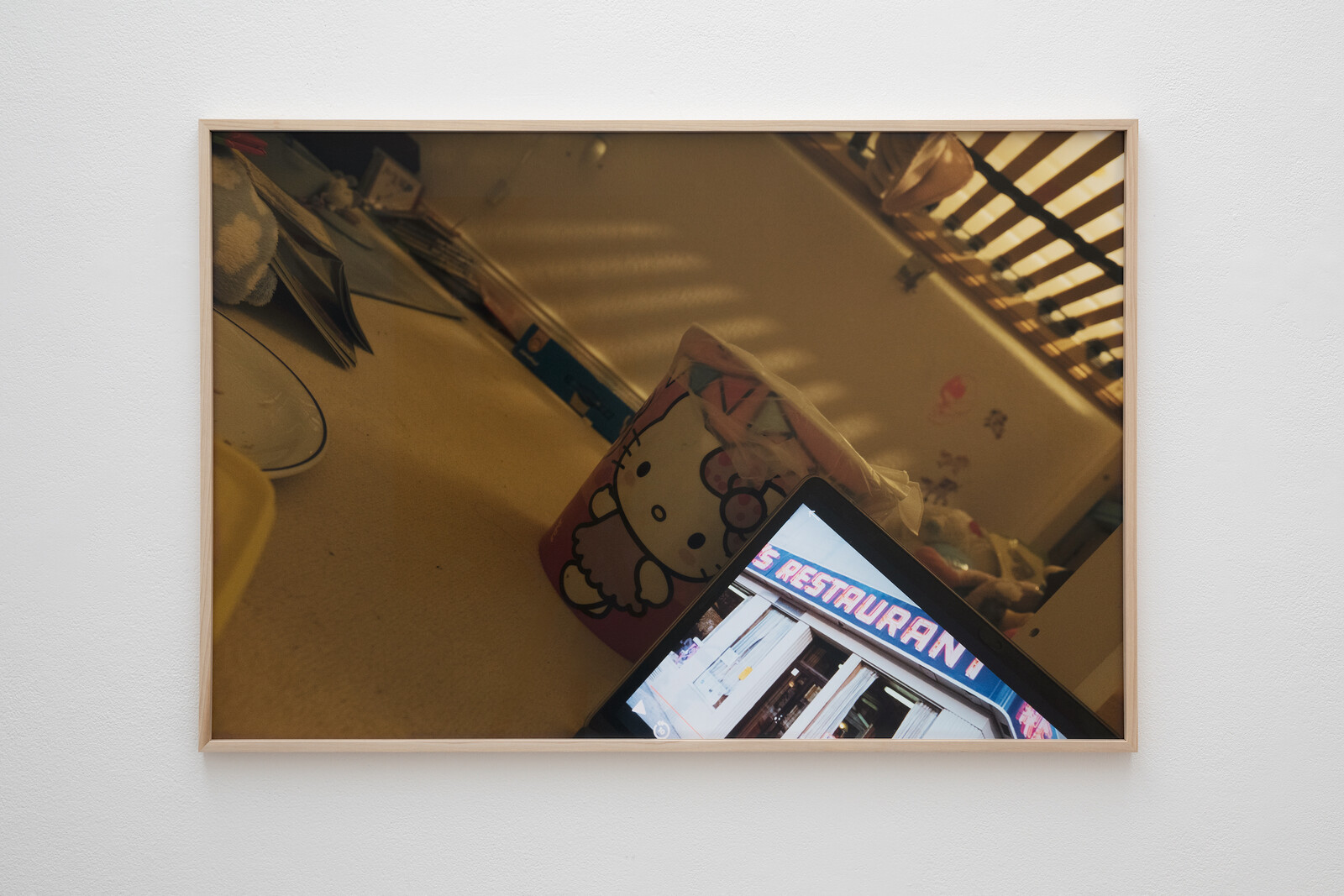

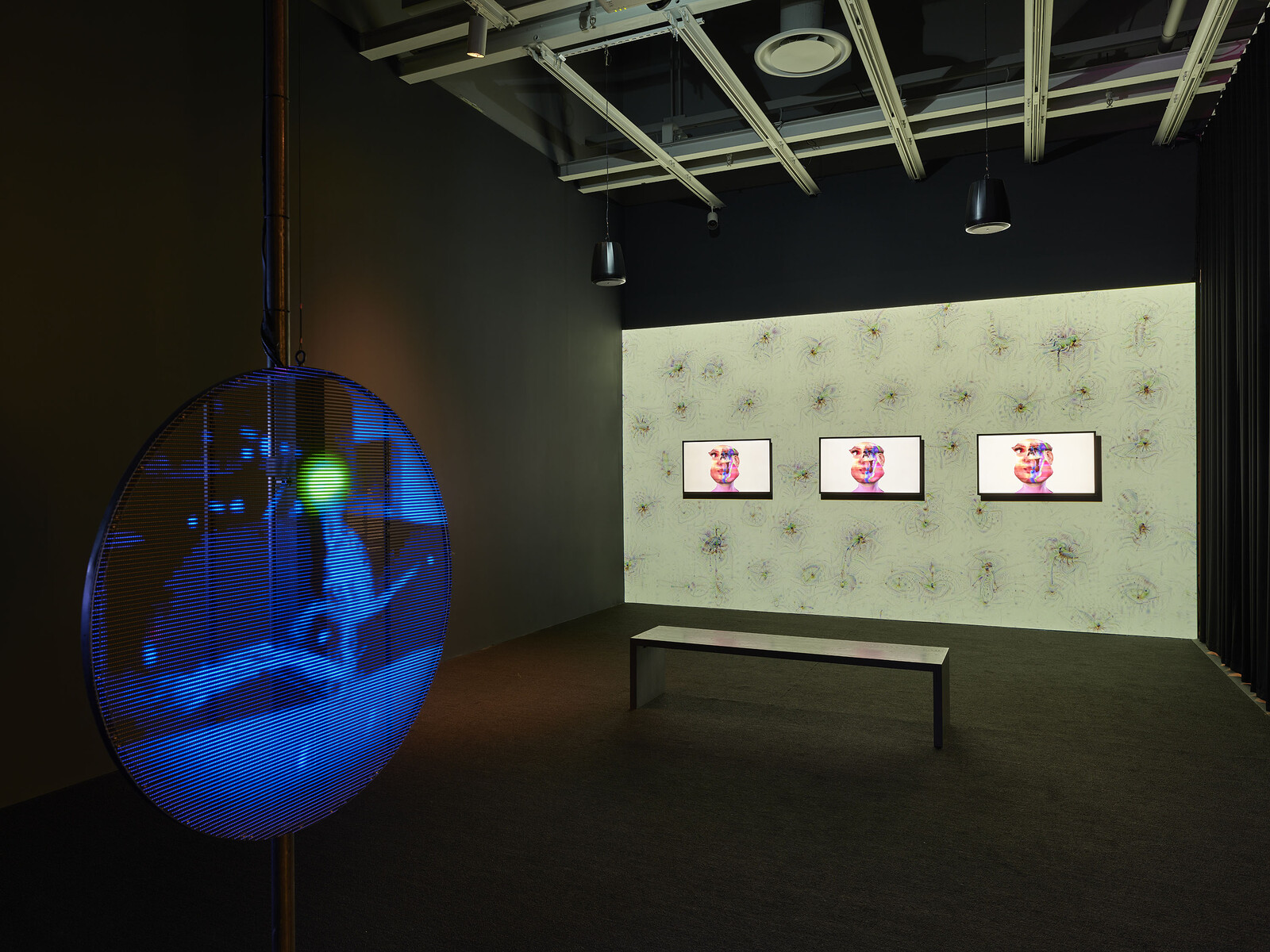

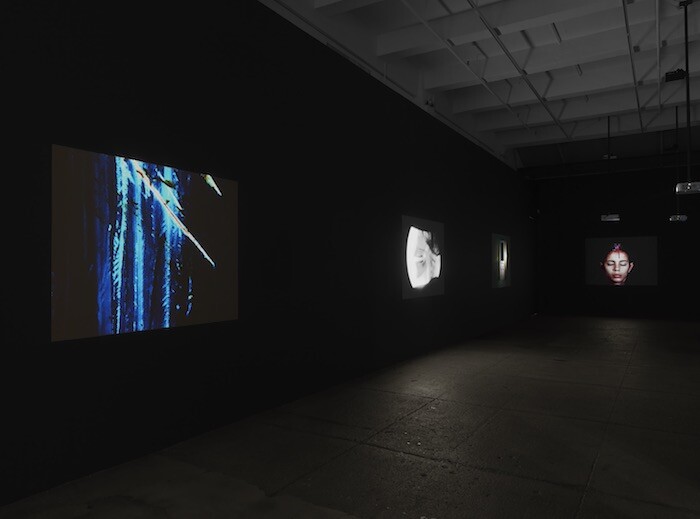

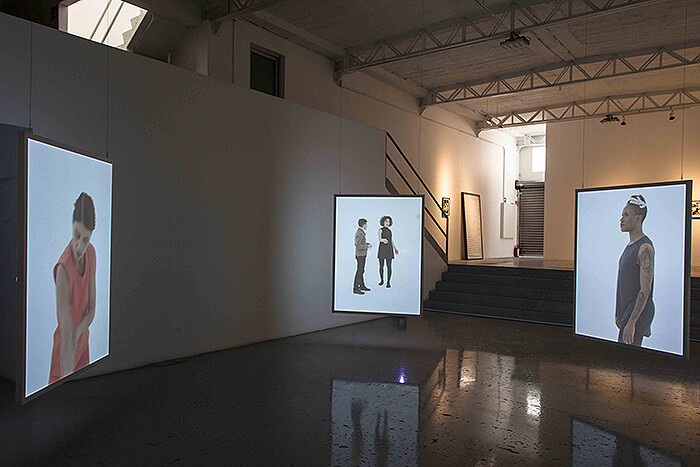

“Another Beautiful Country: Moving Images by Chinese American Artists”

Vanessa Holyoak

The Chinese term gūanxi describes a web of relations between friends, family, lovers, co-workers, even corrupt politicians. It evokes a sense of community and belonging that can prove elusive for the diverse group of people commonly referred to as “Chinese American.” A moniker that points to allegiances, however fraught, to the two countries it references, “Chinese American” is a one-size-fits-all label that attempts to forge a singular identity out of a heterogeneous array of diasporic experiences shaped by displacement, immigration, and cross-cultural translation.

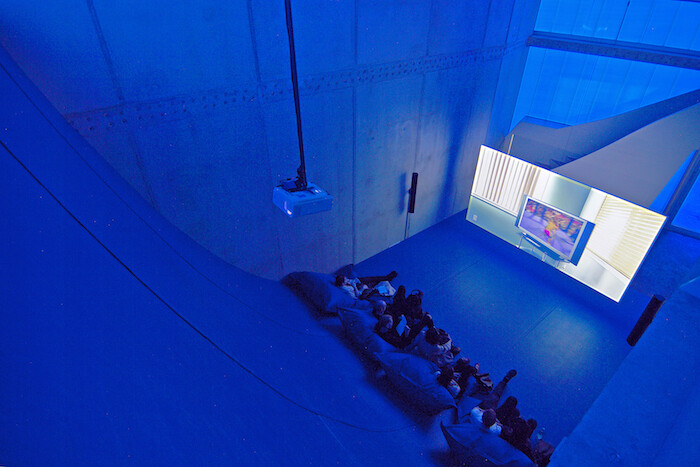

Curated by Dr. Jenny Lin, “Another Beautiful Country: Moving Images by Chinese American Artists” hinges on another transcultural exchange. Drawing connections between gūanxi and French-Martinican philosopher of opacity Édouard Glissant’s notion of a “poetics of relation,” the exhibition posits relationality over identity as an alternate cornerstone of contemporary Chinese Americanness. Referenced in an introductory essay in the exhibition catalogue written by Dr. Lin, Glissant’s emphasis on diasporic relation is espoused throughout the show—which includes areas for repose and relation amongst exhibition-goers—and enacted through real and speculative social encounters between family, friends, and strangers staged within the works themselves. Drawing its title from the Chinese word for America, 美國/měiguó, which translates literally to “beautiful country,” along with the …

February 28, 2024 – Review

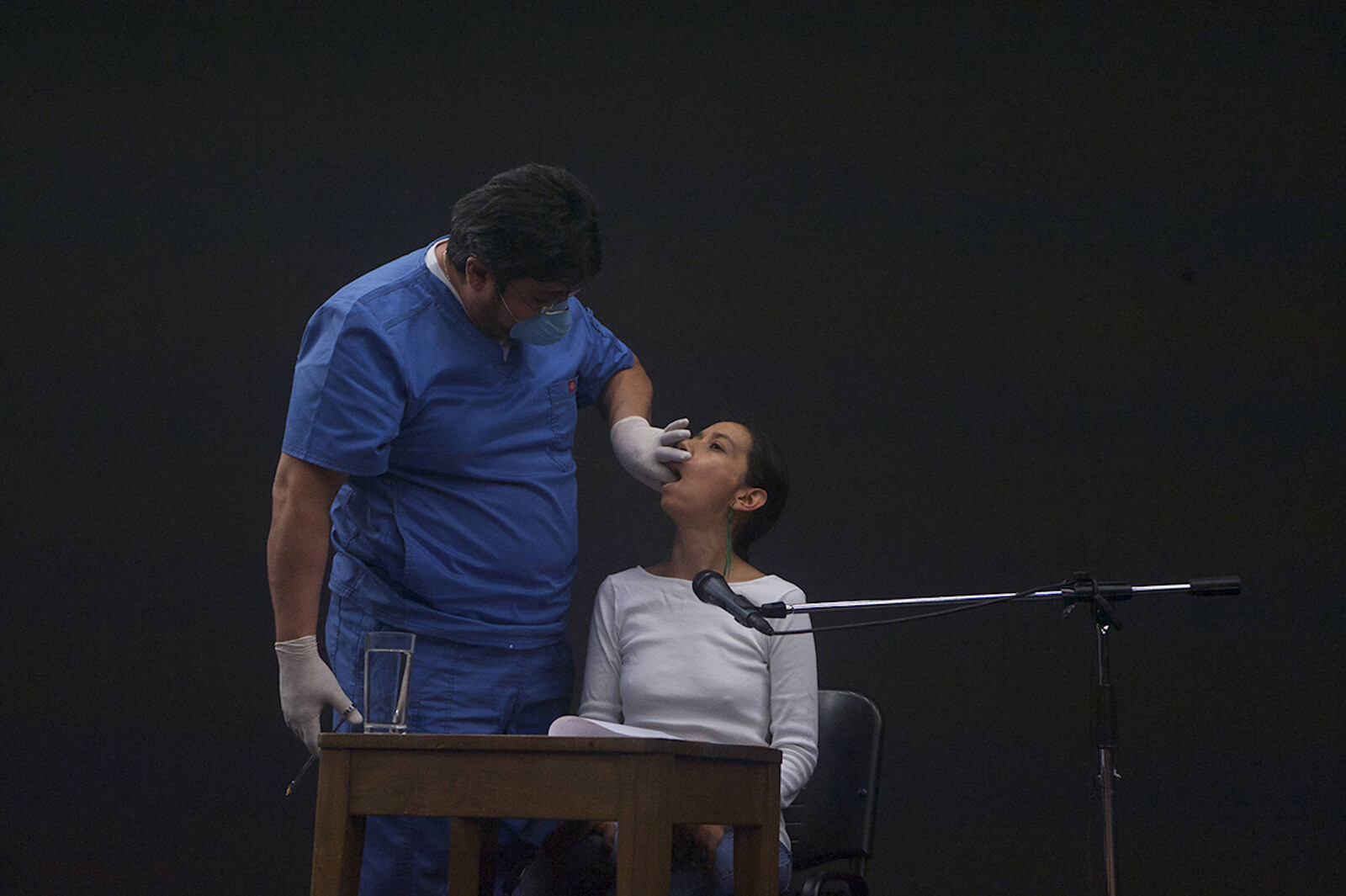

Tania Bruguera’s “Where Your Ideas Become Civic Actions (100 Hours Reading The Origins of Totalitarianism)”

Eugene Yiu Nam Cheung

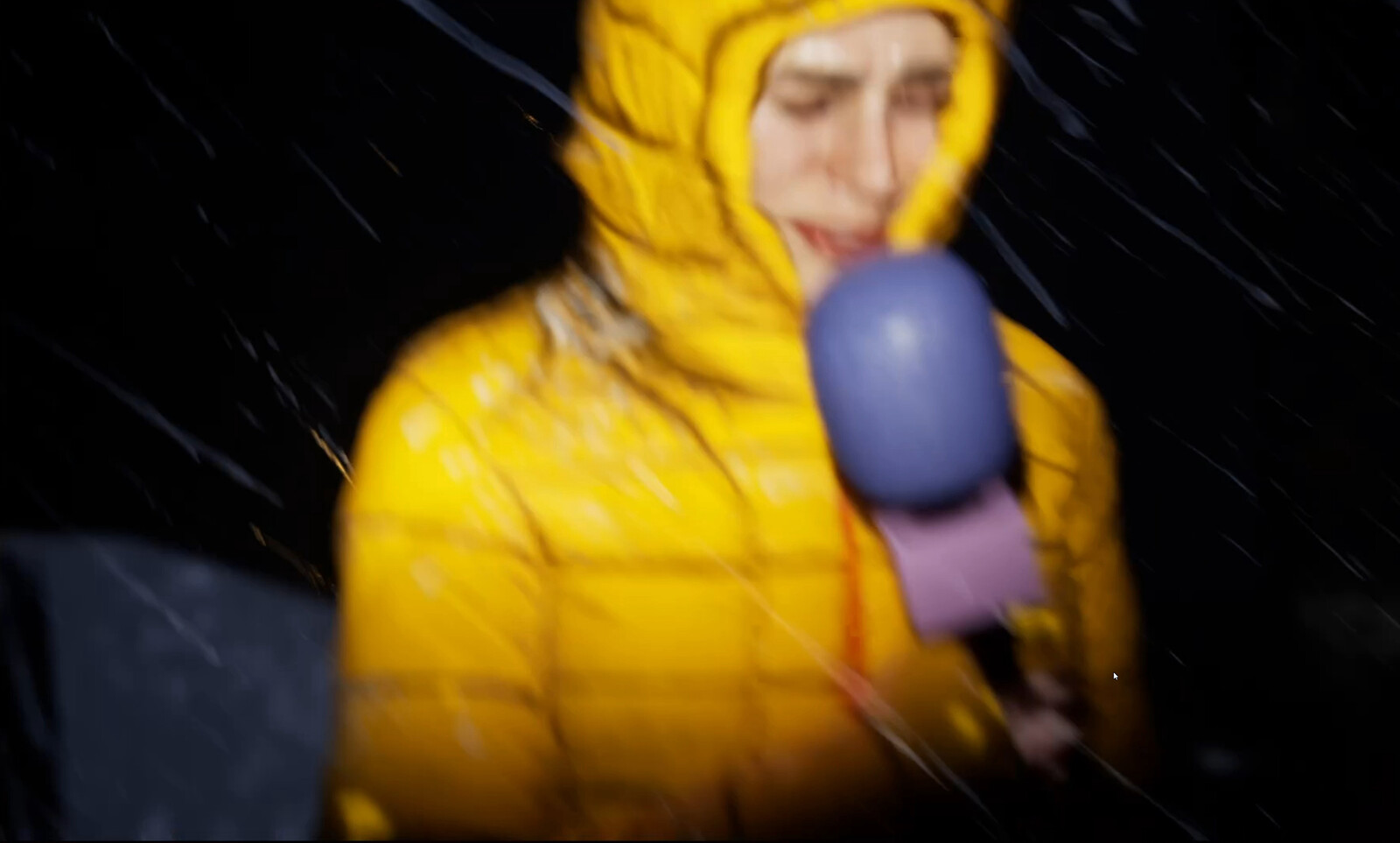

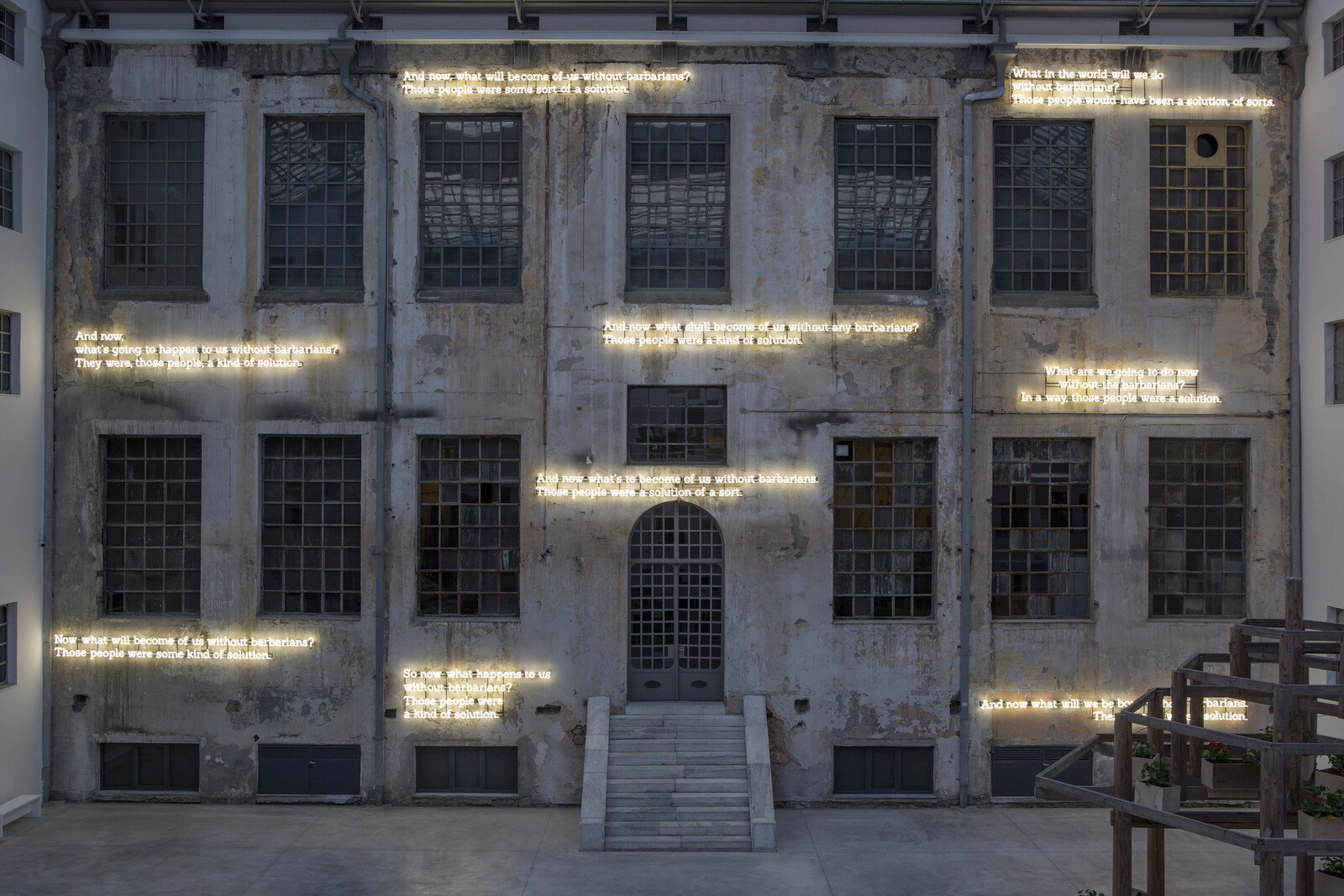

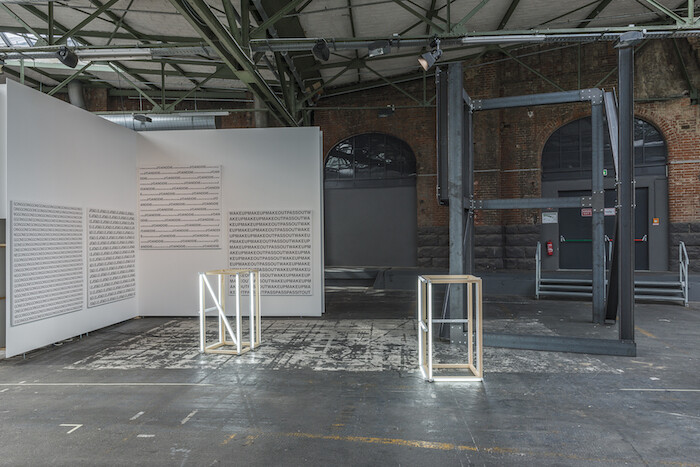

In Germany’s increasingly censorious intellectual climate, Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof staged the Cuban artist Tania Bruguera’s “Where Your Ideas Become Civic Actions (100 Hours Reading The Origins of Totalitarianism)” inside its main hall. This participatory public reading of—and discussion around—Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) was spread across four days, featuring the artist alongside writers such as Masha Gessen and Deborah Feldman, prominent artists in Berlin including Candice Breitz, and people from “the museum’s neighborhood.”

