Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

March 20, 2024 – Review

Saskia Noor van Imhoff’s “Mineral Lick”

Tom Jeffreys

In 2021, Saskia Noor van Imhoff purchased a dairy farm amid the polder landscapes of Friesland in the Netherlands. The farm had been active for some four hundred years, but derelict for the past fifteen. van Imhoff approaches the site as a research project, entitled Rest, with the implication that the land, exhausted after centuries of extractive management, now finally has the chance to recover. With the land recuperating, the artist set to work: reactivating the farm not only as a site of agricultural production (prioritizing a certain conception of environmental responsibility over a profit motive) but also as a place for workshops, symposia, and other interdisciplinary activity. Meanwhile, van Imhoff has also reoriented her practice in response to the land, its historic uses and possible futures.

“Mineral Lick” is the first UK solo show for van Imhoff, whose previous work has focused on hierarchies of value within collecting institutions such as museums and archives. Here, she foregrounds unexpected material combinations underpinned by a fascination with grafting, hybridity, and the recontextualizing of materials. GRIMM’s street-level windows have been washed with white shading paint and the interior glows with pink-red light—both echoes of the forced growing conditions of commercial greenhouse production. …

February 2, 2024 – Review

Deimantas Narkevičius’s “The Fifer”

Michael Kurtz

The centerpiece of Deimantas Narkevičius’s current exhibition at Maureen Paley is a holographic screen—a small block of glass on a sleek metal shelf. A nightingale appears in the glass and lands on a branch that hangs there, while audio plays of a flute mimicking birdsong in sync with the movements of its beak. It flies out of view again and then returns, left and right, left and right. On an adjacent wall is another branch of sorts—a bark-like bronze cast of the cavities inside a flute—and nearby hang two small black-and-white images: a 1920s photograph from the Lithuanian State Archive of a soldier playing the flute by a window and a digital recreation of the same scene from directly outside the building. This perplexing constellation of objects is named after the shadowy figure in the photograph, The Fifer (2019).

Holography represents the height of illusionism, elaborately conjuring animated three-dimensional images. But the nightingale’s restless movement in and out of frame continually calls attention to the screen’s edges, where the projection falters and the empty glass block becomes visible. The illusion is further ruptured by the flutist’s birdsong which, isolated from any ambient sound, is unconvincing. Each item here performs a …

November 7, 2023 – Review

Lutz Bacher’s “AYE!”

Michael Kurtz

The first room of “AYE!” is carpeted with fine sand. Audio from Philip Kaufman’s 1988 film adaptation of The Unbearable Lightness of Being fills the air. “Tomas,” a woman asks between kisses, “what are you thinking?” To which Tomas replies: “I’m thinking how happy I am.” The clip loops—the lovers locked in this tender moment, accompanied by piano music and the thrum of rain and windscreen wipers—and with every repeat becomes more cloying and meaningless. Four television screens in a row to one side emit a white glow which fades each time the loop ends, an electronic sunset on the beach. There is a formal resonance between the artificially uniform texture of the sand, the blank monochrome screens, and the eternally recurring sweet nothings. In these elements—nature, entertainment, love—we seek comfort, but here find them in a state of entropy: metronomic, sterile, vacuous.

A child in red dungarees arrives at the door and points at me. “There’s a big man in the sandpit,” she announces to her father, getting his reassurance before dancing freely across the room. She writes her name in the sand, and in doing so shares something that the pseudonymous Lutz Bacher, who died in 2019, never …

October 20, 2023 – Feature

London Roundup

Chris Fite-Wassilak

“Celebrating 20 years,” ran the bus and magazine ads for Frieze London, keen to capitalize on having reached a milestone. In 2003, the first fair was welcomed as a galvanizing and creative force—a Studio International review from the time breathlessly described it as the “the real thing […] the apotheosis of swing […] the Stargate.” Such enthusiasm seems cute now, after the artist projects that supposedly set the fair apart from other trade events (Mike Nelson earning a Turner Prize nomination in part for his 2006 installation at the fair) have been scaled back almost to invisibility, and the “Focus” section for younger galleries, introduced in 2013, effectively assimilated parallel smaller fairs such as Zoo and Sunday. Of the 164 stand-holders at this year’s Frieze London, only 30 of them (predominantly, of course, the larger multi-venue galleries) were at the first 2003 fair. Through all this, the fair has long presented itself as an annual temporary institution, masquerading as such among the long-term underfunding of the city’s public museums.