Speakers—mostly solo, sometimes in a trio, and even as a chorus—addressed the audience amid a spare scenography: a single rattan-upholstered rocking chair, illuminated from above by a beam of golden light. Hospital-gray bean bags and cardboard stools were strewn before it, stretching out towards the entrance of the museum and luring visitors into a collectivized consideration of “power and violence, plurality and morality, politics and truth.”

Microphones were connected to a sound system scattered haphazardly around the space, and synchronized with speakers outside the institution facing Invalidenstraße, a thoroughfare leading to Berlin’s central station, a few hundred meters away. Like the work’s title, Bruguera’s sonic gesture felt prescriptive—as if it were the artist’s duty to break Arendt out of the institution and onto the …

February 27, 2024 – Review

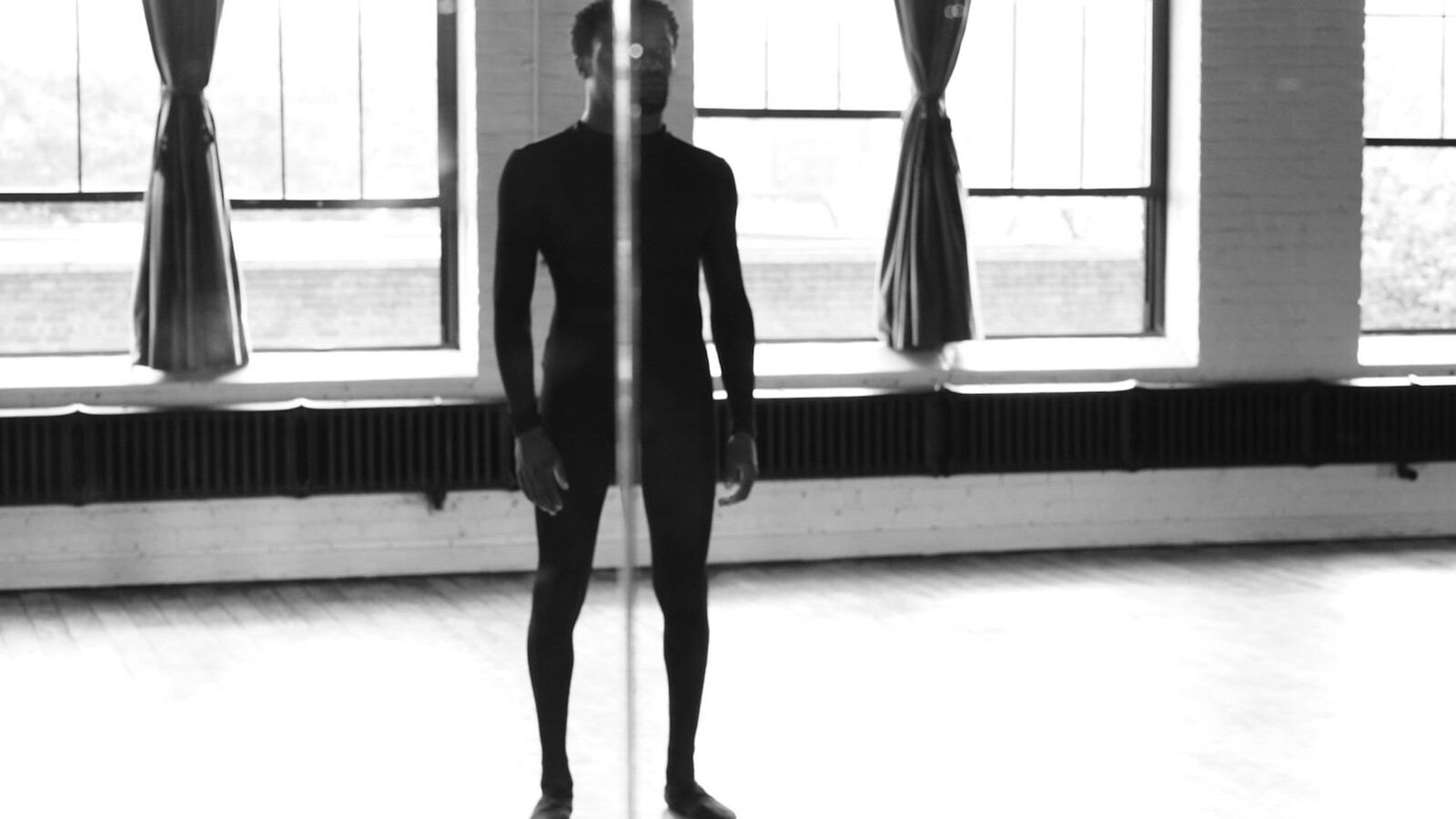

Madeline Hollander’s “Entanglement”

Maddie Hampton

In profile, the six rounded disks at the center of Madeline Hollander’s latest exhibition appear glamorously extraterrestrial, the bright bulbs of the track lighting glinting in their polished chrome surfaces. Arranged in a grid on curved, white pedestals, the satellite-shaped objects are constructed from parabolic mirrors, a hole cut at the top of each to reveal a sinewy figure cast in aluminum, revolving atop a bifurcated circle of colored glass. Based on Hollander’s personalized notation system, specific silhouettes and colors correspond to a precise movement so that, taken in concert, the six figures play out an entire choreography, spinning perpetually in place.

Viewed at the right angle, the maquette doubles, ascending out of the mirror like a ballerina from a jewelry box to create the illusion of a perfect pas de deux—not a limb out of place, nor a posture skipped, as both “dancers” rotate in flawless synchronicity. Titled Entanglement Choreography I-VI (all works 2023), the objects are designed as miniaturized visualizations of quantum entanglement, the theory that two particles can be interdependent, mimicking one another across both space and time, the action of one entirely conditional on that of its partner. Quick and loose with her interpretations of the …

February 23, 2024 – Review

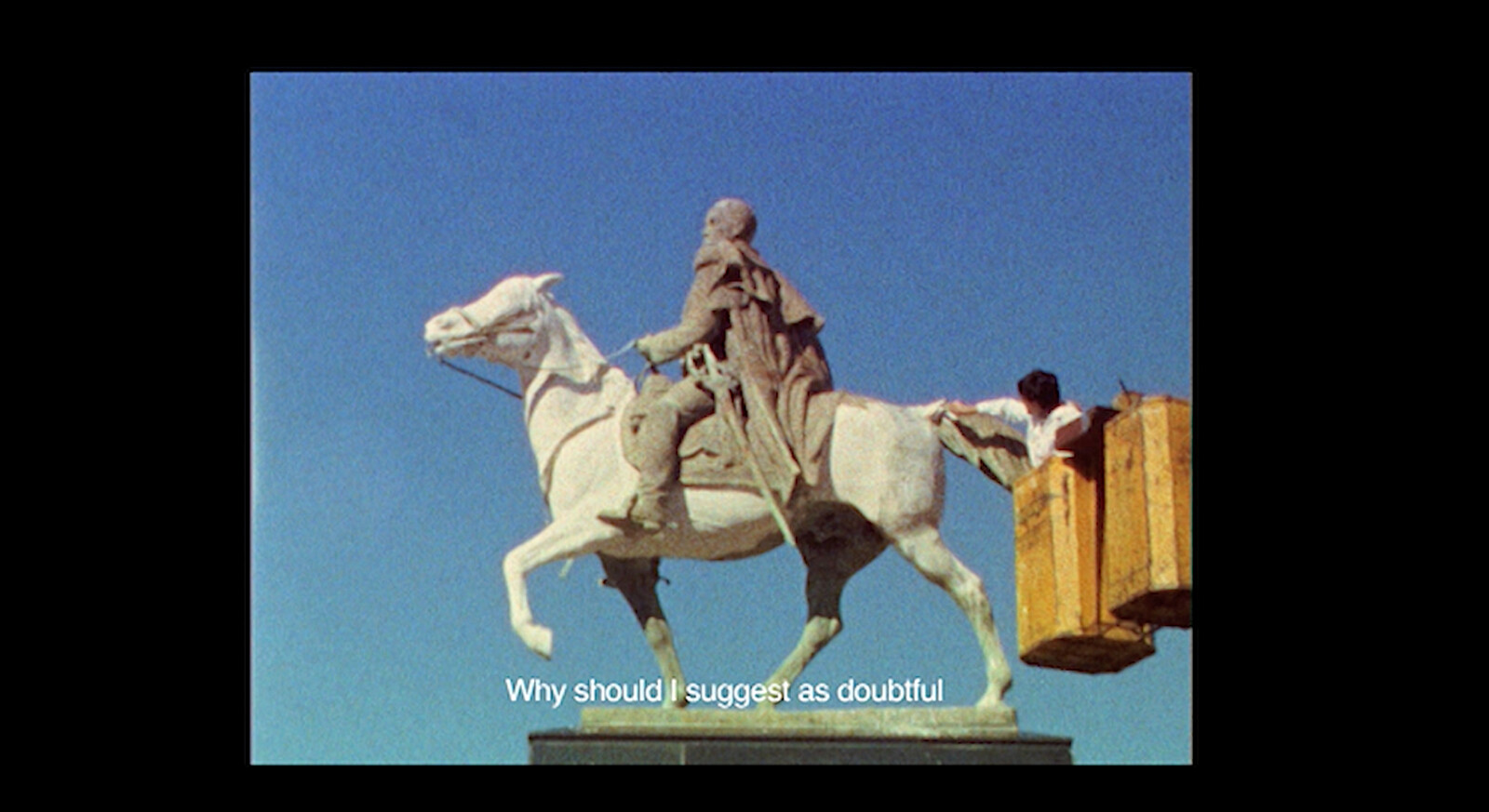

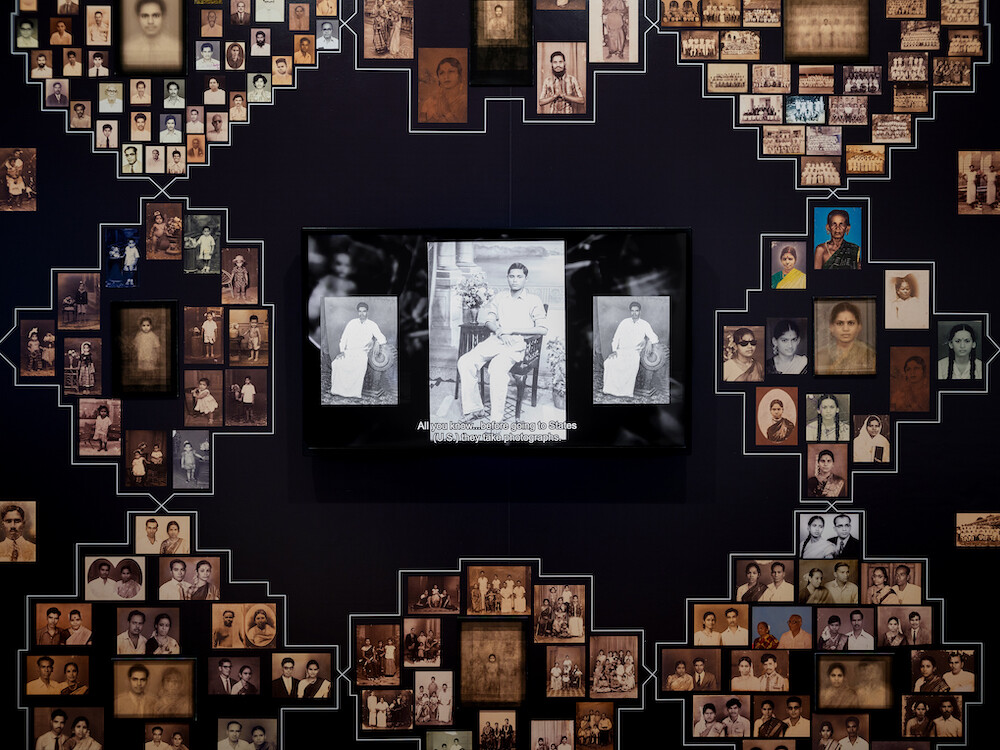

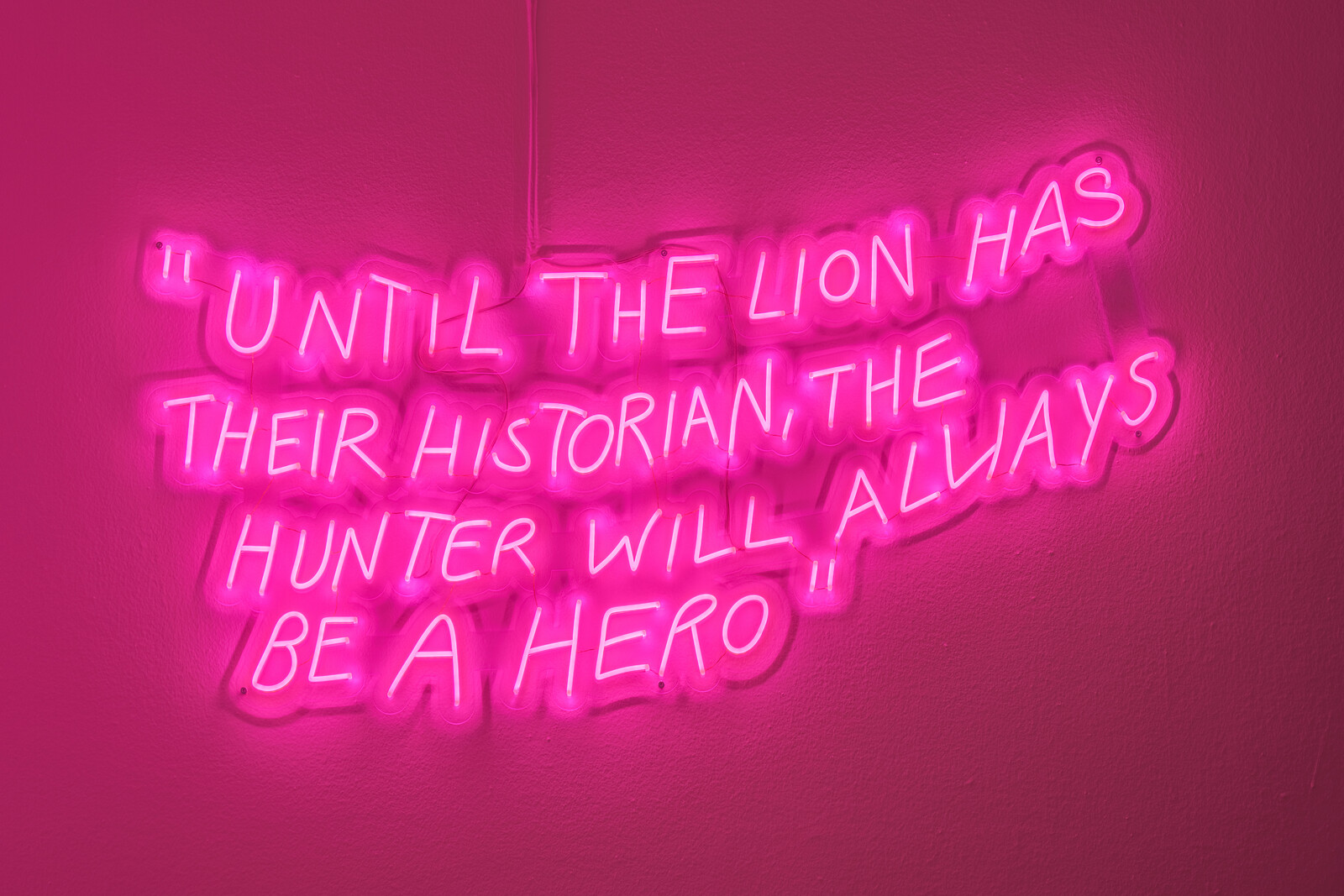

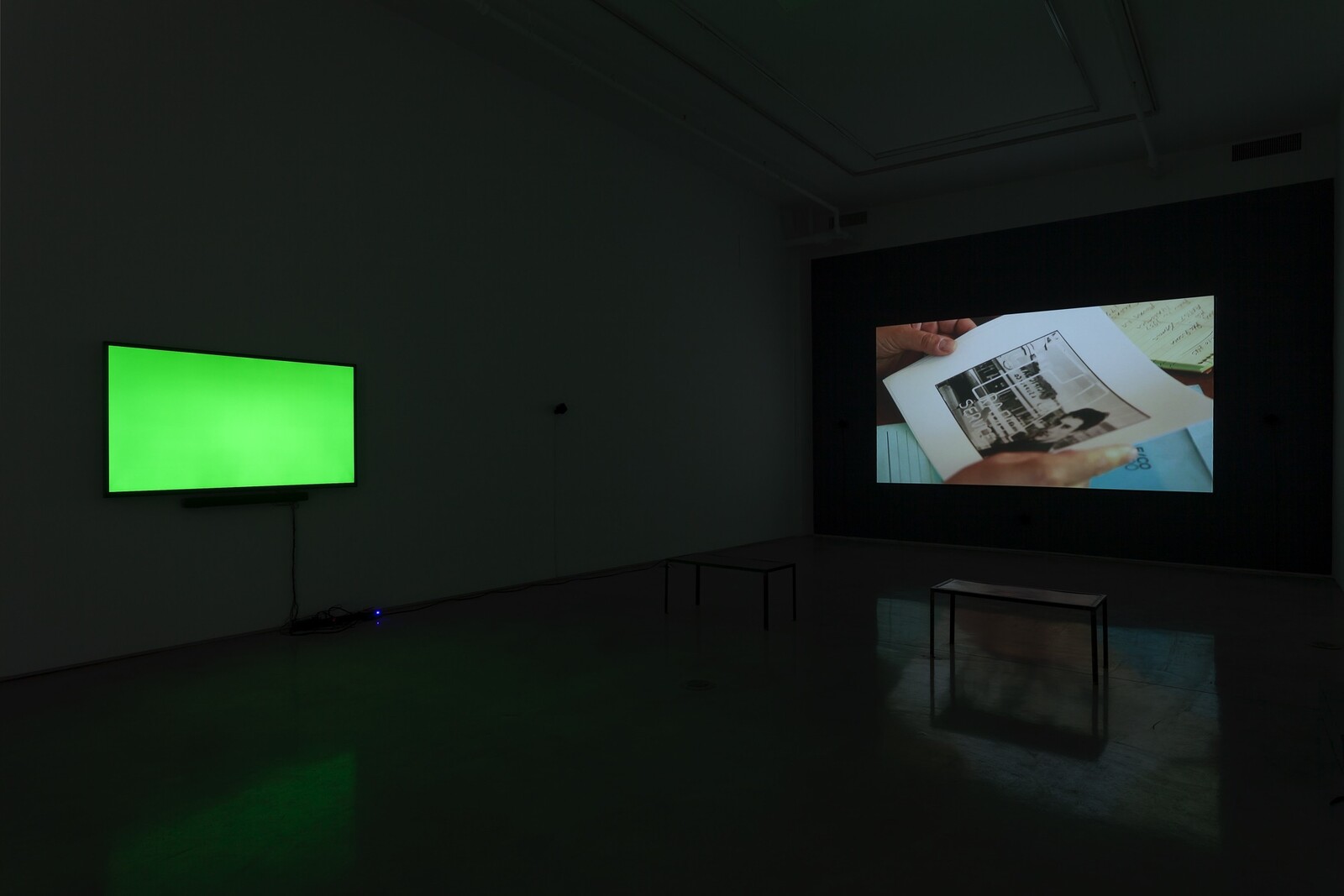

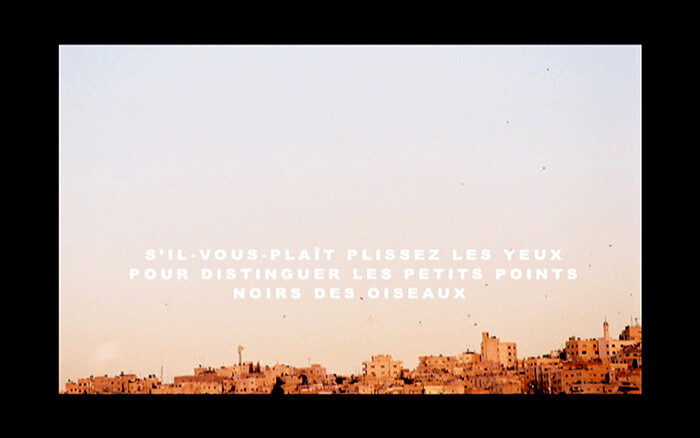

Suneil Sanzgiri’s “Here the Earth Grows Gold”

Phil Coldiron

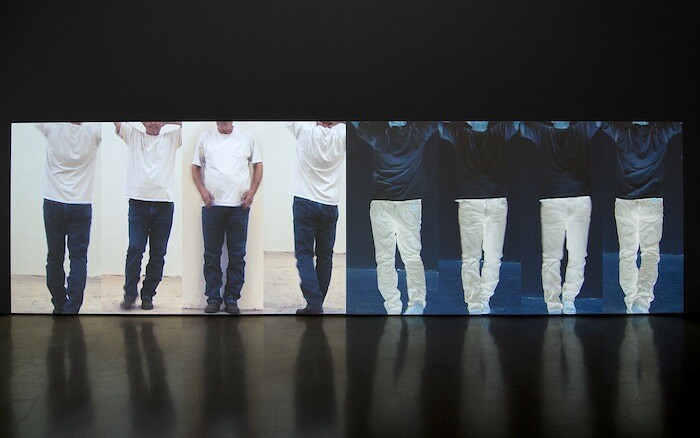

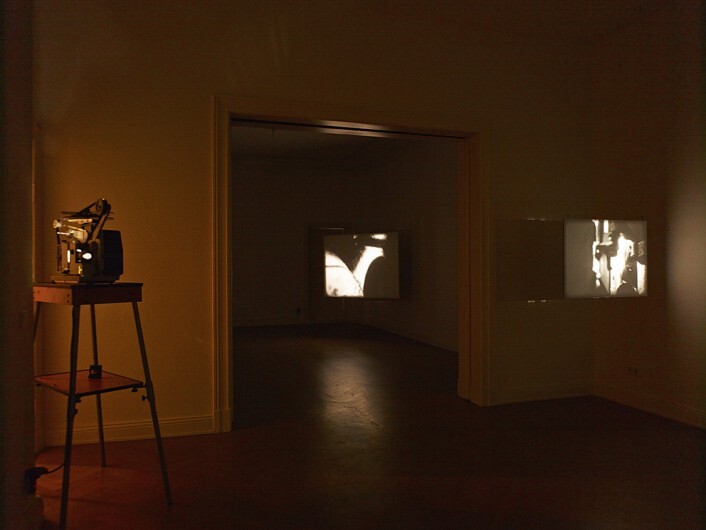

Go past the Tiffany glass, the inventory of deco design and the wing of feminist art that still bears the name Sackler, and finally, tucked away, you’ll find a small enclave of two rooms comprising Suneil Sanzgiri’s solo institutional debut, “Here the Earth Grows Gold.” The smaller of these galleries contains: a sculpture, Red Clay, Stretched Water (Return to the Source) (all works 2023), a kind of provisional hut built of black bamboo and printed images; a minute-long loop of 16mm film, My Memory Is Again in the Way of Your History (After Agha Shahid Ali), in which a digitally-animated banner reading “Your History Gets In The Way Of My Memory” flutters atop waves; and quite a lot of wall text (the one written by the artist himself, demanding that the Brooklyn Museum divest itself of various ill-gotten items in its collection, might reasonably be taken as the show’s fourth work). Moving through a curtain to the centerpiece, the digital double-projection Two Refusals (Would We Recognize Ourselves Unbroken?), maybe the first thing you notice is the gap between its screens: each canted slightly off an unseen wall, they funnel vision to the six inches or so of space between them.

…

February 22, 2024 – Review

Jane Jin Kaisen’s “Halmang”

Dylan Huw

A group of elderly women labor silently, weaving and draping long sheets of white cotton around an islet of black volcanic rock. The twelve-minute film installation’s supplementary materials explain that these women have spent much of their lives working together as haenyeo—an occupation dating back centuries, in which women freedive to harvest seafood for their families on Jeju Island, south of the Korean Peninsula—and that this precise setting is one of shamanic significance, associated with the goddess of wind who gives the film its title, Halmang (2023). The Jeju-born, Denmark-based artist’s patiently observational study of these “women of the sea” emphasizes their status as workers by foregrounding, in lingering close-ups, their aged, scarred faces and hands as continuous with the aged, scarred rock. A soundtrack of crushing waves lulls the viewer, until the film’s confronting climactic image: the islet depeopled and draped in the white cotton. This land, born from geological shock and host to centuries of politically contested narrative, will outlive us all.

Halmang gives this tightly focused exhibition at Manchester’s esea contemporary its title and centerpiece. With a refreshing formal lucidity, it literalizes themes of familial and geopolitical ties that have been central to Kaisen’s work in film …

February 21, 2024 – Review

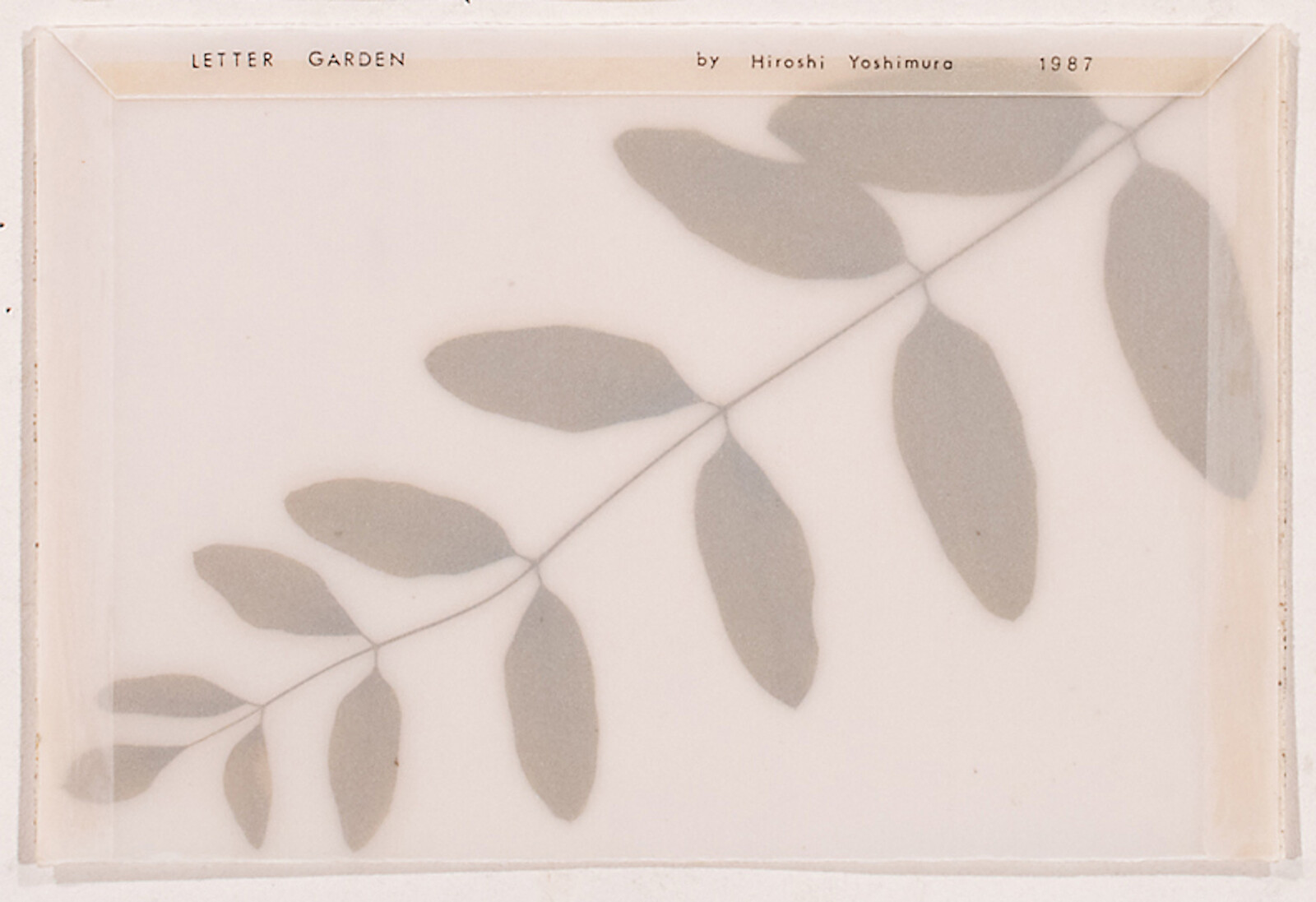

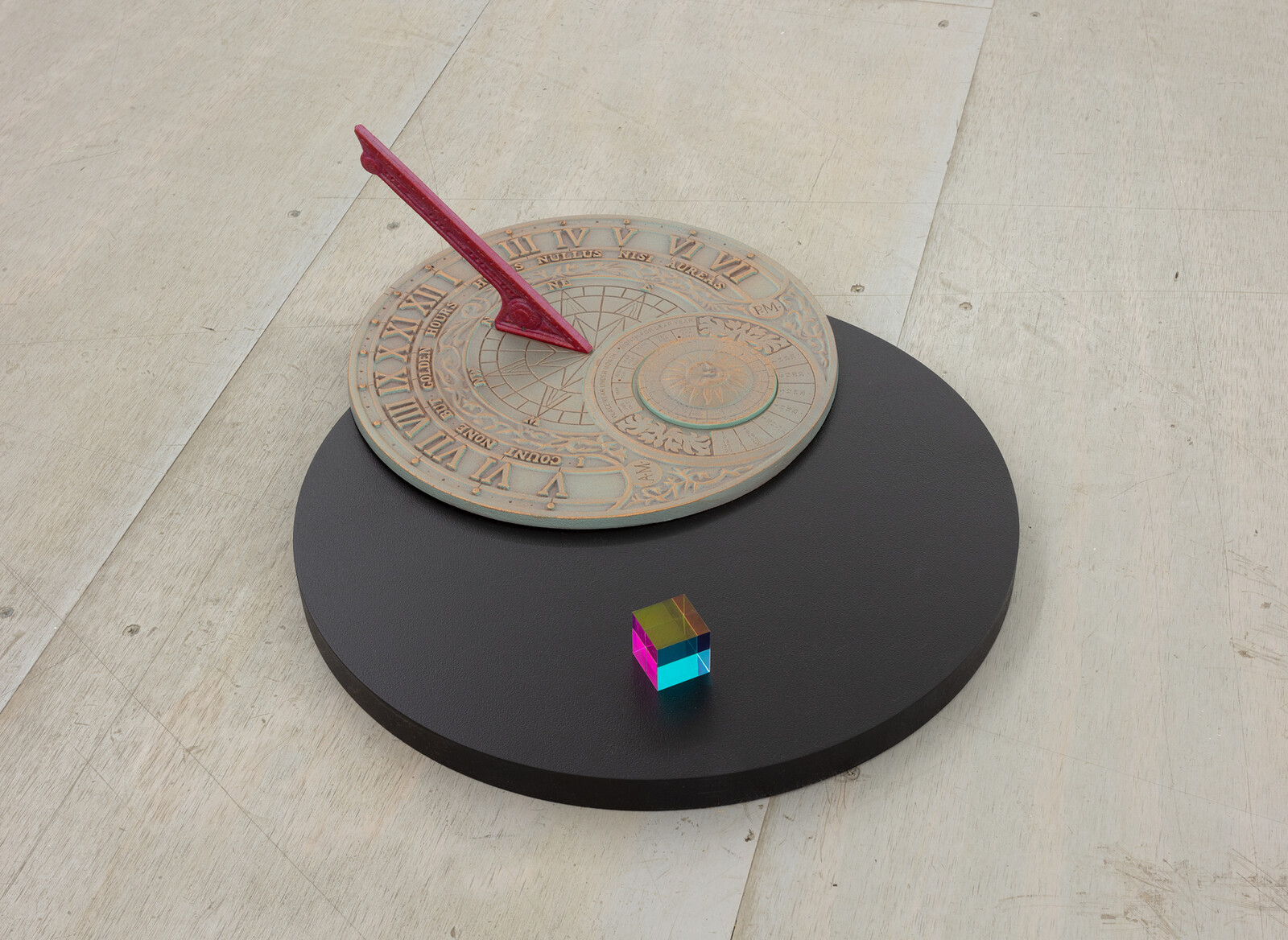

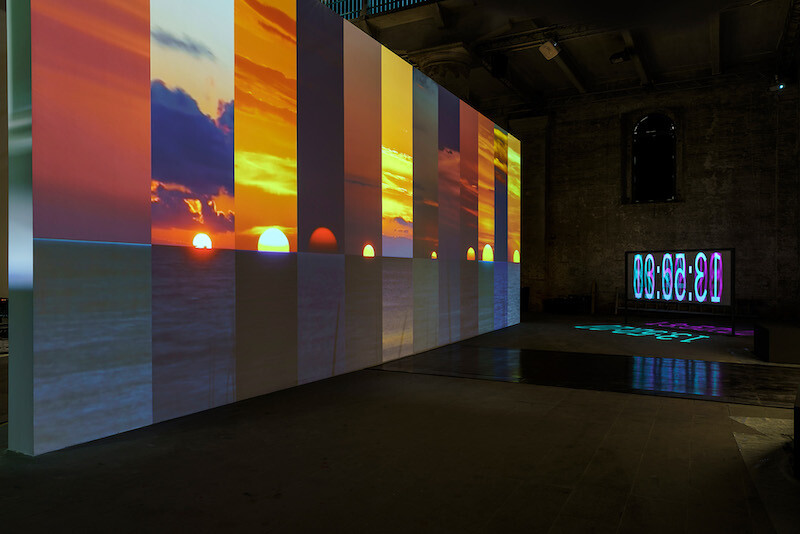

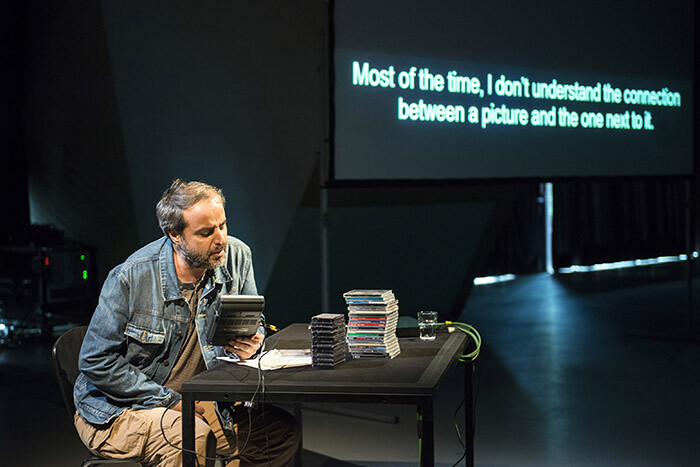

Ho Tzu Nyen’s “Time & the Tiger”

Adeline Chia

Meditations on the nature of temporality abound in Ho Tzu Nyen’s latest video work, T for Time (2023–). We have explainers on timekeeping traditions in the East and West; a vignette about a man who maintains Singapore’s oldest public clock; the origins of Greenwich Mean Time; metaphysical musings on non-linear time (“time conceived as a viscous fluid… it does not pass and has no rim… it pools”). Accompanying most of these are digital animations that sometimes illustrate the concepts—like imagery of a molting ouroboros—and visuals with less obvious connections to the theme, such as recurring scenes of political protest and incarceration. Most of the text is sung by a male narrator in seemingly improvised melodies. Content, which is shuffled by an algorithm, starts to repeat only about seventy-five edifying minutes in. I was intrigued, stimulated and entertained, but couldn’t escape the feeling of being lectured to. This has something to do with the video’s heavy reliance on text: this work narrates itself.

Ho’s self-narrating, self-theorizing, and sometimes even self-interpreting practice involves a thorough immersion in a range of research topics, resulting in a cathartic showing and telling that has become his signature style. “Time & the Tiger”, a mid-career survey …

February 15, 2024 – Review

Pedro Lasch’s “Entre líneas / Between the Lines”

Mariana Fernández

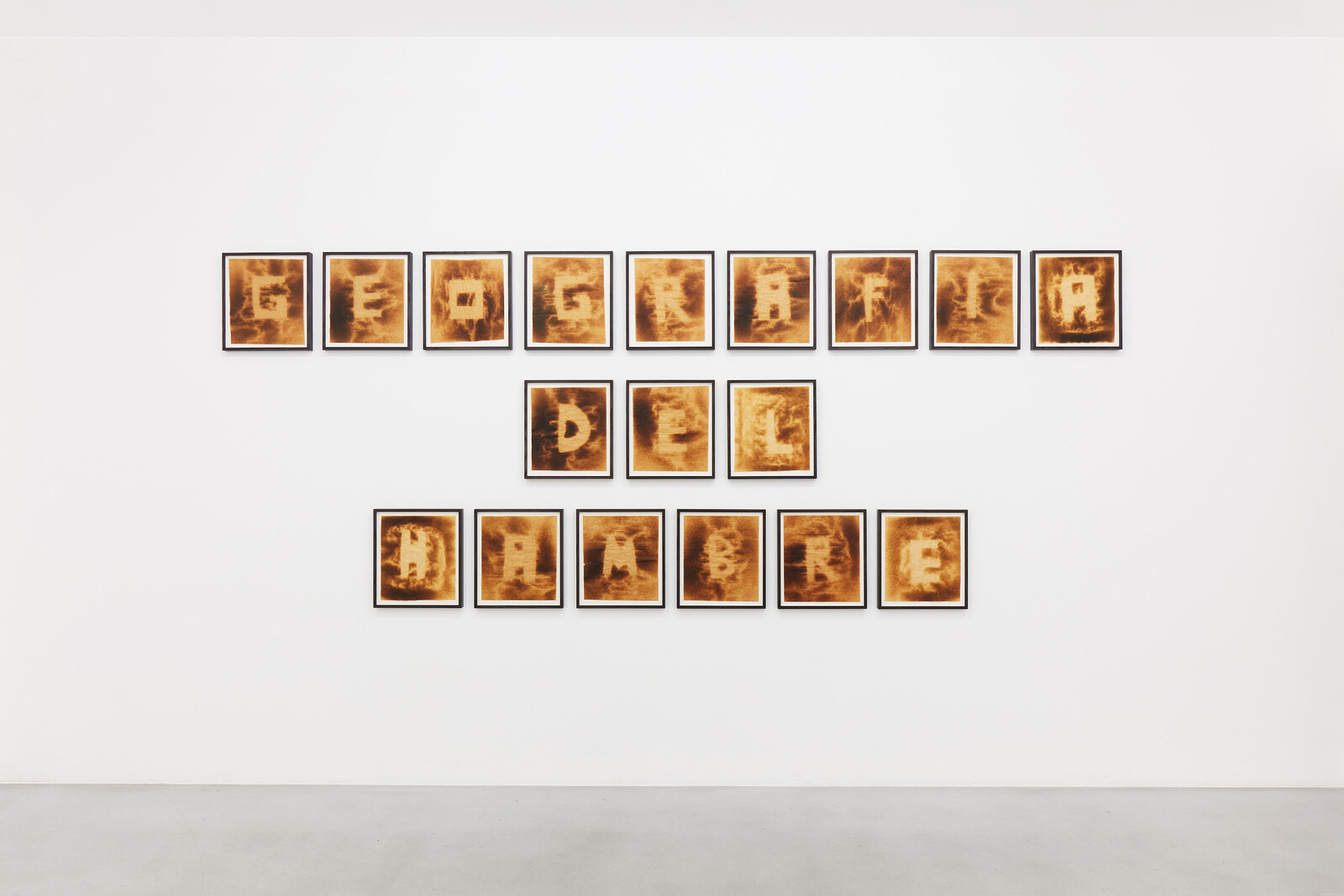

Pedro Lasch’s mid-career survey at Laboratorio Arte Alameda begins with a painting—the ultra-deadpan McSickle, grande no. 1 (2003)—depicting a yellow hammer and sickle fusing with the “M” of McDonald’s on a red background. These two colors also happen to make up the Chinese flag. The painting exemplifies the multiple layers of Lasch’s practice: the artist is best known not so much for making things as for creating opportunities for social encounter and collaboration through his roles as an activist, educator (he teaches at Duke and is the director of its FHI Social Practice Lab), and cultural organizer (with the collective 16 Beaver). Yet the thematic survey “Pedro Lasch: Entre líneas / Between the Lines” manages to avoid the document-heavy trappings into which displays of socially engaged art sometimes fall because of how well Lasch’s social practice translates into objecthood. The survey shows that whether in the form of painting, installation, props, performance scores, or game instructions, Lasch has long been thinking about the tensions between colonialism and cultural exchange, and using art as an entry point into public engagement with a decolonial agenda.

These themes are on full display in the mural painted on the back wall of the main …

February 13, 2024 – Review

Hanan Benammar’s “The Soil Is Fertile But For A Distant Seed”

Natasha Marie Llorens

Here lies idealism. This my first impression of a marble tombstone that marks the entrance to the second floor of Bomuldsfabriken Kunsthall. Instead of a name or a set of dates, it bears the words awareness, insight, and knowledge in Norwegian. Hanan Benammar’s sculpture ERKJENNELSE, INNSIKT, KUNNSKAP (2020), re-stages a comment by an established historian on NRK (Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation) regarding a previous work by the artist, Antiphony (2019), in which Benammar set up a calling service that put visitors in touch with strangers to discuss a range of concepts, such as emptiness, chaos, silence, violence, boundaries, and doubt, staging exploratory and open-ended one-on-one discussions. The art historian cited in the more recent sculpture dismissed Antiphony as lacking any significant “awareness, insight, or knowledge.” Those qualities were properly represented by figurative marble sculpture, in this historian’s view, because “marble is art with a capital A.”

It is tempting to dismiss the notion that art must be made in marble to represent insight as reactionary provincialism, an inconsequential view in the broader context of geo-political crisis. Yet such dismissals echo the ways in which the conspiratorial claims emanating from what Naomi Klein, in her 2023 book Doppelganger, dubbed the “Mirror World” …

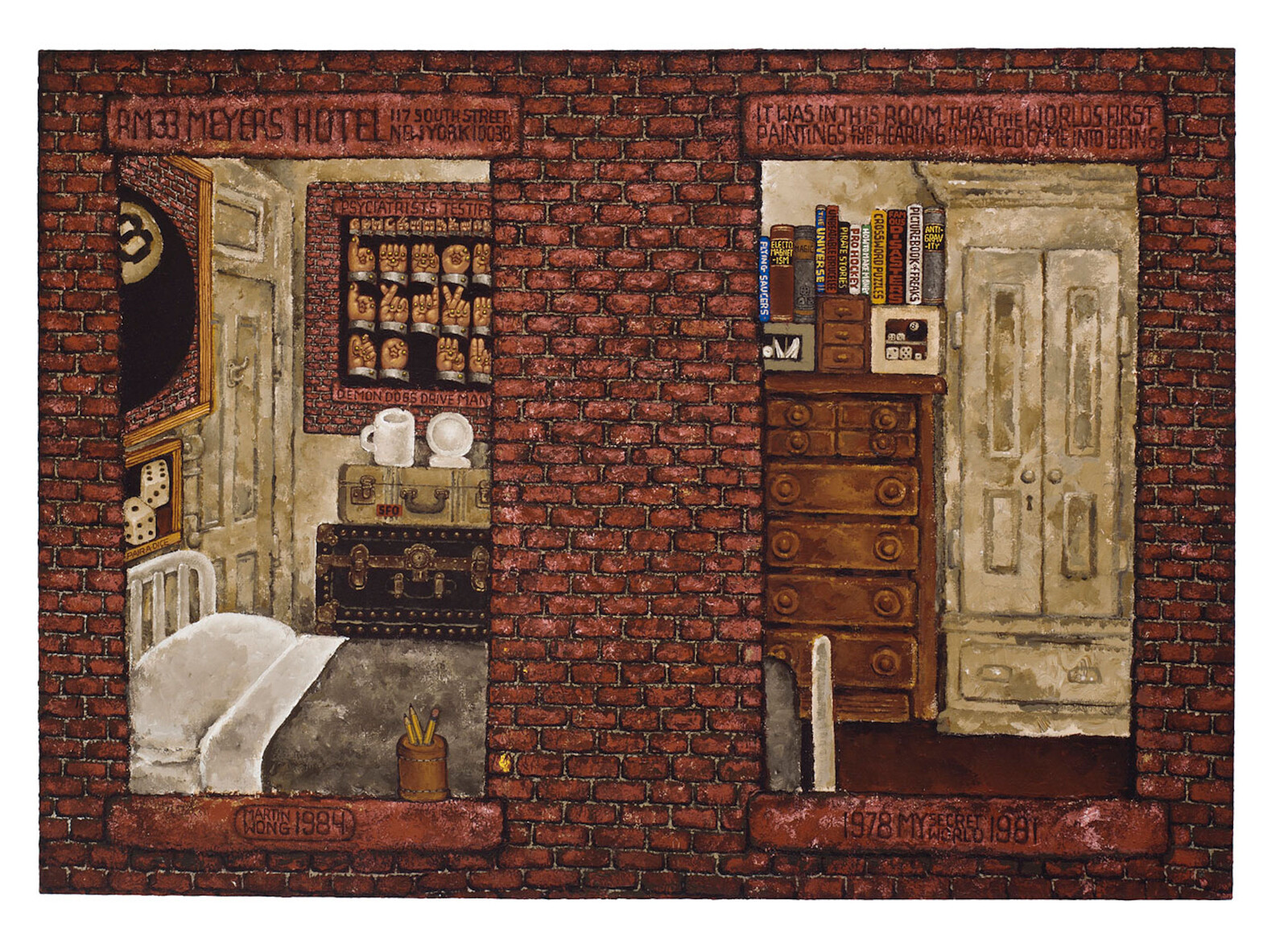

February 12, 2024 – Review

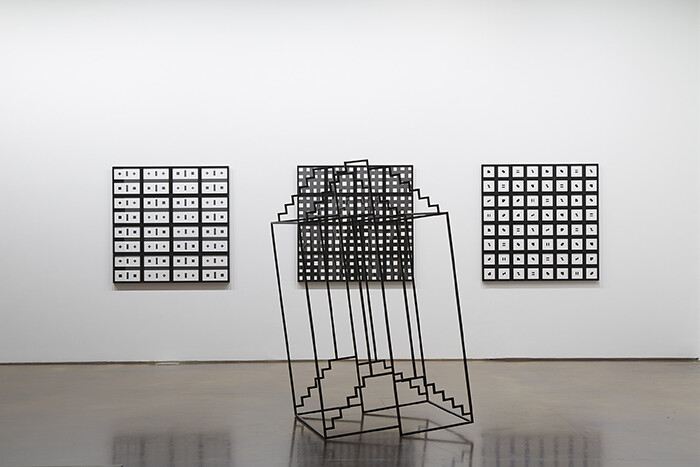

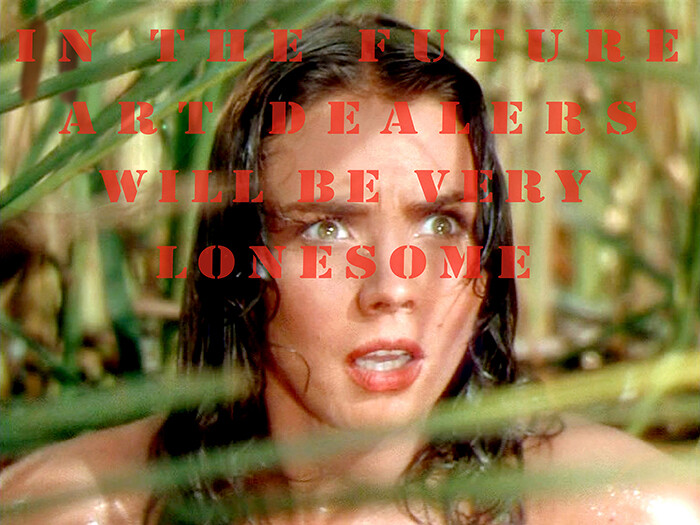

Kwan Sheung Chi’s “Not retrospective”

Stephanie Bailey

Everything about Kwan Sheung Chi feels elusive, even when he’s telling you about himself. Take the artist’s press release for “Not retrospective,” which includes “less [sic] than 40 recent and previous sculptures, photographs and videos.” A biography cites two solo shows Kwan staged in 2002, one year before he graduated from the Chinese University of Hong Kong and one year after his joint funeral-as-exhibition with artist Chow Chun Fai, when they burned their art. The first is “A Retrospective of Kwan Sheung Chi” at Hong Kong’s 1a space, for which there is scant online record. The second is “Kwan Sheung Chi Touring Series Exhibitions,” described as ten “major” exhibitions at different Hong Kong venues that apparently involved Kwan photographing himself in each site.