This hoarding of resources has a distorting effect on coinciding and parallel events that would otherwise register as an alternative, both to the fair and other art spaces around London. Several …

September 12, 2023 – Review

Niklas Taleb’s “Solo Yolo”

Marcus Verhagen

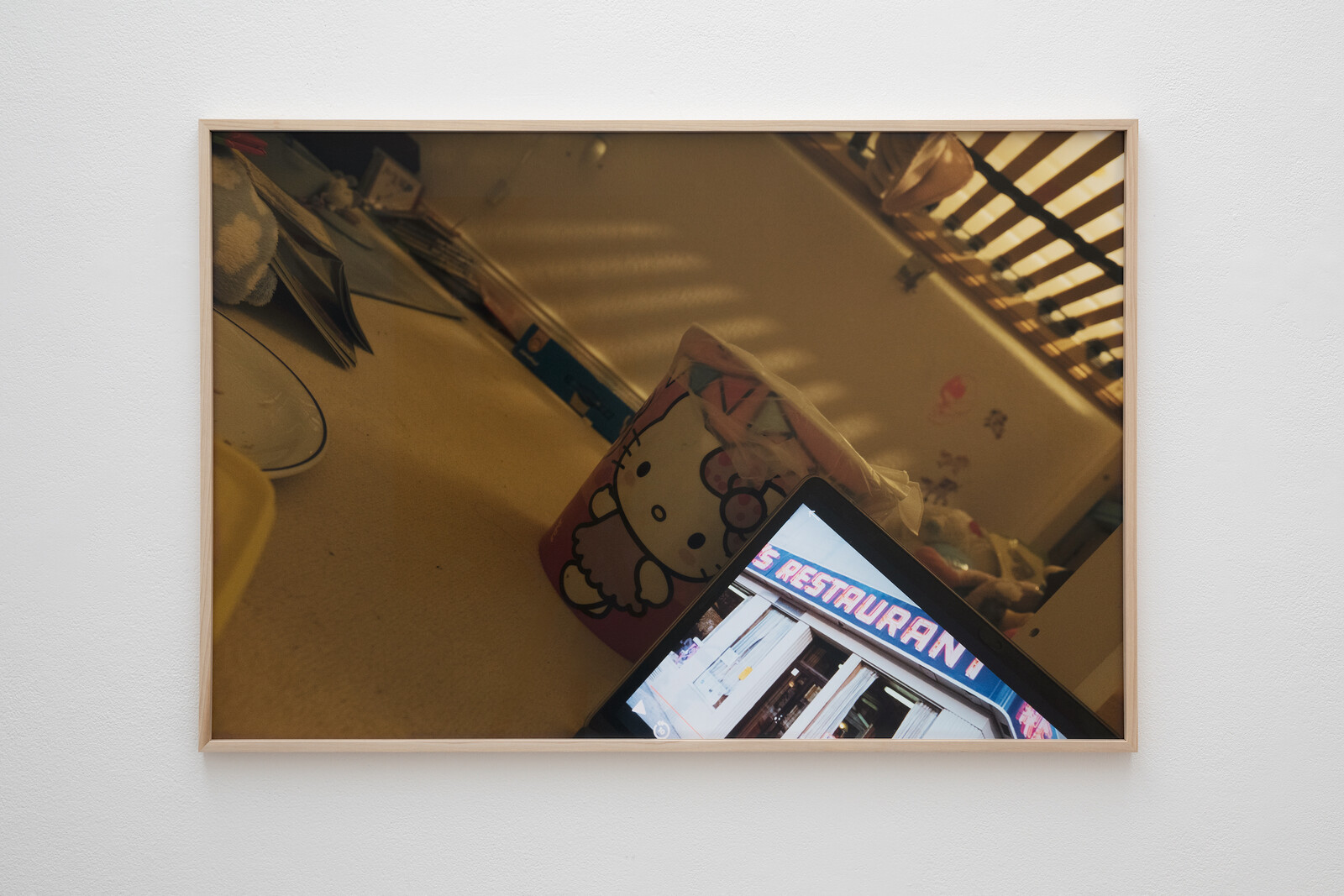

The photographs in the first UK show of the Essen-based artist Niklas Taleb describe intervals and cadences rather than people or events. In particular, they outline the rhythms of the home: most of them show the artist’s apartment, where, it would seem, time passes slowly. Arranged in a spare hang across the gallery’s two small-ish spaces, these are reserved images in which rooms feature more prominently than the family inhabiting them. Often untitled yet all dated 2023, they are populated by toys and crockery, computer screens, flowers, and mementos. The remains of a snack sit on a carpet, multicolored building blocks are balanced on the rim of a drawer, snapshots of relatives are tucked in the gilt frame of an old print. In their reticence, these glimpses into the day-to-day life of a household leave viewers to establish what narrative and thematic continuities they can.

The family itself is largely offstage. The shadow above the building blocks may be the artist in silhouette. Elsewhere, a woman, his partner perhaps, files an infant’s fingernails, but only their hands are visible. Social life makes a marginal appearance in two pictures of visitors absorbed in their own thoughts. In the liveliest scene here, …