Kwan has long resisted the market’s tendency to commodify artists by leaning into commodification as a systematic process that resonates with the conceptual grid—an approach that couches critical gestures within layers of satire. Divided into three sections, “Not retrospective” stages this sleight of hand. It begins with a small white cube crudely built from wooden boards like a stage set, where a trio of pennant banners strung up at the entrance made from dust jackets for Marx’s …

February 9, 2024 – Review

Astrid Klein

Xenia Benivolski

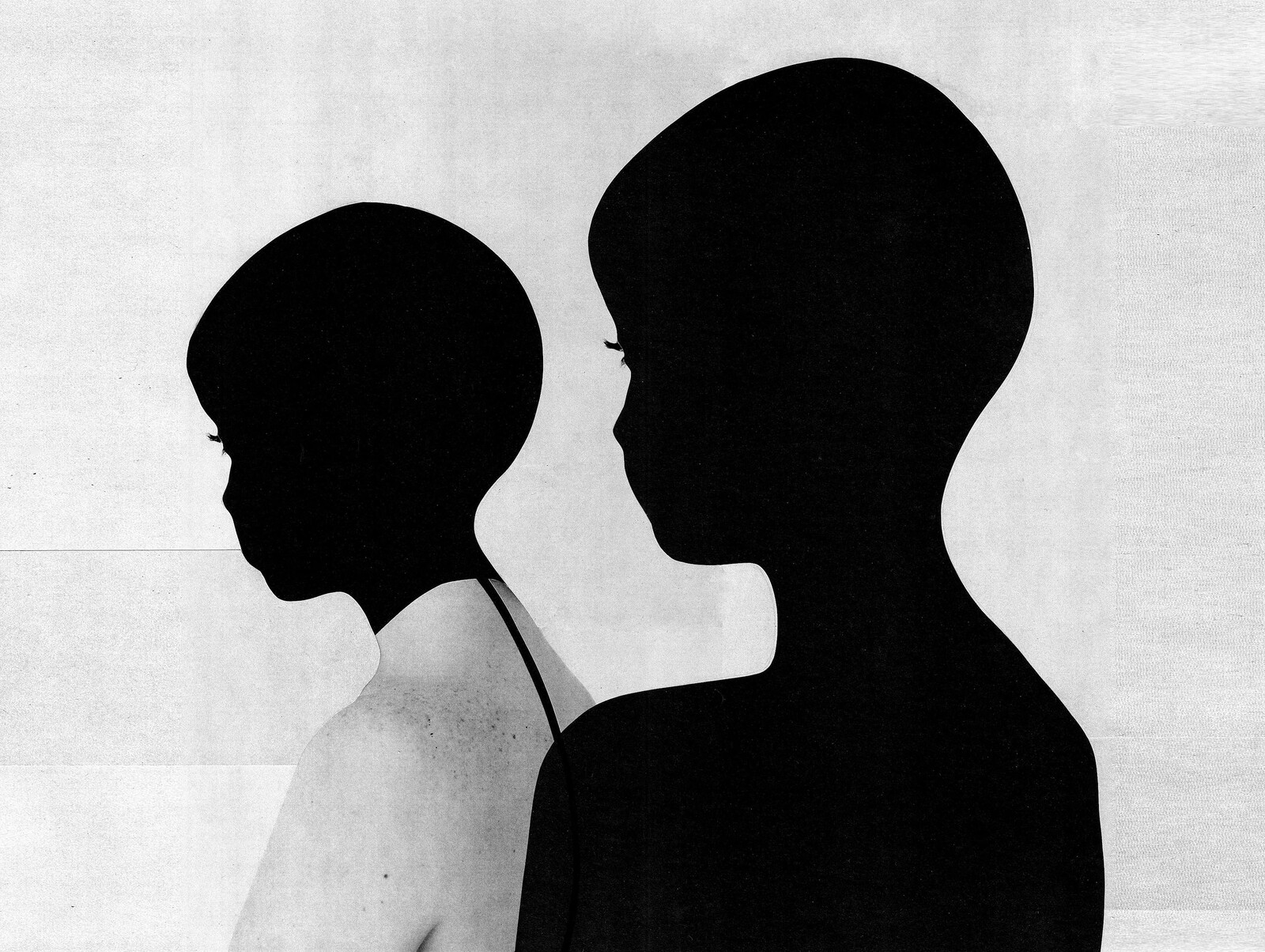

Astrid Klein’s photowork Untitled (Je ne parle pas,…) (1979) presents two cut-out images of Brigitte Bardot—posing in a baby doll dress and, again, coquettishly looking back over her shoulder. In broken, typewritten French and English are the words “je ne parle pas, je ne pense rien” (“I don’t speak, I don’t think”) and “to paint my life, to paint my life, so many ways.” It’s a fitting prelude to this exhibition, which is something of a house of mirrors. Trapped behind the museum glass, like sexy cats in apartment windows, large photographic works fill the walls, each featuring a beautiful woman while slyly reflecting the viewer. In Untitled (la sans couleur…) (1979), a reclining woman awkwardly turns her head to look at me with an enigmatic smile. Loosely draped in a sheet on an unmade bed in the dark, she is a body in waiting. These gazes are not exactly inviting; if anything, they somehow lack emotion, as the title reflects: “masks without color.” But there is something cool, even powerful, about their magnetic resignation. Like several in the show, the image is arranged with visible marker framing and taped sections, giving the impression that this composition sets the stage …

February 8, 2024 – Review

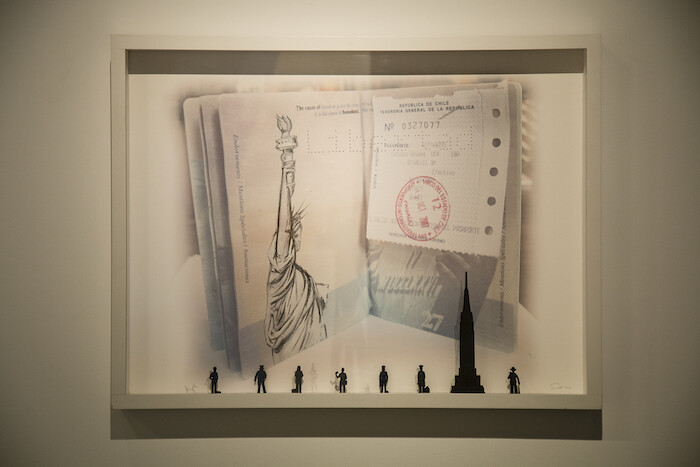

Alfredo Jaar’s “El Lado Oscuro de la Luna”

Juan José Santos

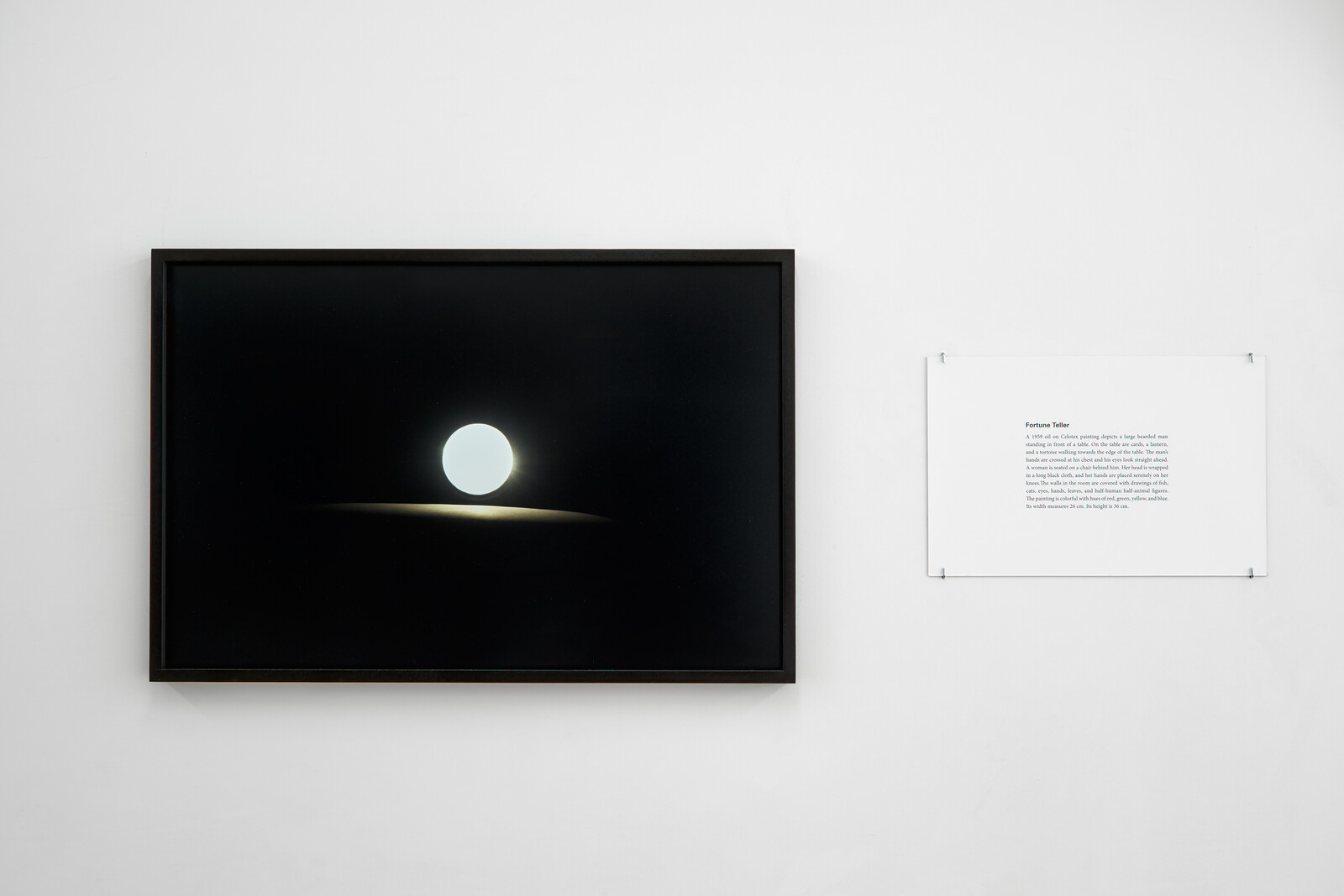

Is that hysterical laughter? And are those accelerated heartbeats the phantasmagoric echoes of Chile, circa 1973? These sounds are not leaking into the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes but are rather the reverberations of an album released that same year: Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, which plays on a loop in this exhibition of works made by Alfredo Jaar between 1974 and ’81. Jaar was seventeen when General Pinochet’s coup d’état tore his country apart, and the young artist sought refuge in this soundtrack of madness and despair.

Pink Floyd’s front-man and lyricist Roger Waters last year released The Dark Side of the Moon Redux, a “reimagining” of the album from which this retrospective takes its title. Where he chose to replace David Gilmour’s guitar solos with homiletic spoken word, curator Pablo Chiuminatto has gone the other way. Rather than over-explain, Chiuminatto’s approach offers little contextualization or research for Jaar’s early works, which mark a turning point in the career of one of Latin America’s most significant artists.

The restrained curation lends the show a provisional feel, an analysis of sketches by an obsessive apprentice. These range from Jaar’s initial experiments with dry-transfer lettering methods, such …

February 2, 2024 – Review

Deimantas Narkevičius’s “The Fifer”

Michael Kurtz

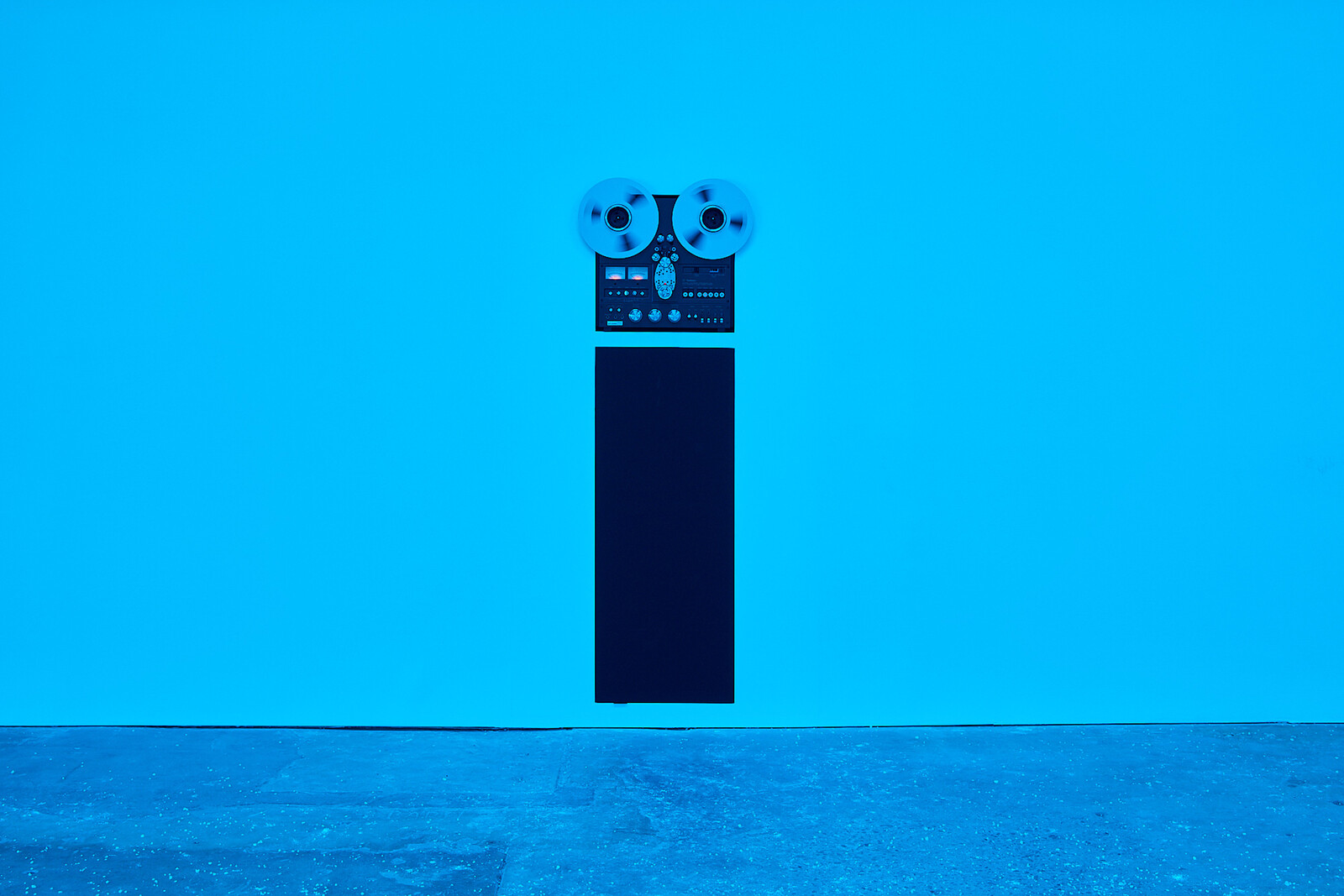

The centerpiece of Deimantas Narkevičius’s current exhibition at Maureen Paley is a holographic screen—a small block of glass on a sleek metal shelf. A nightingale appears in the glass and lands on a branch that hangs there, while audio plays of a flute mimicking birdsong in sync with the movements of its beak. It flies out of view again and then returns, left and right, left and right. On an adjacent wall is another branch of sorts—a bark-like bronze cast of the cavities inside a flute—and nearby hang two small black-and-white images: a 1920s photograph from the Lithuanian State Archive of a soldier playing the flute by a window and a digital recreation of the same scene from directly outside the building. This perplexing constellation of objects is named after the shadowy figure in the photograph, The Fifer (2019).

Holography represents the height of illusionism, elaborately conjuring animated three-dimensional images. But the nightingale’s restless movement in and out of frame continually calls attention to the screen’s edges, where the projection falters and the empty glass block becomes visible. The illusion is further ruptured by the flutist’s birdsong which, isolated from any ambient sound, is unconvincing. Each item here performs a …

January 31, 2024 – Review

Naoki Sutter-Shudo’s “End of Thinking Capacity”

Gracie Hadland

Naoki Sutter-Shudo addresses the current critical landscape with a series of seven “Critical Figures” and twelve paintings. Installed in only one half of the gallery, the audience of figurative sculptures faces a wall on which is hung a row of large graphic canvasses. Each is adorned with a formal accessory made of flimsy material: a wire twist-tie shaped into a tie, a fake lettuce hat, a shirt made of bubble wrap or a plastic bag. The figures’ apparent attempts to present as professional are rendered ridiculous by the nature of their clothing. They look as though they’re dressed for a nineteenth-century salon—complete with bonnets, big collars, and ties—rather than a contemporary art gallery. Each figure’s body has an intricately constructed apparatus holding a wind-up metronome with a bell (some in 3/4 time, others in 1/4 time) and has a unique look, height, and facial expression tending towards the bizarre—one has three heads, for example.

The viewer is able to wind up the “critics,” letting them spin their wheels while looking around the show. The result is a rhythmic kind of chatter punctuated with the ding of a bell, as if to signal a lightbulb moment. Sitting atop stacks of white …

January 26, 2024 – Review

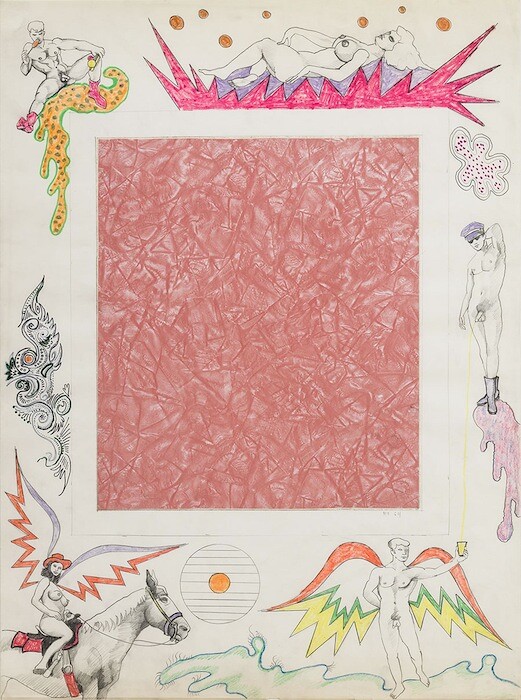

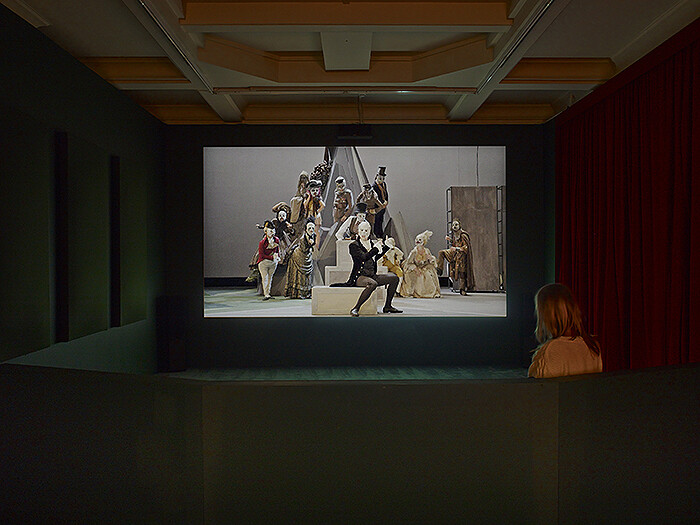

Jan Van Imschoot’s “The End Is Never Near”

Jörg Heiser

Belgian painter Jan Van Imschoot’s first major retrospective—the show that should gain him the belated international recognition his work deserves—spans four decades, seven rooms, more than eighty paintings, a bar, and a small cinema. And it starts with a landscape-format painting sitting smack across the entrance. A cherub or cupid, though with no wings, painted much larger than life, reclines against an indistinct, darkly looming background. The little big fellow has apparently nodded off, his nipples, shiny belly bottom, and tiny weenie standing out like bumps and craters on the surface of a full moon. The motif and the title Amore Dormiente (2018) pay direct homage to Caravaggio’s Sleeping Cupid (1608), a small painting at home in the Uffizi.

But homage immediately turns into, well, what? Parody? Grotesque exaggeration? In this adaptation, cupid’s face is wreathed by a shock of auburn hair, a rather adult skyward nose, sagging cheeks, and eyes swollen half-shut, like an old drunk’s. Instead of a bow and arrow in his left hand, in his right he holds a handwritten letter in French, signed by van Imschoot, which translates as: “Aposematism in painting: on linguistic confusions and the mimesis of lies, or the challenge of the …

January 25, 2024 – Review

“As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories”

Olexii Kuchanskyi

Against a backdrop of constant territorial changes in the former Soviet countries and the ongoing war in Ukraine, “As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories” explores the “geopoetics of North Eurasia.” The term denotes heterogeneous, yet tightly interconnected, political and cultural contexts under oppressive regimes, ranging from the Russian Empire to contemporary Russian imperialism via Soviet colonialism. Framed in the handout by HKW’s director, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, as a way of “being and seeing the world through the prism of the Global East,” the show tries to avoid any “totalizing vision” in favor of multiple subjectivities and geographies.

To achieve this, the show’s curators—Cosmin Costinaș, Iaroslav Volovod, Nikolay Karabinovych, Saodat Ismailova, and Kimberly St. Julian-Varnon—have scattered the artworks across the museum in a way that foregrounds their discreteness, each piece separately lit and surrounded by empty space. Stories of colonialism, resistance, and artistic experimentation are encapsulated in these “monads,” yet the aversion to a “totalizing vision” extends to the bewildering absence of wall texts from the galleries (viewers hoping for context must flip through the handbook, which lacks a general plan of the show, to find a work description).

The exhibition’s main space is filled …

January 22, 2024 – Review

“Self-Determination: A Global Perspective”

Judith Wilkinson

“Everyone has the right to a nationality,” states article 15 of the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” (1948) and “no one shall be deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.” As part of “Self-Determination: A Global Perspective,” Banu Çennetoğlu has filled the Irish Museum of Modern Art’s East Wing Gallery with three gigantic bouquets of gold helium letter balloons. Each bouquet, a mass of oversized jumbled letters, spells out a different article from the declaration. Throughout the course of the exhibition the balloons that make up right? (2022–ongoing) will deflate, lowering to the ground, until nothing remains but their empty carcasses.

An initiative of Annie Fletcher, IMMA’s director since 2019, “Self-Determination” explores the establishment of new post-World War I nation-states—including Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Poland, Ukraine, Turkey, Egypt, and Ireland itself—focusing on the role that art and artists played in statecraft and the formation of the national imagination. The site of the exhibition, the Royal Hospital Kilmainham (built in 1684 as a home for retired British soldiers), holds significance in the construction of the Irish nation. It was considered as a potential headquarters for Oíreachtas Shaorstát Éireann, the newly established government of the Irish Free State …

January 18, 2024 – Review

Shubigi Rao’s “These Petrified Paths”

Katherine C. M. Adams

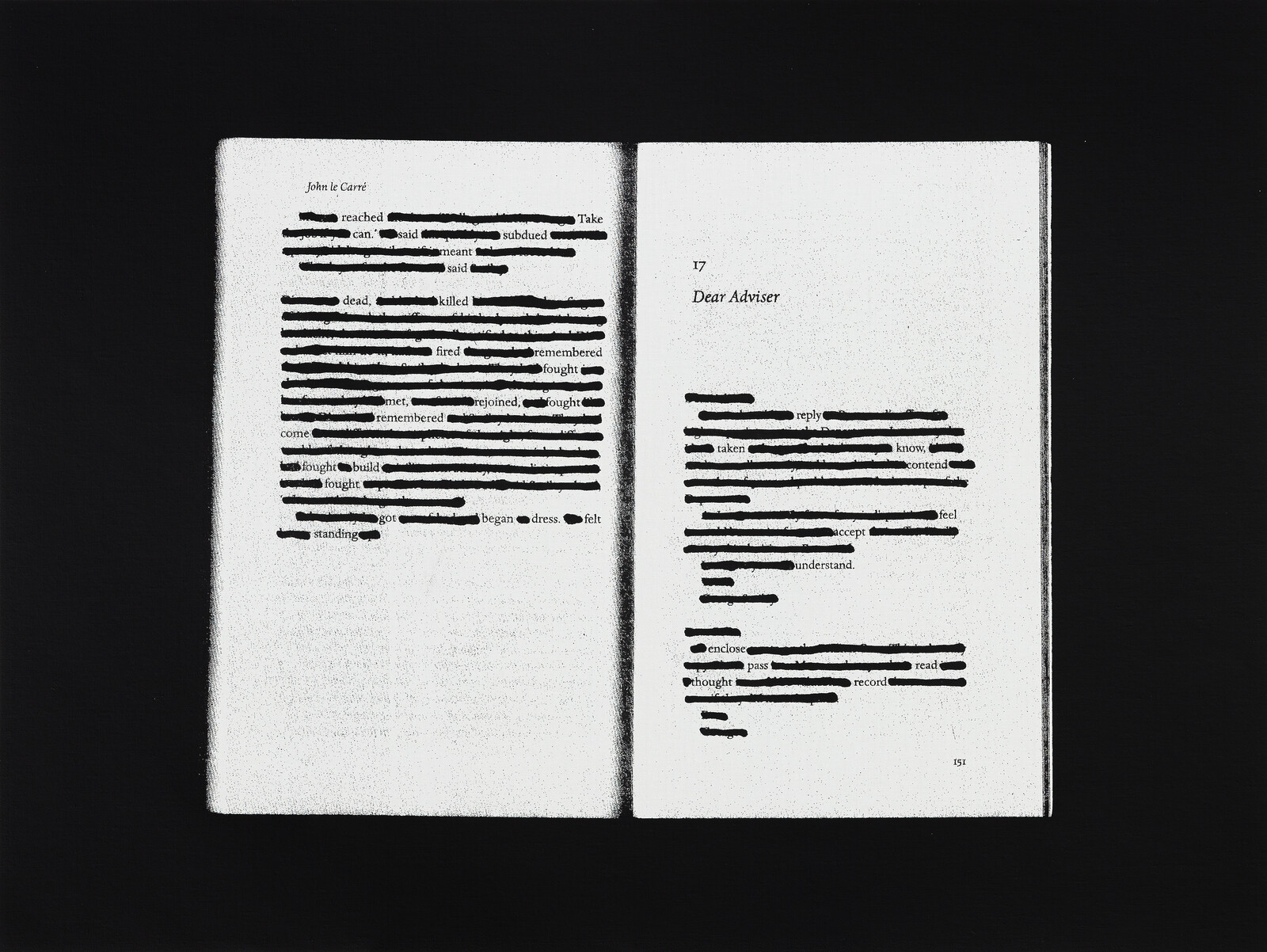

In Shubigi Rao’s new film These Petrified Paths (2023), censorship is always tied to the threat of repressive territorialization. Early on, we are introduced to a “former professor of Russian literature, now beekeeper on the side of the road to Daliyan” in Turkey, who embodies a theme of the exhibition at large: how a struggle over literature and written culture has led to a fight over ecology, terrain, and the right to live freely on one’s Indigenous land. In the film, this process is inflected by the historical function of Armenian literature as a tool of nation-building, forging claims to place for a people often on the verge of statelessness. As one featured subject remarks of the region’s history, the Armenian genocide is also “cultural genocide.”

These Petrified Paths details (among other threads) the lengths to which Armenian intellectuals have gone to preserve their heritage: one participant describes how an elder member of the community buried his books in the ground, with the intent that they be dug up only upon the retreat of repressive state forces. Toward the end of the film, an interlocutor alludes pessimistically to the contemporary Armenian government’s attempts to “sell off” part of the country …

January 16, 2024 – Review

“Intimate confession is a project”

Valentin Diaconov

Curated by Houston-born curator Jennifer Teets, “Intimate confession is a project” looks at what her academic inspirations—Lauren Berlant, Ara Wilson, Kai Bosworth—have called “affective infrastructures.” Here, the phrase denotes a way of thinking through how infrastructures, designed to facilitate the movement of goods and people with maximum efficiency, can produce varied emotional affects. In a catalogue essay, Teets writes that this group exhibition is “informed” by Houston. Here, perhaps more than anywhere else in America, infrastructure is the city: the crumbling roads, the non-existent sidewalks, and the looming if stealthy presence of oil refinement and finance.

The show opens with model houses made from old Bible covers by Chiffon Thomas. Attached to the ceiling over the staircase to the exhibition floor, they hover like ghosts. Thomas was inspired by the neighborhoods of his Chicago childhood, but the shaky silhouettes of these model houses could be Houston’s Third Ward, or any poor community where a church promises a better life perspective than the current economy and policy.

In a transgenerational dialogue the curator’s great-grandmother, Josie Ann Teets, an amateur songwriter, meets a young French artist. Josie Ann wrote and published The Oil King Buggie in 1975. The show contains a notation …

January 12, 2024 – Review

An-My Lê’s “Between Two Rivers/Giữa hai giòng sông/Entre deux rivières”

Jacinda S. Tran

In 1968, army photographer Ron Haeberle shot Vietnamese civilians indiscriminately massacred by US ground forces in the hamlet of Mỹ Lai. His photographs circulated widely—including a color photo of corpses strewn across a road featured in LIFE magazine that, in 1970, with support from the Museum of Modern Art, the Art Workers Coalition incorporated into an antiwar poster overlaid, in blood red, with the text “Q. And babies? A. And babies.” When MoMA withdrew its support for the poster, AWC staged a protest to illuminate board members’ tacit support of the war in Vietnam. The museum promptly assimilated AWC’s poster into their own collections, institutionalizing institutional critique.

Half a century later, MoMA exhibits “Between Two Rivers/Giữa hai giòng sông/Entre deux rivières,” a survey of multimedia works by Vietnam-born An-My Lê, whose large-format photographs are known for their staging and depictions of militarized landscapes. Lê focuses on what the visual reveals and obscures; how a range of quotidian landscapes may be conceived as “always already military.” Though Lê left Vietnam as a teenager after the fall of Saigon in 1975, the specter of war and its spectacularization informs her approaches to representation. In “Viêt Nam” (1994–98), Lê returns to her birth …

January 11, 2024 – Review

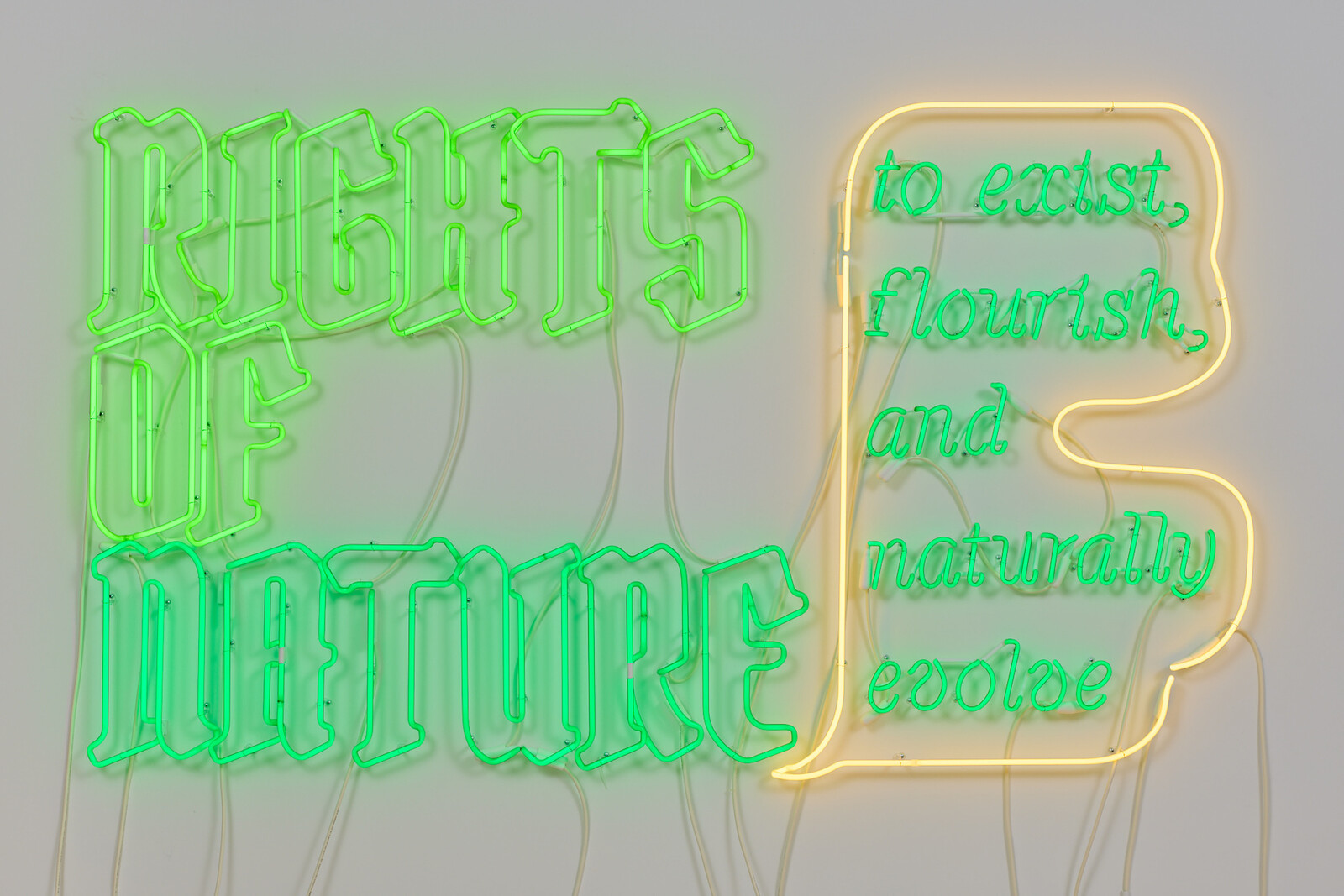

“Green Snake: women-centred ecologies”

Stephanie Bailey

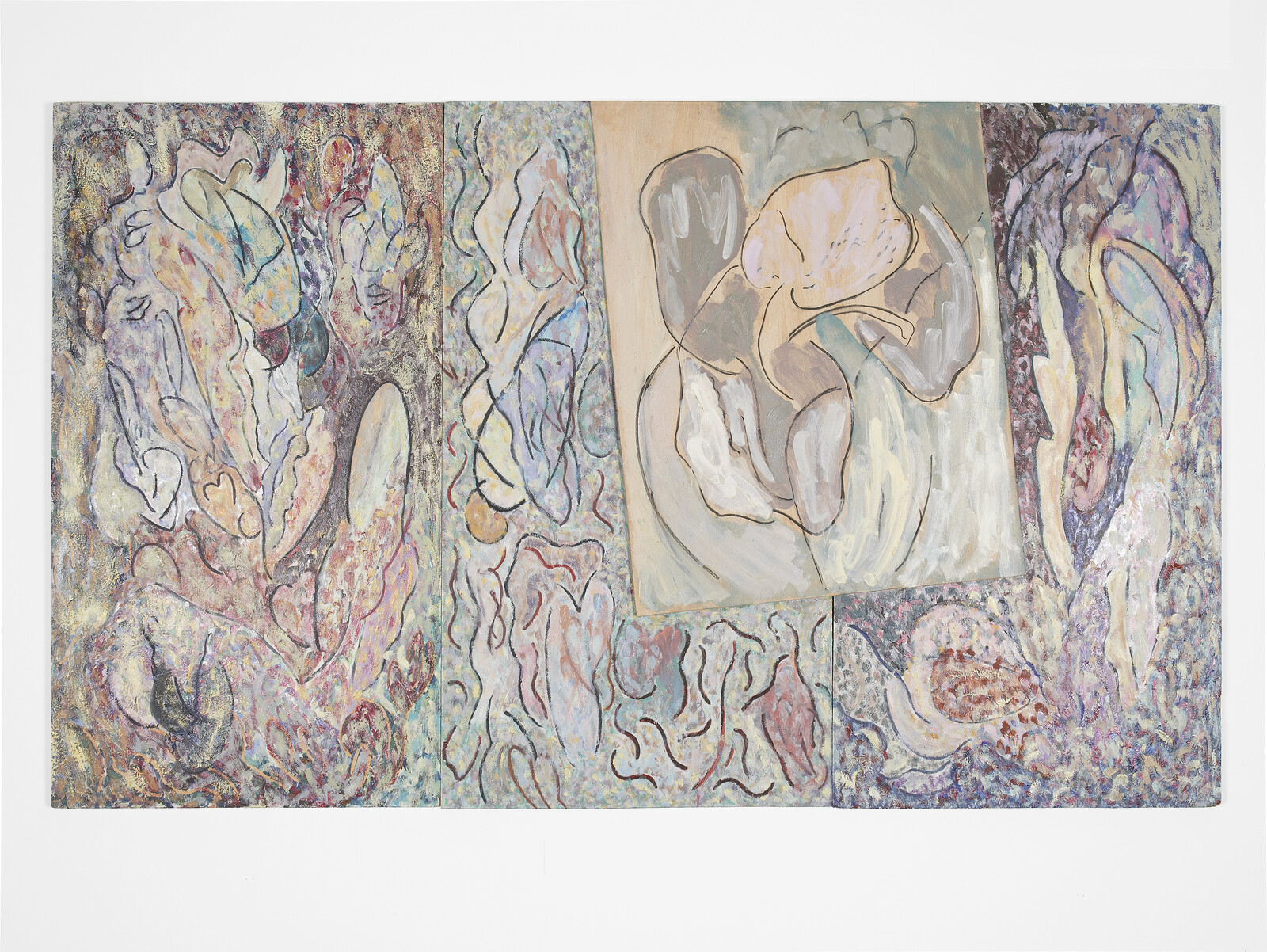

Of all the works in this gathering of cosmological and ecological perspectives, one is anchored directly to the exhibition title. Two moon gates open up the wooden frame enclosing Candice Lin’s Kiss under the tail (all works 2023 unless otherwise stated), where floorspace padded with tatami mats hosts ceramic cats, one with a house for a head, and an indigo-dyed carpet whose patterning replicates a nineteenth-century diagram of a castration by a western missionary who studied eunuchs in China. These gates, and the transformational space they envelope, reference a central location in Tsui Hark’s 1993 movie, Green Snake, a retelling of an ancient Chinese folktale about two female snake demons who endeavored to become human. In the film, the single-minded White Snake pursues the love of a studious male, while the free-wheeling, shapeshifting Green Snake tries to understand the desire that drives her centuries-long companion to her doom. In the end, Green Snake rejects the human world with its apocalyptically heteronormative devotions and questionably immutable morals, realizing she had known love as an affirmation of life all along. So she returns to the water, or rather to nature; an idea that runs through this show.

Projected onto a massive wall …

January 5, 2024 – Review

35th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, “from the void came gifts of the cosmos”

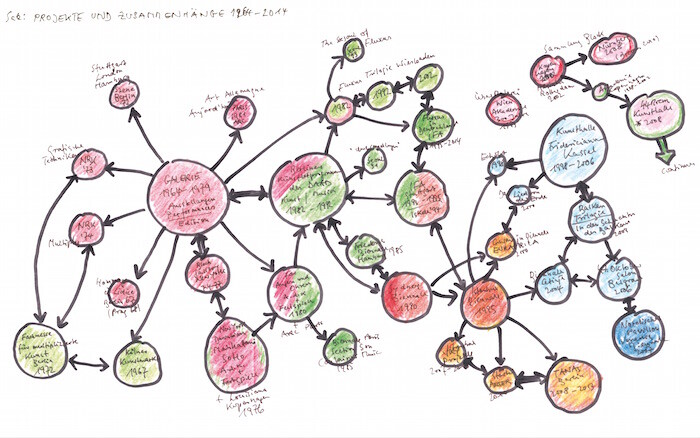

Kate Sutton

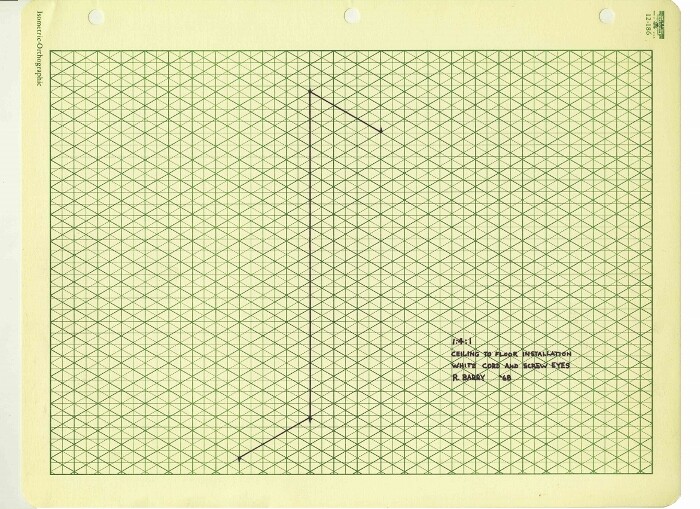

When Ibrahim Mahama agreed to serve as artistic director of the 35th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, he sought inspiration on a domestic scale. The simple conceptual sketch he prepared for this edition—titled “from the void came gifts of the cosmos”—shows a rudimentary bedframe, with a few unidentified objects stashed underneath. This curatorial approach attempts to reclaim an everyday architectural recess from the realm of monsters and recognize it instead as a space of potential. But dark things come from under the bed, the darkest of which may be nothing at all.

Mahama applies the metaphor of the void not only to architectural and ideological infrastructures, but also to emancipatory movements that operate within structures of colonial domination. Chief among these is the Non-Aligned Movement: a political experiment that rejected the either/or imperialism of the Cold War era in favor of a multilateral understanding of the world. Its foundations were laid at the Bandung Conference in 1955, the same year that the Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts launched. Fresh from its split and subsequent rapprochement with the USSR, Yugoslavia offered a meeting ground for representatives from both sides of the Iron Curtain, and the biennial was expressly crafted to strengthen …

December 22, 2023 – Review

Pacita Abad

Tausif Noor

To discuss the life of Pacita Abad is to enumerate the diverse places to which she traveled (some sixty countries across six continents), her expansive artistic output (nearly 5000 large-scale works), and the litany of materials and techniques she applied to the surfaces of her signature stuffed-and-quilted canvases, or trapuntos (sequins, beads, batik prints, and phulkari embroidery, to name just a few). Over a thirty-two-year career—she died of cancer in Singapore in 2004—Abad sidestepped hierarchies between craft and high art and unraveled received notions of the local, national, and global, pursuing instead a vibrant eclecticism that was often at odds with the dominant artistic movements of her time.

The retrospective at SFMOMA—arriving from the Walker Art Center before stops at New York’s MoMA PS1 and the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto—follows Abad’s artistic career as it was shaped by global postwar politics from the aftermath of national decolonization movements in Asia and Africa in the 1960s, through the humanitarianism of the 1970s and ’80s, and the heyday of multiculturalism in the US in the 1990s and early 2000s. In this, Abad’s trapuntos in particular function as what the curator Shabbir Hussain Mustafa has aptly termed an “archive of the …

December 21, 2023 – Review

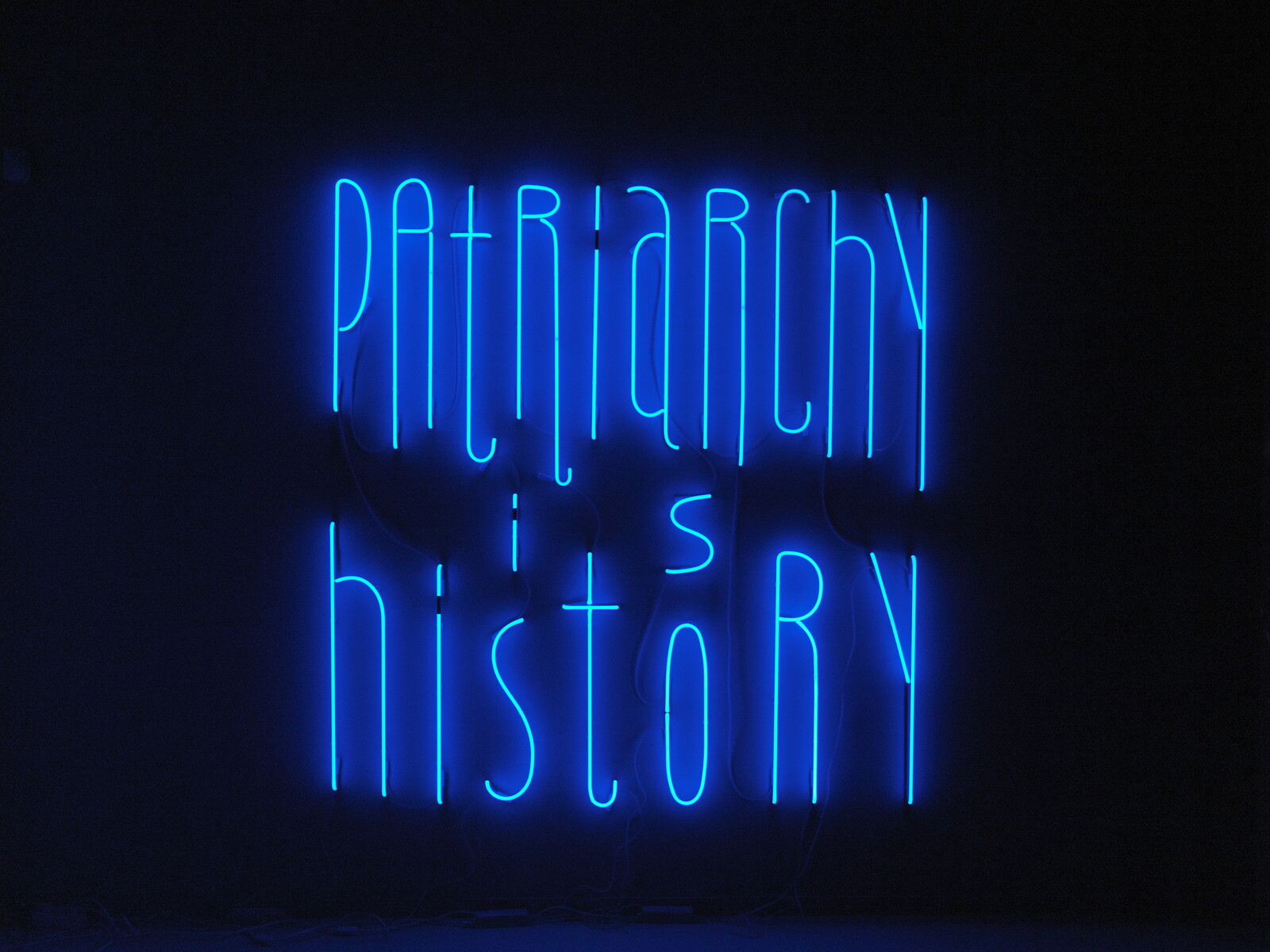

Andrea Bowers’s “Joy is an Act of Resistance”

R.H. Lossin

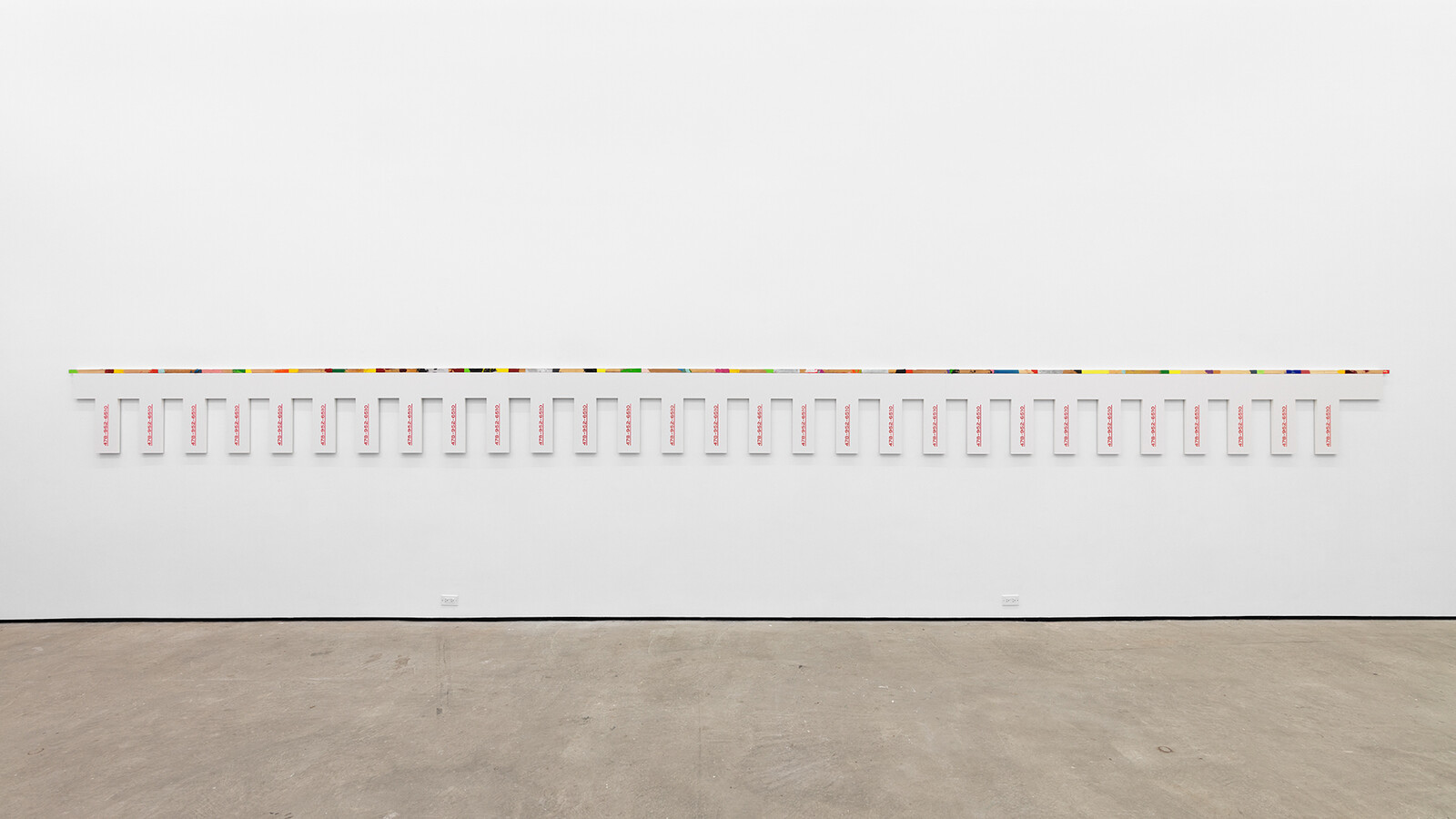

The first work that one encounters on entering Andrew Kreps’s gallery might be mistaken for an extension of the gallery’s commercial operations. Trans Bills (2023) consists of fifty-four black ring binders, arrayed on a shelf to the left of the front desk, labeled with the names of states that have passed legislation restricting the rights of trans citizens. The work’s blandness is perhaps the point. Quietly running in the background of clownish Republican performances of parental rights and viral videos of religious zealots is a legislative machine producing the reams of paper progressively restricting the rights of trans people to work, receive medical care, and live basic social lives. In a mere two years, 1,006 anti-trans bills have been introduced by state legislatures. An additional sixty-three have been introduced at the federal level.

At the back of the first-floor gallery is a 47-minute single-channel video of a trans prom organized by four teenagers as both an adolescent rite of passage and a protest—two things that are, for many trans youth, inseparable. The footage is visible from the gallery’s entrance, and the contrast between the young faces and the scale of adult animosity ranged against them is the show’s most valuable …

December 19, 2023 – Review

Mit Jai Inn

Jenny Wu

In Shirley Jackson’s allegorical short story “The Lottery” (1948), villagers gather for a game of chance in which they draw slips of paper, all blank but one, from an old black box. Children, adults, and elders alike, accustomed to the tradition, participate with a mixture of anticipation and boredom. The ending reveals that the prize, known to them all along, is the stoning of an unlucky villager. Mit Jai Inn’s first US solo exhibition also features a large quantity of “stones” and a lottery that, in subtler ways, uncovers a set of human behaviors integral to the functioning of society and politics. Here, the Chiang Mai-based artist, whose work is often framed as a form of social practice infused with Buddhist teachings, sets up a participatory piece titled after a recent sculpture series, Marking Stones (2022). Visitors are invited to submit pledges for “positive action” for a chance to win one of these sculptures.

The title of the series is a tenuous reference to the bai sema stones used by Buddhist communities in Southeast Asia to mark their territory: the sculptures are, in fact, fully functional baskets, lamps, and stools. Around two dozen of these candy-colored wares occupy a room …

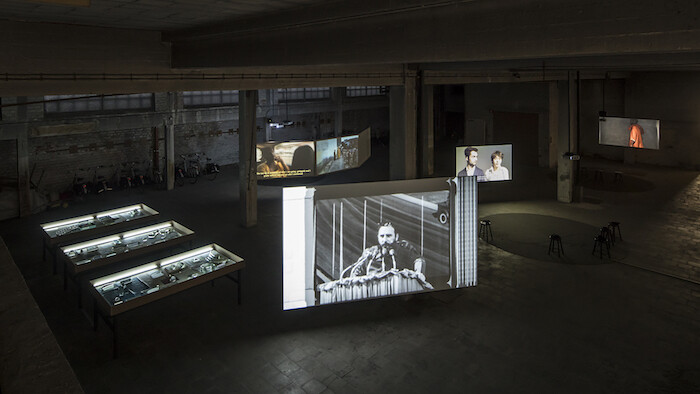

December 18, 2023 – Review

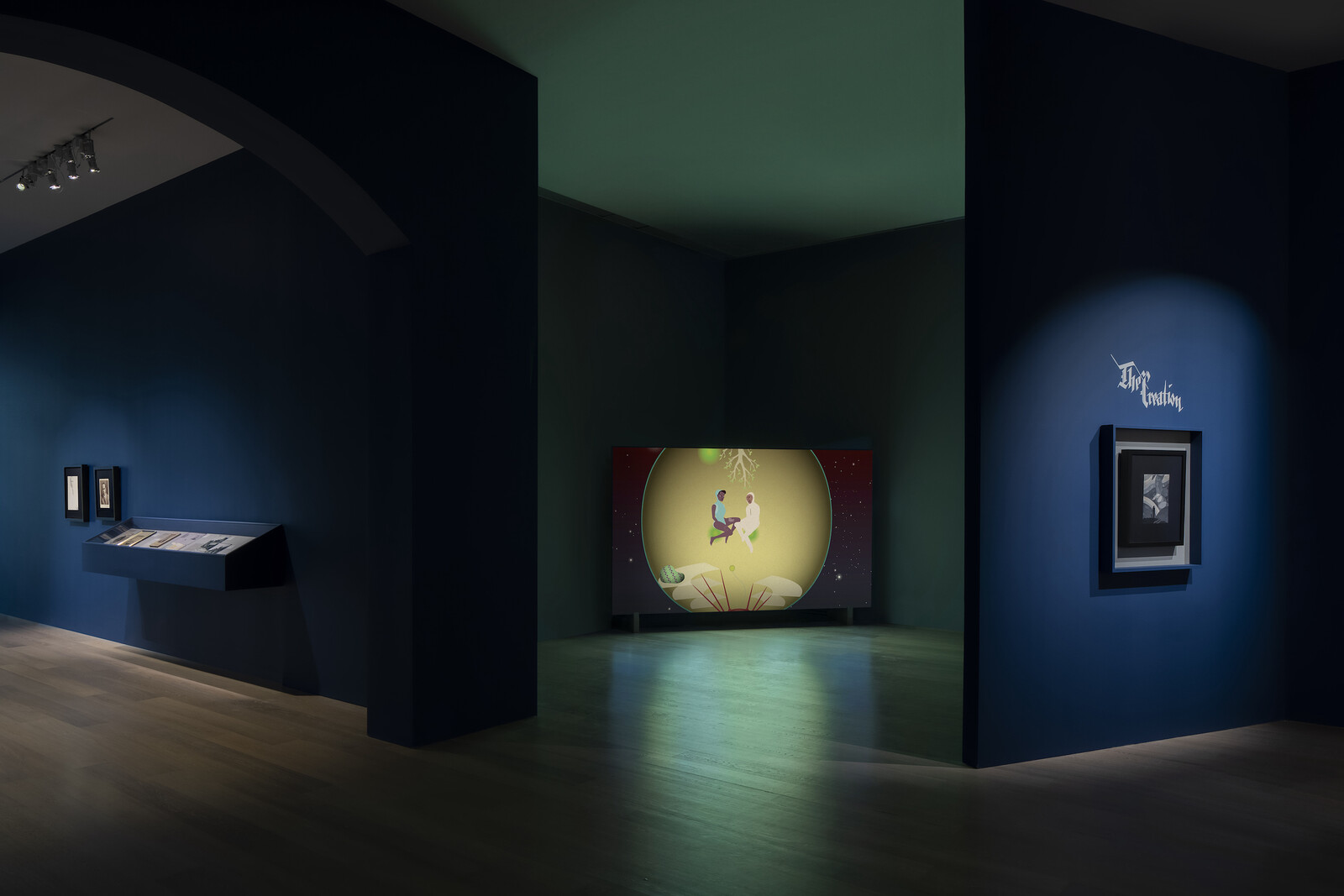

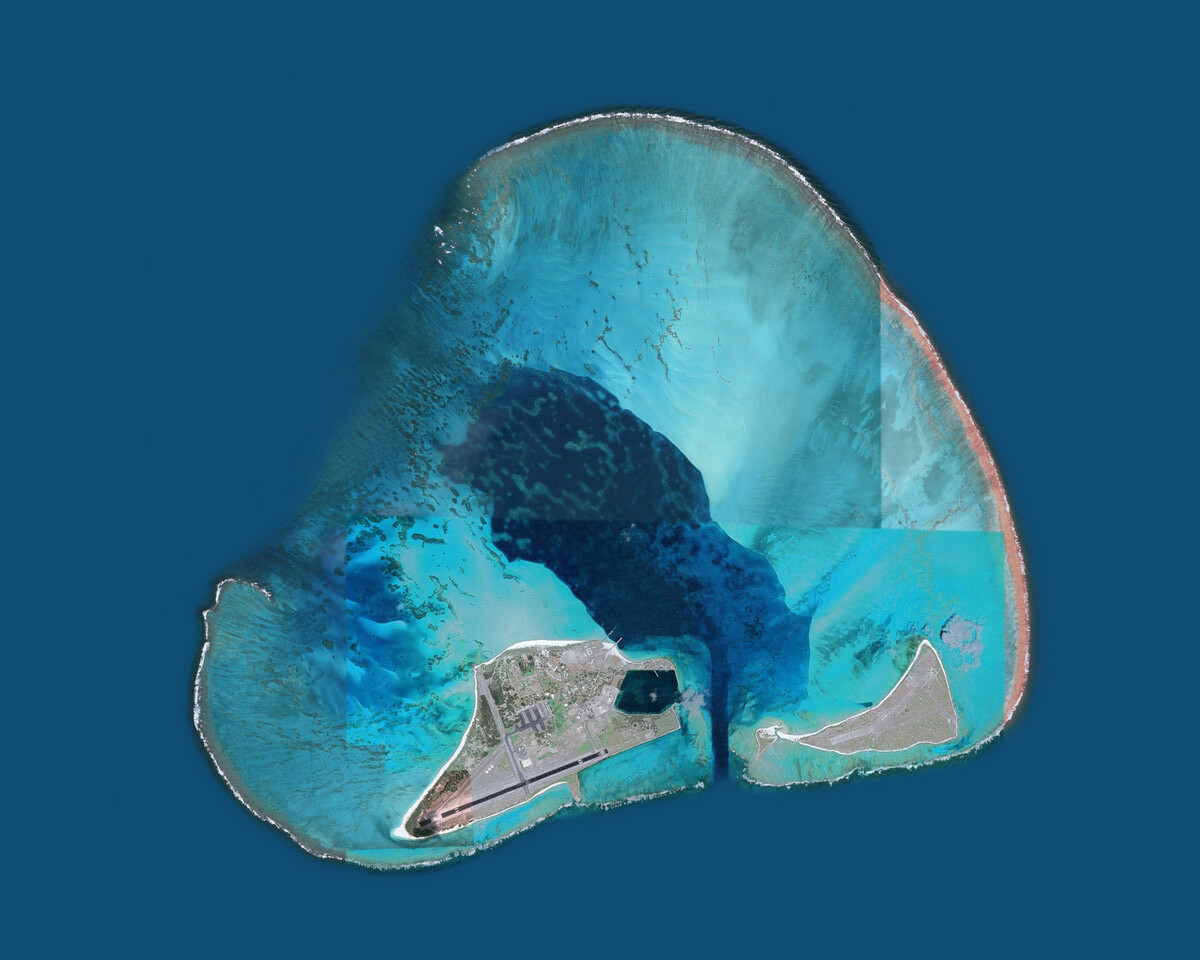

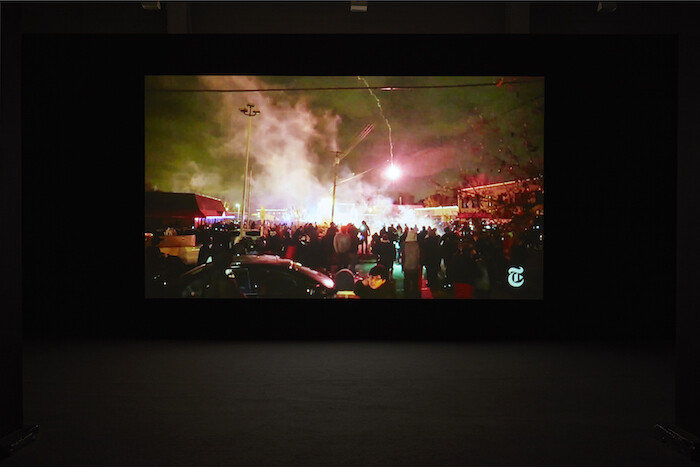

Paul Pfeiffer’s “Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom”

Juliana Halpert

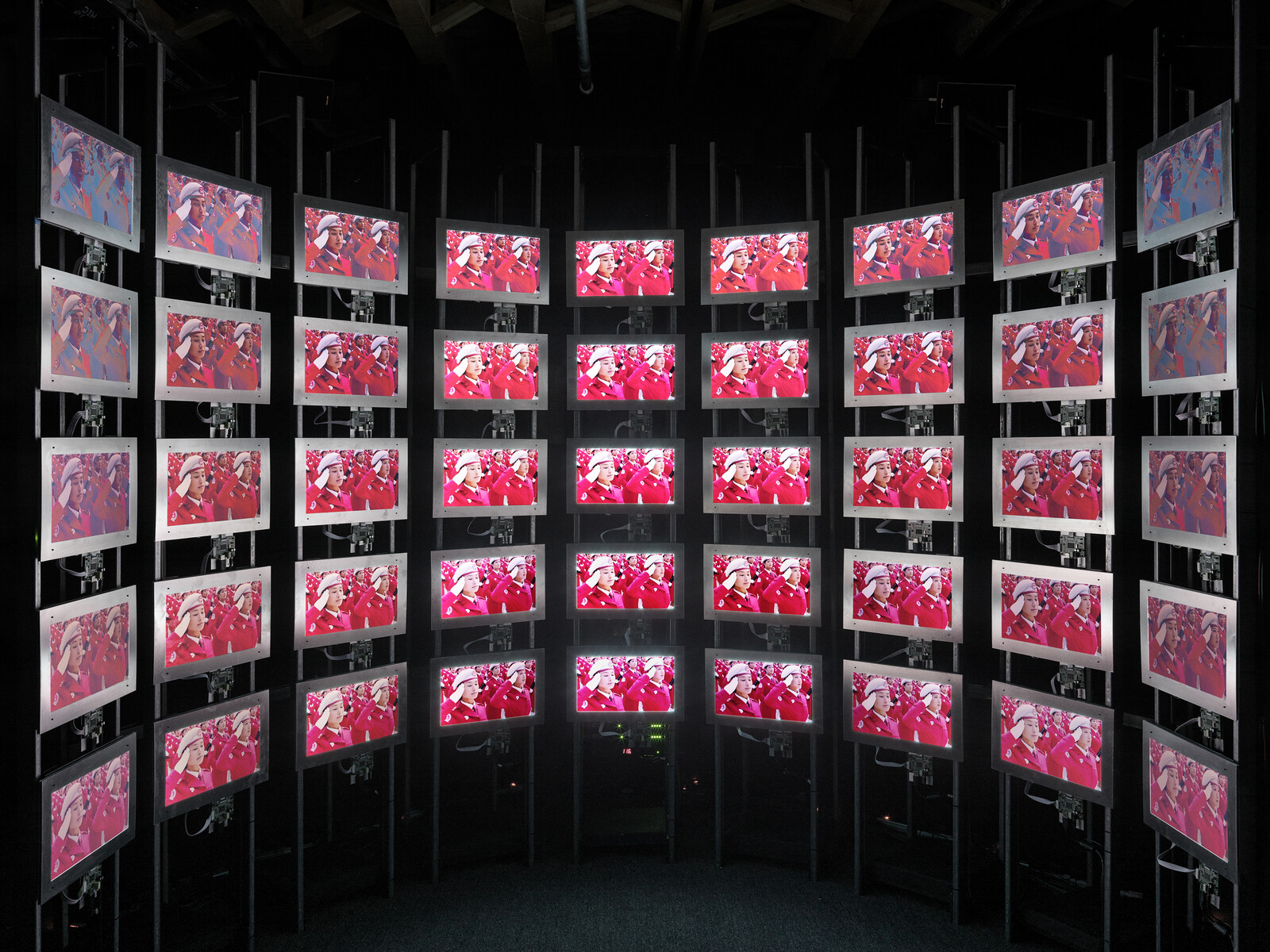

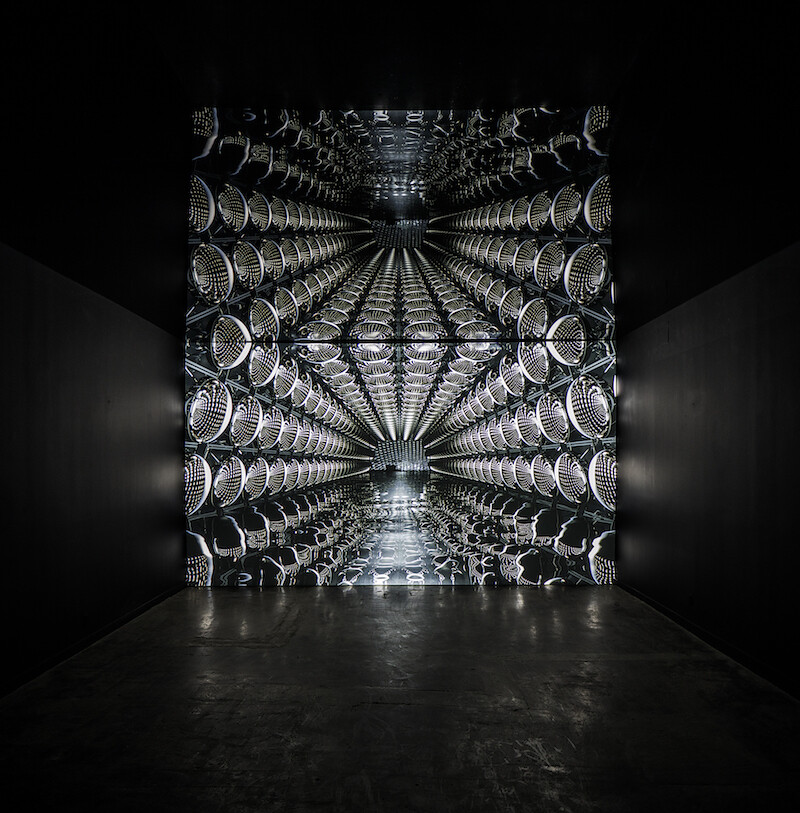

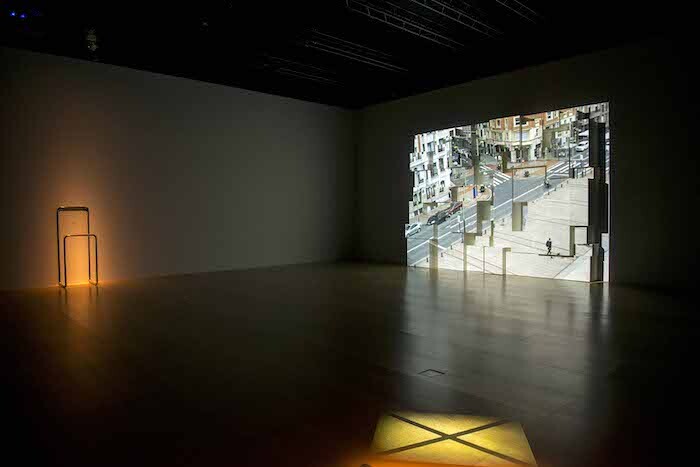

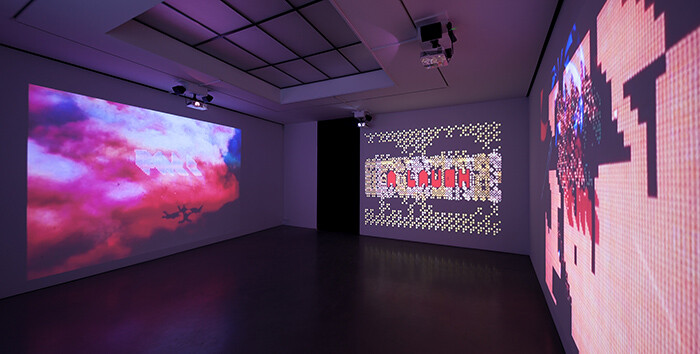

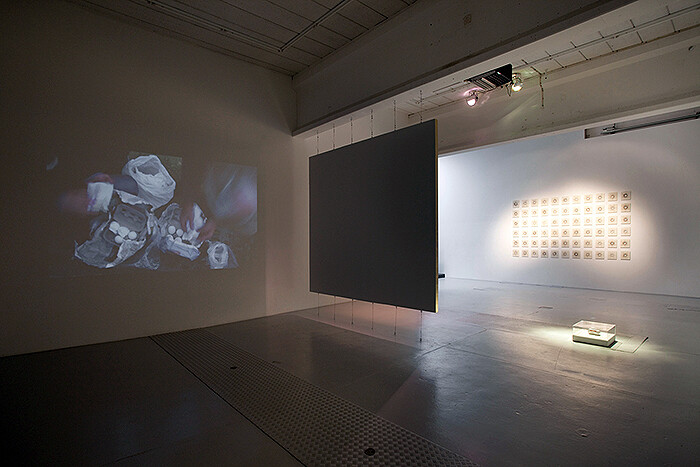

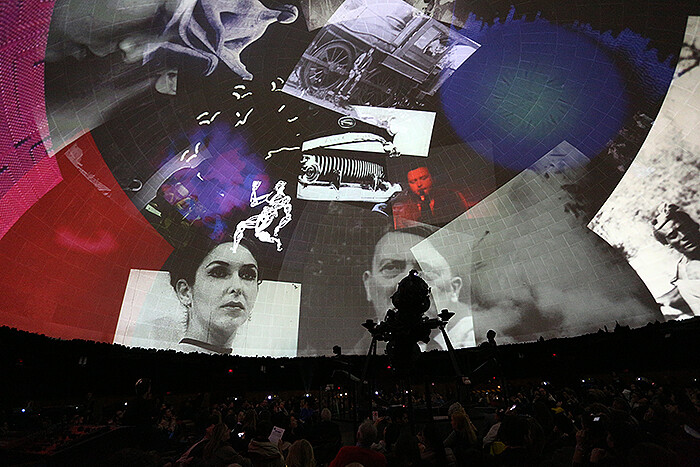

Trying to find a critical entry point into—or exit from—Paul Pfeiffer’s retrospective is not unlike the challenge of navigating its labyrinthine layout of walls, ramps, and rooms within rooms. An architecture designed by the artist with Hollywood sound stages in mind slowly unveils a spectacle of spectacles, showcasing over thirty works spanning the past twenty-five years and dizzying ranges of scale, duration, material, and method. Pfeiffer is best known for his bite-sized video works, which sit here alongside extra-large installations, miniature dioramas, full-scale sculptures, room-wide projections, and expansive photo series. Video durations range from four seconds to ninety days. Most of his moving-image works have no sound, but the space hums with the distant, ambient clamor of a crowd. Michael Jackson’s voice has been replaced by that of a Filipino choir. The Stanley Cup levitates in mid-air. Marilyn Monroe and Muhammad Ali have been scrubbed out of their respective beaches and boxing ring. Raucous activity and haunting absence somehow go hand-in-hand.

If there’s a true North to Pfeiffer’s practice, it might be mass media’s protean relationship to consumer technology, how the latter shapes the former and vice versa. It’s a marvel to witness the artist’s use and abuse of both, …

December 15, 2023 – Review

Delcy Morelos’s “El abrazo”

Michael Kurtz

Here lie the ruins of the American avant-garde. Wood salvaged from an installation by Dan Graham, offcuts from a felt piece by Robert Morris, and scraps of flooring from a Dorothea Rockburne display. Mounds of soil recall Robert Smithson’s geological samples and rows of pipe echo Walter de Maria’s Broken Kilometer (1979) of brass rods lined up on the floor. These fragments now sit in darkness, illuminated only by four shaded skylights. They are arranged across the space along with sheets of corrugated metal, parallel stacks of wooden planks, and hundreds of small pieces of Colombian pottery. Everything is dark brown and sitting on a crust of mud which rises up the walls to a high-water mark, I later read, left after the gallery flooded during Hurricane Sandy.

Despite their simple forms and materials, the objects become mirage-like in this dimly lit monochrome expanse. Walking down the pier of clean floor that stretches into the room, I try to perceive the scale and texture of the things around me, but they evade my grasp. The light fades and they retreat further. Cielo terrenal [Earthly heaven] (2023), the first of two installations by Colombian artist Delcy Morelos at Dia Chelsea, is …

December 13, 2023 – Review

Henry Taylor’s “From Sugar to Shit”

Novuyo Moyo

The people in Henry Taylor’s paintings are usually surrounded by slabs of color, a graphic sensibility he shares with his high school peers and alternative comic book artists Los Bros Hernandez, whom he credits with setting the bar for his work. “I always thought, ‘Damn, they draw so much better than I.’ So I started just practicing my draftsmanship because of them. They intimidated me.” Taylor worked for ten years as a technician at Camarillo State Mental Hospital while studying at CalArts, providing assistance to some of the area’s most vulnerable people and at times featuring them in his drawings and paintings, developing the empathetic lens through which he would continue to frame his subjects.

Set in Hauser and Wirth’s Parisian multi-story outpost, and consisting of works made between 2015 and 2023 (the most recent made during a stay in Paris over the summer), “From Sugar to Shit” connects past and present, interior and exterior, public and private. Taylor’s subjects range from famous faces to personal acquaintances, but his frank, inquisitive approach sees both groups as equally worthy of commemoration. It’s not always clear whether he works from memory, archival materials, a live sitting, or a combination of these, but …

December 12, 2023 – Review

Sanya Kantarovsky’s “The Prison” with Yasuo Kuroda’s “The Last Butoh”

Jennifer Piejko

Tatsumi Hijikata spoke with his entire body. At Nonaka-Hill, Yasuo Kuroda’s photographs of his performances of Butoh—the form of dance theatre he founded in postwar Tokyo—are displayed alongside new paintings by Sanya Kantarovsky, advancing the latter’s interest in Japanese folklore and traditions. The subjects on the canvases resemble the dancers in the photographs, as if painted from hazy memories or fever dreams. Though not directly depicting the same figures or moments, the two approaches to image-making are complementary: both capture the depths of estrangement, enveloped dislocations, and solitary sorcery of performance.

Each lone figure in Kantarovsky’s paintings expresses a different facet of pain. No Longer a Dog and I am a Body Shop (all Kantarovsky’s works are dated 2023) show figures who mirror traditional Butoh performers, turned away and covered in the Japanese white paint of mourning over their faces and limbs, ribs visible through their nearly translucent skin. In Bleeding Nature, the dancer suffers from the kind of wound that a Butoh dancer might feel in phantom form: an open gash over a bloody heart. Their bottom half disintegrates into ribbons, dangling from their fingertips and torso into a swirl of entrails that fertilizes a surrounding field of flowers …

December 8, 2023 – Review

2nd Sharjah Architecture Triennial, “The Beauty of Impermanence: An Architecture of Adaptability”

Nick Axel

The second Sharjah Architecture Triennial—featuring twenty-nine architects, artists, and designers across two main venues (the Al Qasimiyah School and Old Al Jubail Vegetable Market) and a handful of off-site locations—reckons with the cultural and ecological legacies of colonialism and modernity. The work shown does not, in the words of its curator, the Nigerian architect Tosin Oshinowo, simply acknowledge a wrong or apologize for the past. Instead, the contributions demonstrate modes of practice that build new worlds from the ruins of the present. Ideas of “impermanence” and “adaptability” here describe creative responses to conditions of scarcity that draw on ancestral ways of knowing and resourceful forms of making, and “beauty” as a celebration of survivance.

This triennial is in many ways a spiritual successor to Lesley Lokko’s international exhibition at the most recent Venice Architecture Biennale, “The Laboratory of the Future.” Beyond the handful of contributors to appear in both, in these exhibitions architecture is often a starting point, theme, and subject more than an end with pre-defined means. This approach liberates the exhibition from the representational conventions of architectural media (drawings, diagrams, models, maps, and photographs) in favor of immersive installations, sculptural works, films, and more that overcome the alienating …

December 7, 2023 – Review

Shilpa Gupta

Paul Stephens

Recent New York Times headlines point to American perceptions of India’s increasingly prominent role in global affairs. “Can India Challenge China for Leadership of the ‘Global South’?” “Will This Be the ‘Indian Century’?” “The Illusion of a US-India Partnership.” “US Seeks Closer Ties With India as Tension With China and Russia Builds.” “US Says Indian Official Directed Assassination Plot in New York.” “An Indian Artist Questions Borders and the Limits on Free Speech.”

The last headline refers to Mumbai-based Shilpa Gupta, whose work obliquely explores the emergent global polycrisis (a term popularized by Adam Tooze) in which India plays a central part. Although Gupta’s art is deeply engaged with contemporary political events, it is not headline-driven. It resists didacticism, in part, through being polyvocal, as exemplified in her standout installation Listening Air (2019–23). Defying simple description and rewarding patient immersion, Listening Air consists of multiple microphones-turned-speakers that play songs of labor and resistance from around the world. As the songs fade in and out, listener-viewers in the dimly lit room slowly begin to perceive themselves as members of a temporary community. The effect is ethereal and meditative.

Gupta’s two concurrent New York exhibitions, at Amant and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, accord …

November 29, 2023 – Review

Lisa Brice’s “LIVES and WORKS”

Louise Darblay

“Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at,” goes John Berger in his classic BBC show Ways of Seeing (1972), his big blue eyes staring intently at the viewer while he demonstrates the impact of centuries of male gaze—from canonical paintings to contemporary advertising—on the way women perceive themselves. “The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed is female. Thus she turns herself into an object of vision: a sight.” In Lisa Brice’s paintings, which wander the corridors of western art history, women look at themselves, but no longer through this mediated perspective: the muses, models, and mistresses come to life, turning from passive objects into active subjects, becoming the authors and surveyors of their own image.

This new series by the South African artist, presented on the ground floor of Ropac’s Marais space, bristles with punkish energy. Two large, cinematic canvases mirror each other on opposite walls, their horizontal compositions drawn from Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882). In the most obvious riff on his work, Untitled (after Manet & Degas) (all works mentioned 2023), the Folies-Bergère has turned into a women-only cabaret, populated by sexy and brazen dancers (including Manet’s sad-looking barmaid, …

November 28, 2023 – Review

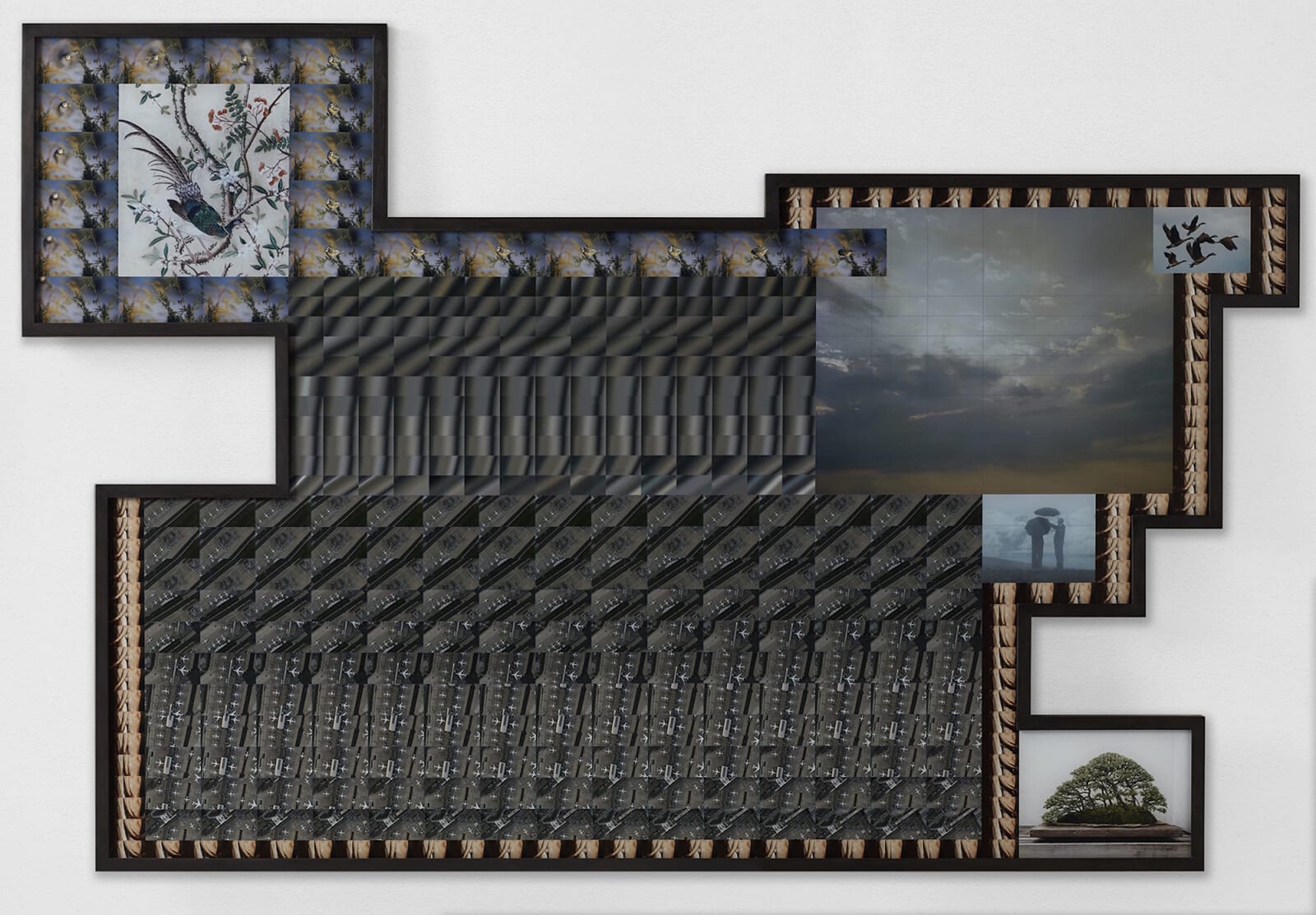

12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, “THIS TOO, IS A MAP”

Jason Waite

“THIS TOO, IS A MAP” questions the conventional relationship of map to territory, looking “to model multi-spatial and multi-subjective histories and knowledge.” Directed by Rachael Rakes with associate curator Sofia Dourron, the show features works by sixty-five artists chosen not as representatives of particular nations but for their embrace of transnational approaches. The diasporic bent of this list reflects an expansion of (and alternative approach to) cartography to articulate myriad overlapping personal roots and routes.

One example is Tibetan-American artist Tenzin Phuntsog, whose video Pure Land (2022) attempts to trace landscapes across the American West that look similar to images of a homeland he’s never visited. In the film, he messages these images to his mother to comment on or verify their similitude. In the construction of these unknown nostalgic landscapes, the images Phuntsog takes are uncannily similar to their Tibetan counterparts. The comparison highlights the possibility that any space can be made into a home. At the same time, it floats subtle questions of what defines any given place.

What lies underneath a landscape was the focus of one of the more unique venues of the biennale: an emergency bunker built for the former military dictator Park Chung …

November 23, 2023 – Review

“Indian Theater: Native Performance, Art, and Self-Determination since 1969”

Alan Gilbert

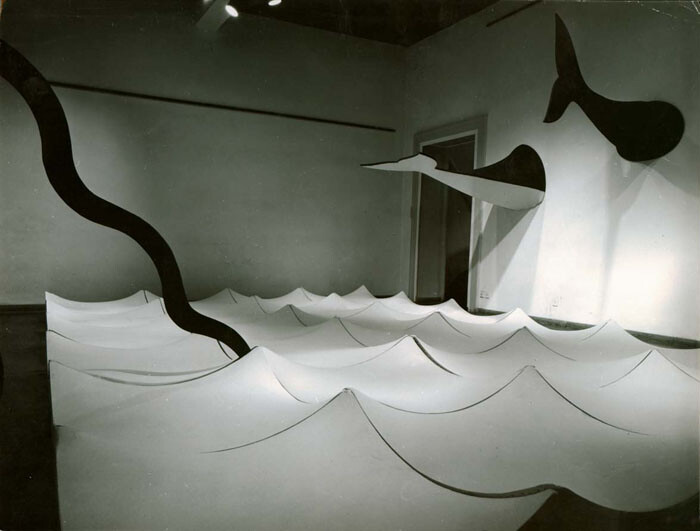

In November 1969, a group of Native activists sailed across San Francisco Bay and occupied Alcatraz Island, home to the infamous prison that had closed in 1963. The occupation lasted until the summer of 1971, when federal authorities besieged the island by cutting off the electricity and water supply before government agents and local police removed the dozen or so remaining inhabitants. The year 1969 also saw the publication of the pamphlet “Indian Theatre: An Artistic Experiment in Process,” written collaboratively by Lloyd Kiva New (Cherokee), Rolland Meinholtz (Cherokee), and students at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It called for the combination of contemporary theater practices with performative and ritual aspects of Native societies in an effort to bring marginalized Native stories and cultural forms to a reimagined stage.

The large survey exhibition “Indian Theater: Native Performance, Art, and Self-Determination since 1969,” curated by Candice Hopkins (Carcross / Tagish First Nation) at the Hessel Museum of Art, opens with archival documents in vitrines highlighting these two historical moments. Pages of “Indian Theatre: An Artistic Experiment in Process” are given pride of place at the entrance next to undated, grainy black-and-white videos of Native performances …

November 22, 2023 – Review

Neïla Czermak Ichti’s “J’adore vous faire rire”

Natasha Marie Llorens

A diminutive and oddly classical homage to the eponymous character in Ridley Scott’s 1979 classic horror film Alien, entitled Bolaji resting between two takes (2023), is tucked into one corner of the front room of Anne Barrault’s gallery in Paris. The painting is small, the facture thick, with a palette in shades of white. The composition’s contrast is rendered in a warm maroon tone that reminds me of blood coagulating at the edges of a flesh wound. Despite this latent suggestion of violence, Franco-Tunisian artist Neïla Czermak Ichti’s portrait of the infamous being eschews the sexualized viciousness of its on-screen presence. Seated on a cheap plywood block, visibly marked by use, with its massive head resting on long, thin forearms, the alien just looks tired, like a construction worker on a fifteen-minute break.

Czermak Ichti became obsessed with Bolaji Badejo, the twenty-five-year-old Nigerian art student inside Ridley’s oppressive latex costume. She based the painting on one of only a handful of production photographs of the costumed actor between shots. Badejo was born in Lagos in 1953, immigrated to Ethiopia with his family in the aftermath of the Nigerian civil war (1967–70) and then to the UK. The one-time movie star …

November 21, 2023 – Review

Jessica Segall’s “Human Energy”

Cassie Packard

Jessica Segall’s transgressive exploration of desire and petroleum unfolds to the beat of a mechanical soundtrack. The work of Berghain resident DJ Steffi, building on Segall’s own recordings of active oil fields, the piston-like pulsations fuse petro-extraction and the nightclub. Desire—for dominion, capital, commodities, relations—has always powered industry; here, industry clearly powers desire, too. Petroleum’s libidinal imaginary encompasses everything from imagery of women virtually fornicating with automobiles to the more abstract seductions of movement, convenience, ease, and accumulation. In Human Energy (2023), a dispersed four-channel video installation with sculptural elements (titled after Chevron’s slogan), Segall renders these fetishizations with erotic effect.

On one channel, the scantily clad, gloved artist climbs and mounts a pumpjack. She rides it as if it were a mechanical bull, moving her hands back and forth to steady herself while the machine repeatedly plunges into the earth. The video was shot in Kern County, California, which is responsible for the vast majority of the state’s oil and fracked gas production and boasts some of the worst air pollution in the country, a burden disproportionately borne by the region’s most vulnerable communities. Panoramic open sky, mountain range, sunset: our petro-cowgirl deploys the tropes that have characterized fantasies …

November 17, 2023 – Review

Ali Cherri’s “Dreamless Night”

Cathryn Drake

Ali Cherri’s The Watchman [Nöbetçi] (all works 2023) follows a young Turkish Cypriot officer stationed at a watchtower in Akincilar, a district encircled by the meandering border drawn across Cyprus after the Turkish invasion of 1974. Adjacent to the closely patrolled United Nations Buffer Zone, it is a desolate, transitory place where nothing really happens. On the horizon are the crumbling ruins of a village abandoned by Greek Cypriots. When the loudspeaker announces the end of his shift, Sergeant Bulut doesn’t move, his bloodshot eyes staring into the camera as if hypnotized by the drone of cicadas. The soldier’s routine is occasionally interrupted by a robin crashing into the dusty glass, leaving a splotch of blood and feathers; Bulut dutifully retrieves each body and records the collateral casualty with another tick on the wall.

This film is not about a particular place: Cyprus, a geopolitically strategic territory that has passed from empire to empire since antiquity, here stands for the postcolonial state of the world and, with much of its population exiled within their own country, the existential condition of so many in contemporary society. On the southern coast lies the British Overseas Territory, a legacy of colonial rule. Turkish …

November 16, 2023 – Review

Lisa Tan’s “Dodge and/or Burn”

James Taylor-Foster

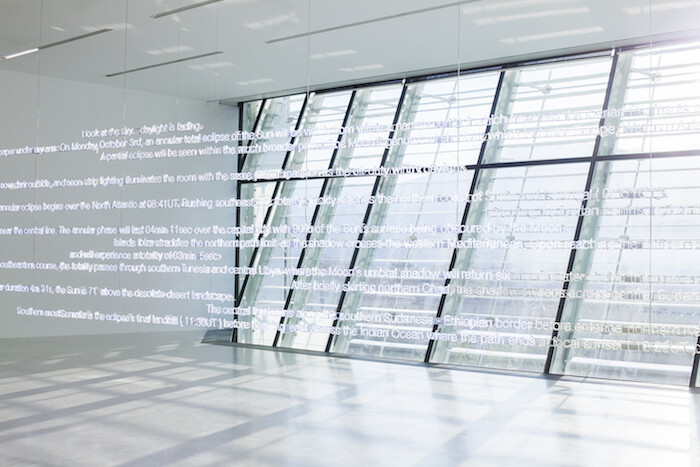

Slicing through subterranean exhibition halls that were previously university laboratories for research in accelerator physics, Lisa Tan’s first institutional show in Sweden tenders its own spatial logic through the metaphor of neurological disorders. Visitors are received by an ink-drawn diagram based on Oliver Sacks’s 1970 sketch of “migraine and neighboring disorders” (from a book said to have been written over just nine days, aided by an undisclosed psychoactive substance). Here, the diagram is superimposed on a detailed schematic of the galleries: I enter the exhibition through “protracted vegetative reactions.”

Tan treats Sacks’s diagram as a tool, scaling it up to a dizzying and dysfunctional domestic space by way of partial walls which operate as spatial dividers, passages, atmospheric zones, and display environments. Rhythmic and austere, this site-specific installation of previous works lays bare the delicate negotiation between control and collapse on which our lives depend. As an organizing principle, Promise or Threat (2023) reveals how rooms are diagrams that shape the ways in which we interface with the world. We move like ghosts, seen and unseen, between spaces that give form to the inner self: the anxiety of a family dinner, the pressure of a deadline, the monotony of a …

November 14, 2023 – Review

22nd Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil, “Memory is an Editing Station”

Oliver Basciano

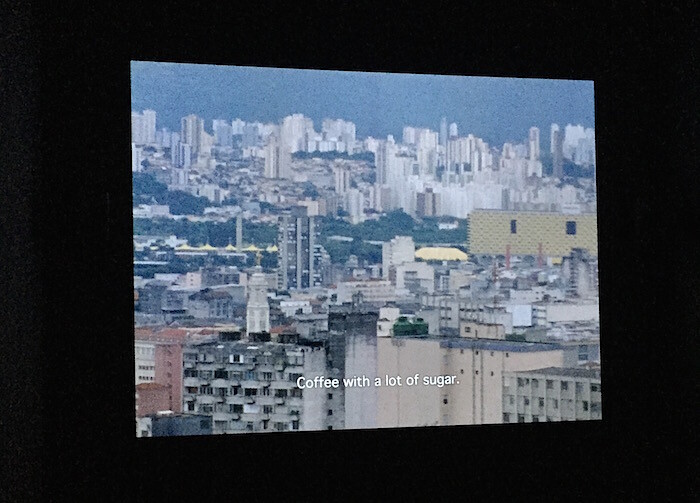

If the Global South is itself an imagined community then, this edition of Videobrasil suggests, therein might lie its emancipatory power. Exhibitions focused on the Global South are in welcome vogue, from the current Bienal de São Paulo to next year’s Venice Biennale, but Videobrasil has been ploughing the furrow for thirty of its forty years now. While curators Raphael Fonseca and Renée Akitelek Mboya took a line by poet Waly Salomão as their guide to select sixty artists from thirty-eight countries out of 2,300 open submissions, this edition is most effective as a snapshot of the conscious and unconscious preoccupations of a constructed region. One that, for the curators, stretches from South and Central America, to Africa, Asia, and former Soviet states (as well as Indigenous artists from any continent). This region, the curators suggest, is “a plural and fertile accumulation of visions.”

What binds this imagined community together? On a series of plinths, Ali Cherri has placed what seem like stone monuments of antiquity—which they are, in part. The scrunched, snarling face and neat mane of Lion (2022) is a historic architectural fragment that the Lebanese artist found in a Beirut antique shop. The bulky clay body, however, …

November 9, 2023 – Review

Meredith Monk’s “Calling”

Patrick Langley

Oude Kerk is a fittingly resonant venue for Meredith Monk’s first—long overdue—retrospective in Europe. This massive thirteenth-century church houses highlights from a polymathic six-decade career that respond to (and echo in) its cavernous nave, with its vaulted wooden ceilings and looming pulpits, its high choir and chapels. To visitors (such as myself) who have only previously encountered Monk’s work via recordings, “Calling,” curated by Beatrix Ruf of the Hartwig Art Foundation, is a revelation. It brings together hypnotic video installations, sculptures, and archival material, yet the result is cohesive, not cacophonous. Each work has space to breathe. Together, they form a harmonious whole.

Several pieces have been revised or reimagined for this show. Amsterdam Archaeology (2023), an iteration of a work first shown in 1998 and the first viewers see upon entering, is one example: a red ziggurat for the display of objects donated by city residents and dipped in beeswax (or “Beuys wax,” as it risks being known in art contexts). These yellowish, translucent cauls point to the union, evident across this exhibition, of industrious and protective instincts. Monk has for decades sought the holistic union of art and healing.

Installations housed in freestanding (and judiciously soundproofed) rooms extend …

November 7, 2023 – Review

Lutz Bacher’s “AYE!”

Michael Kurtz

The first room of “AYE!” is carpeted with fine sand. Audio from Philip Kaufman’s 1988 film adaptation of The Unbearable Lightness of Being fills the air. “Tomas,” a woman asks between kisses, “what are you thinking?” To which Tomas replies: “I’m thinking how happy I am.” The clip loops—the lovers locked in this tender moment, accompanied by piano music and the thrum of rain and windscreen wipers—and with every repeat becomes more cloying and meaningless. Four television screens in a row to one side emit a white glow which fades each time the loop ends, an electronic sunset on the beach. There is a formal resonance between the artificially uniform texture of the sand, the blank monochrome screens, and the eternally recurring sweet nothings. In these elements—nature, entertainment, love—we seek comfort, but here find them in a state of entropy: metronomic, sterile, vacuous.

A child in red dungarees arrives at the door and points at me. “There’s a big man in the sandpit,” she announces to her father, getting his reassurance before dancing freely across the room. She writes her name in the sand, and in doing so shares something that the pseudonymous Lutz Bacher, who died in 2019, never …

November 3, 2023 – Review

New Red Order’s “The World’s UnFair”

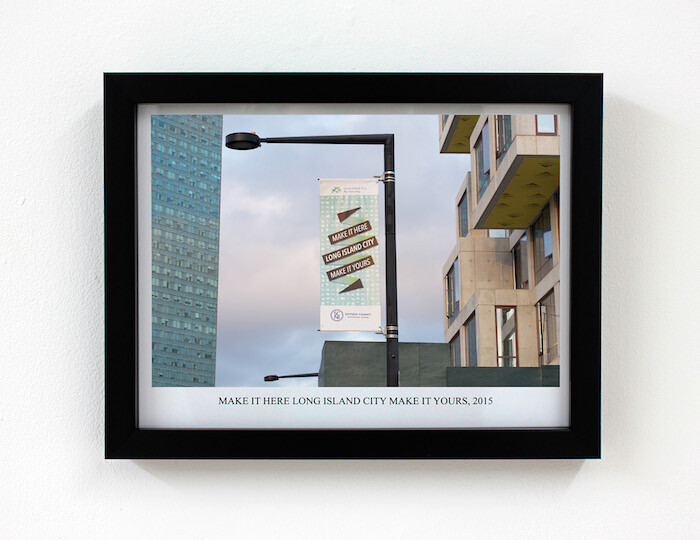

Stephanie Bailey

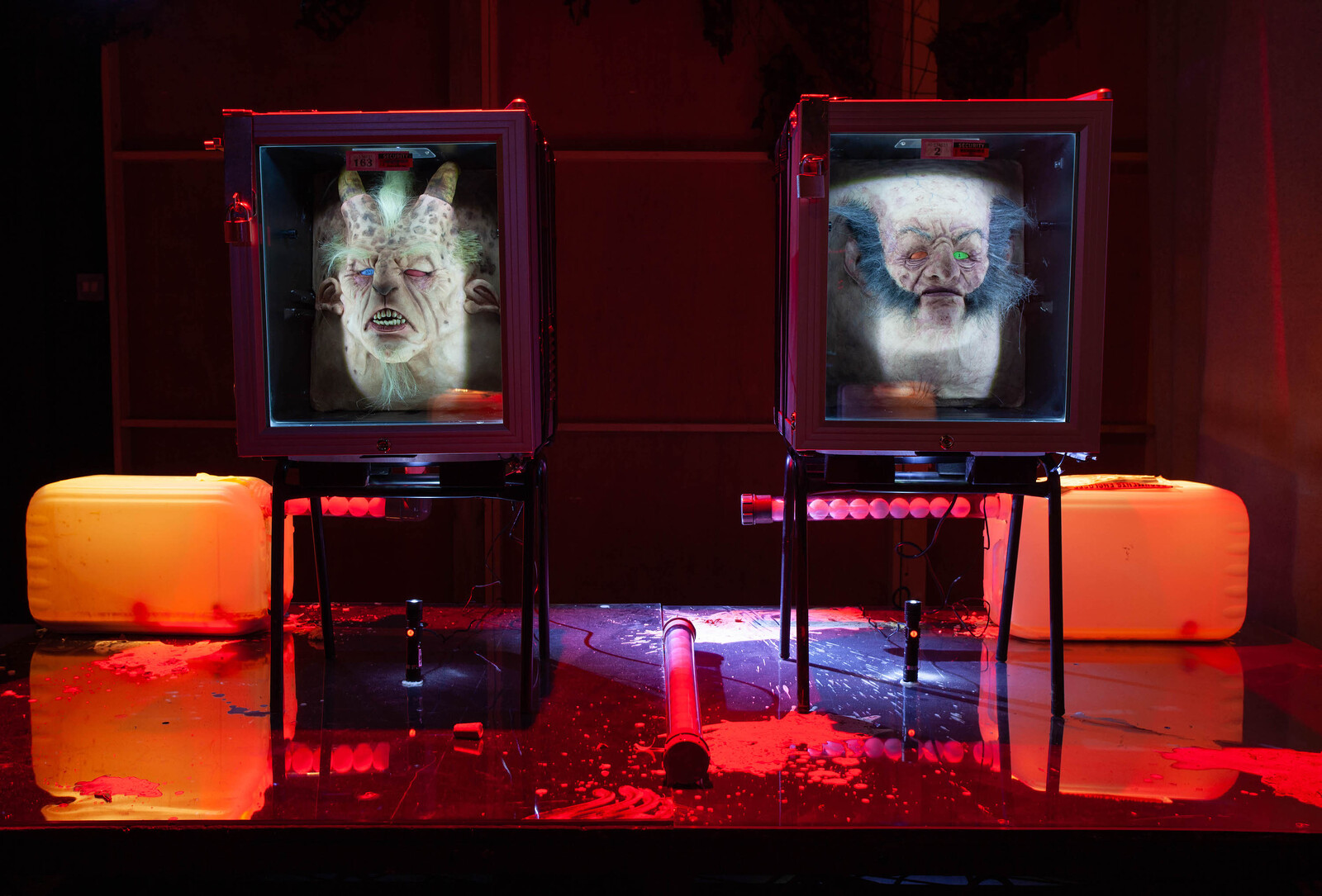

Occupying a pocket of undeveloped land in Long Island City, “The World’s UnFair” is a principled riot. Created by New Red Order (NRO), a “public secret society” facilitated by artists Jackson Polys, Zack Khalil, and Adam Khalil, this carnivalesque fairground, supported by Creative Time, is presided over by Ash and Bruno, a sixteen-foot animatronic tree with LED screens nestled in cellular tower branches and a furry five-foot tall beaver, respectively. The pair talk about the legacies of settler colonialism on the land where they stand, Lenapehoking—a forest, they say, the last time they met. America’s original multi-millionaire John Astor is mentioned: he made his fortune in the fur trade that all but decimated beaver populations, before acquiring land in Manahatta and making “a killing off renting to incoming settlers.”

The politics of land is at the heart of this roadshow. Staked into the earth is New Red Right to Return (2023), a wooden post with directional markers naming Lenape diasporic nations displaced by settlers due to the fundamental difference between the colonial European treatment of land as a commodity and the Indigenous American understanding of it as a communal resource. That discrepancy complicates the narrative that the Lenape sold Manahatta …

November 2, 2023 – Review

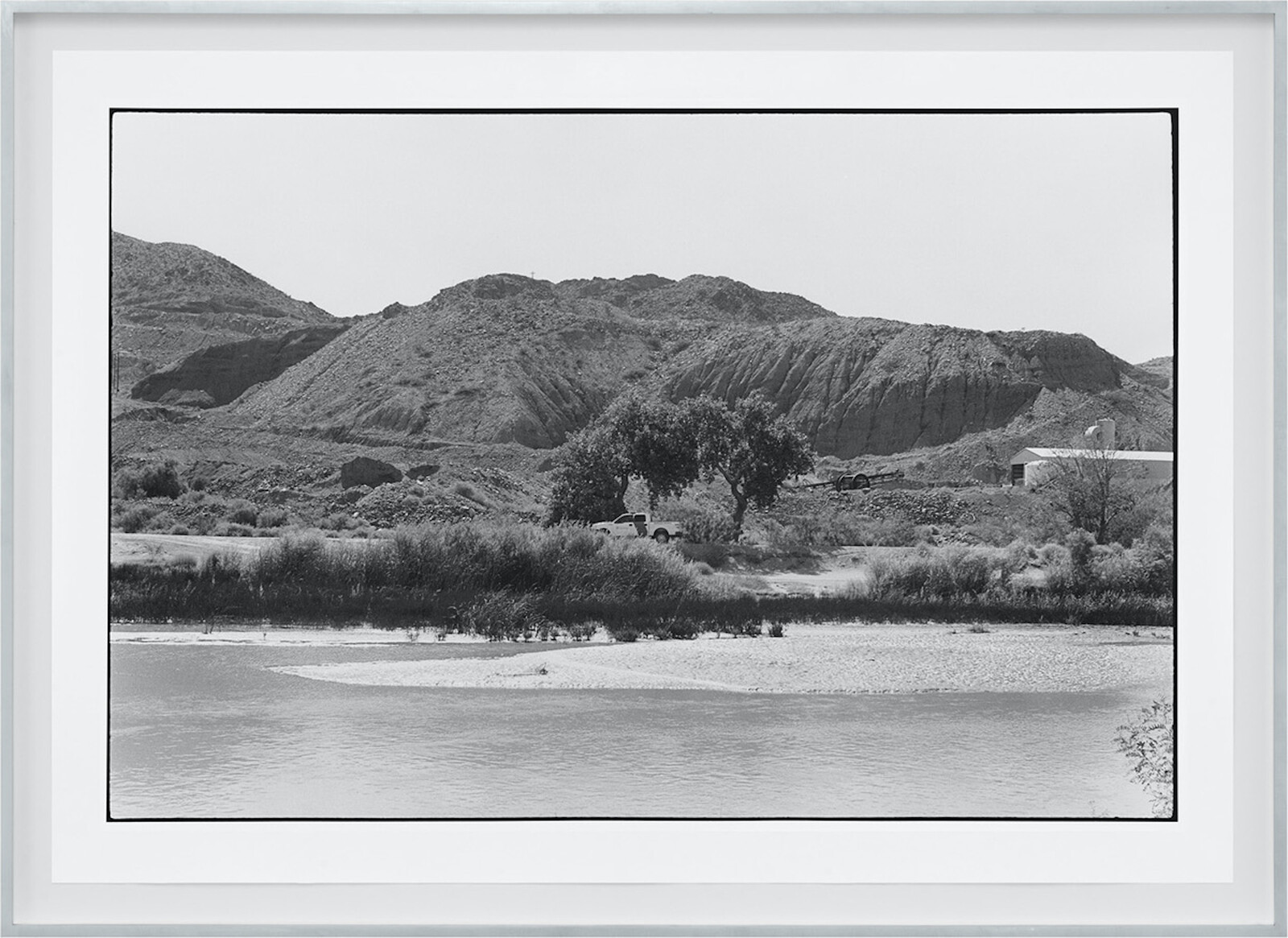

Jo Ractliffe’s “Landscaping”

Sean O’Toole

Jo Ractliffe has for decades been photographing the charged and ravaged landscapes of her native South Africa. For nearly as long, she has bristled at the insufficiency of the art-historical term “landscape” in encapsulating her interest in terrains where histories of occupation, use, conflict, and violence do not obviously declare themselves. Sometimes, and only partly in jest, she has used the term “blandscape” to characterize her abstruse images of nothing much in particular, be it a locked gate to an Apartheid-era torture site or desert landscape linked to a forgotten Cold War battleground. Last year, when Ractliffe was shortlisted for the 2022 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, she repeated this dislike, describing landscape as a “difficult term,” more descriptive of an outlook or prospect than a space or place. “I think of [landscape] less as a ‘subject’, or genre,” she adds, “than the medium through which I can explore questions of violence, conflict, and memory.”

Ractliffe’s new exhibition “Landscaping,” her first major statement since her 2020 survey exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, extends her interest in land as tangible fact and immanent subject. It is a remarkable career statement. Her thirty-four black-and-white photos, the majority taken over the …

October 27, 2023 – Review

Candice Lin’s “Lithium Sex Demons in the Factory”

Jonathan Griffin

The story, as literary theorist Peter Brooks has observed, is today’s dominant cultural form. To Brooks, this “overabundance” of narrative is worrying: he criticizes the deference of virtually all strands of culture (not only literature, TV, and movies but art, museology, and—especially—news media) to the persuasive rhetorical power of the story. I share many of his concerns. “The universe is not our stories about the universe,” he writes, “even if those stories are all we have.”

In the artwork of Candice Lin, however—an artist who nests stories inside stories, who researches, remembers, speculates, and concocts in equal measure, all at once, without hope or intent to persuade—the story becomes a lubricative medium that enables the destabilizing of sense, the de-centering of singular subjectivities, and the unpicking of neatly tied conclusions.

“Lithium Sex Demons in the Factory,” the Los Angeles-based artist’s multimedia exhibition at the non-profit Canal Projects in New York, is near-impossible to summarize, except by telling stories. Let me start with one. In the 1970s, female workers at Japanese-operated factories in rural Malaysia experienced demonic possessions and spirit attacks. Workers at these factories hailed not just from Malaysia but China and India too, so bomohs (Malay shamans) and healers …

October 24, 2023 – Review

Coco Fusco’s “Tomorrow, I Will Become an Island”

JS Tennant

It comes as no surprise that “Tomorrow, I Will Become an Island” opens with documentation of Coco Fusco’s Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West (1992–94): her justly famous performance with Guillermo Gómez-Peña, staged at the moment the world was tussling over how best to commemorate, or denigrate, the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s so-called “discovery” of the Americas. A prime benefit of the Cuban-American artist’s first major retrospective—curated by Léon Kruijswijk and Anna Gritz—is to be able to trace the arc of suggestive continuities within her impressive thirty-year body of work.

In Two Undiscovered Amerindians, Fusco and Gómez-Peña toured the world in a cage where they were displayed as “natives” of a recently discovered Caribbean island. A subsequent film, The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey (1993), captures this performance and reactions from the public, its footage intercut with a montage of real-life circus sideshows, world fairs, and racist “ethnographic” dioramas. Attendants, acting as ringmasters, invite passersby to interact with the couple, who speak no English. Bananas are fed to them through the bars; the “female” can be made to dance; five dollars grants a titillating fondle of the “male specimen’s” genitalia. The island’s name, Guatinau, would be pronounced, in …

October 16, 2023 – Review

Lin May Saeed’s “The Snow Falls Slowly in Paradise”

Jesi Khadivi

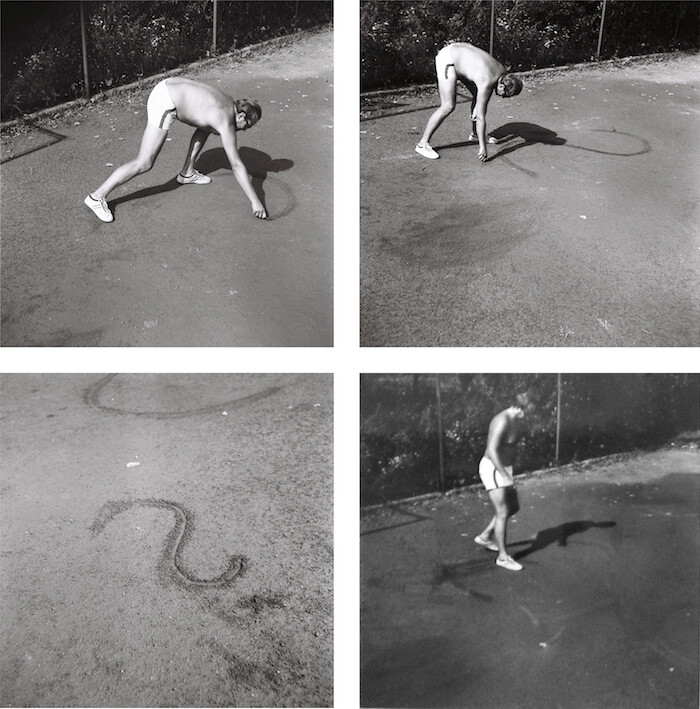

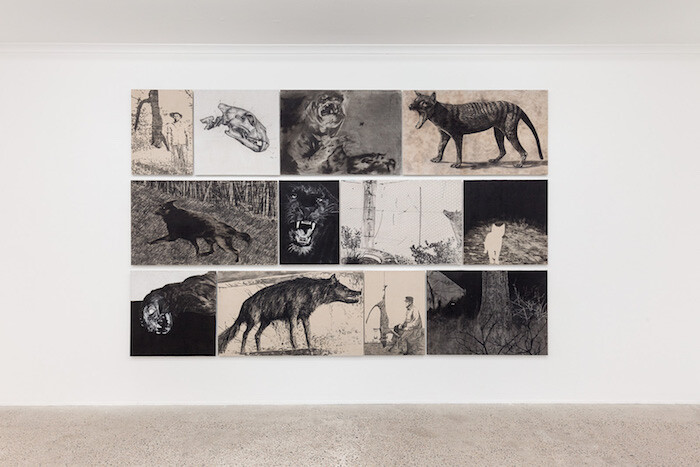

In What is Philosophy? (1991), Deleuze and Guattari write that “art is continually haunted by the animal.” Looking back through millennia of artistic production, we see representations of our beastly counterparts everywhere: as companions, deities, workers, or raw material. Likewise, John Berger has argued that “the parallelism of their similar/dissimilar lives allowed animals to provoke some of the first questions and offer answers.” Yet a life in common, and the reciprocal gaze that humans and animals once shared, was lost in the West with the development of nineteenth-century capitalism. The practice of German-Iraqi artist Lin May Saeed brings the image of the animal from the periphery back to the center.

Saeed devoted her life, sadly cut short by brain cancer at the age of fifty last month, to the cause of animal liberation. Her work avoids agit-prop depictions of animal suffering and instead draws on myths, stories, and fables so that we might “imagine a kind of time travel with a focus on the human-animal relationship” and “think about our common future” by looking at the past. “The Snow Falls Slowly in Paradise,” in which Styrofoam sculptures and reliefs, figurative wall works, drawings, and videos are shown alongside animal sculptures …

October 12, 2023 – Review

Steirischer Herbst ’23, “Humans and Demons”

Joshua Simon

In the opening speech for “Humans and Demons,” her sixth edition as curator of Europe’s longest-standing annual contemporary art festival, Ekaterina Degot stated that the exhibition “is not about good and evil” but “status quo and evil.” This distinction informs the four main exhibition sites and programs deployed through the city, organized according to the trajectories of three historical figures—and one object—to live or pass through Graz during or after World War II. These are represented in each venue by a curatorial research installation: a collection of records owned by Nazi officer and jazz enthusiast Dietrich Schulz-Köhn, alias Dr. Jazz (1912–99); the personal archive of physicist Stefan Marinov (1931–97); an AI rendering of the Zürich-born Brazilian artist Mira Schendel (1919–88); and a copy of a 1925 postcard showing pacifists holding a banner on which the word “Friede” (Peace) was later changed to “Frieda” to avoid Nazi persecution.

This year’s Steirischer herbst takes place against the backdrop of Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, among the many lessons of which is that we never really left the twentieth century. In that context, and in such a historically saturated exhibition, the above installations are a brilliant move. They free participating artists from archival …

October 11, 2023 – Review

Jota Mombaça’s “A CERTAIN DEATH/THE SWAMP”

Harry Burke

In the final chapter of her 2016 book In the Wake, Christina Sharpe meditates on the weather, which for her signifies the “pervasive climate” of antiblackness in the modern world. Her argument is shaped by the insight that “new modes of writing, new modes of making-sensible” are needed to account for the quotidian violence of the colonial present. Jota Mombaça’s “A CERTAIN DEATH/THE SWAMP” builds on these contentions through a series of artworks that address the weather and, when viewed together, make up an atmosphere.

While preparing for the show, Mombaça researched the disastrous flash floods that struck western Germany and neighboring countries in 2021, as well as Berlin’s origins as swampland, drained in the 1700s. What would it mean, the artist asked herself, for cities to turn back into swamps? until the last morning (2023), made in collaboration with Anti Ribeiro, Darwin Marinho, and Luana Peixe, is her oblique answer to this. The looping, fourteen-minute video studies the mangroves and marshlands of Pará in her native Brazil. Its long, pensive shots of clouds recall John Constable’s cloud studies of the 1820s. For the Romantic painter, clouds exteriorized emotions and symbolized modernity’s scientific advances. To today’s eye, they also refract …

October 6, 2023 – Review

“Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism”

Matt Shaw

In March 1949, the cover of Popular Science magazine featured Ray Pioch’s brightly colored drawing of architect Eleanor Raymond’s Dover Sun House, a Massachusetts home developed with solar engineer Maria Telkes and heated exclusively by solar energy. Part Rockwell painting, part architectural section, and part science diagram, the illustration drew on Pioch’s experience drawing instruction manuals for the U.S. Navy during World War II. It shows an idyllic family in their well-tempered living room, kept warm by the energy captured through south-facing windows and stored in canisters of mirabilite, or Glauber’s salt, a mineral well suited to storing solar heat in the day and releasing it after dark. The cover represents the best image of post-war Pax Americana, but with a twist: a bright optimism that the sun was the future source of America’s energy needs, not oil.