July 13, 2023 – Review

Gelare Khoshgozaran’s “To Be The Author of One’s Own Travels”

Dylan Huw

Gelare Khoshgozaran describes herself as an “undisciplinary artist and writer.” Across her work, she harnesses the capaciousness and flexibility of the essay form to articulate the possibilities inherent in exile. Her 2022 essay “The Too Many and No Homes of Exile,” for example, articulates the “limbo” of a life marked by latency and anticipation. While it draws on the artist’s personal memories, its emphasis—as in much of her work—is on forming associations and fostering solidarity across contexts of displacement. “You look at the map of Los Angeles,” she writes of the city in which she now lives, “and identify a map of exile.”

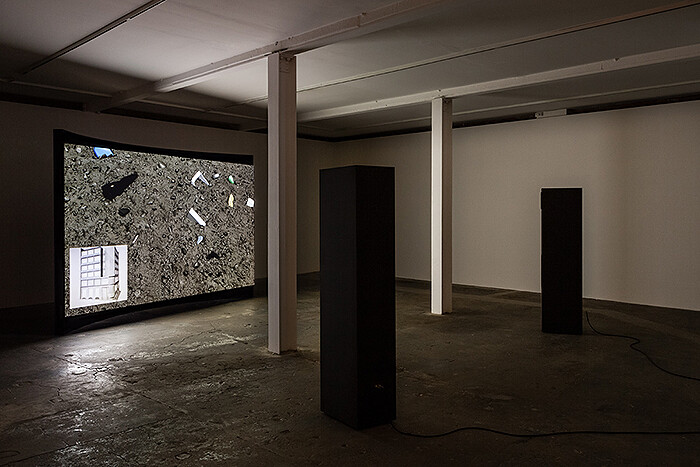

Her first solo exhibition in Europe, curated by Eliel Jones at Delfina Foundation’s cavernous central London space, features three moving-image works that reflect the lyricism and political intentionality of her written work. Born in Tehran in 1986, during the Iran-Iraq War, Khoshgozaran is particularly invested in making way for alternative, affirmative practices of living. She channels this wide-ranging understanding of exile into a methodology—and something approaching a narrative—in The Retreat (2023), the exhibition’s longest, loosest work.

Described in the press materials as “visual expansion” of Khoshgozaran’s 2022 essay, the film stems from an “exile retreat” organized by …

June 29, 2023 – Feature

London Gallery Weekend

Orit Gat

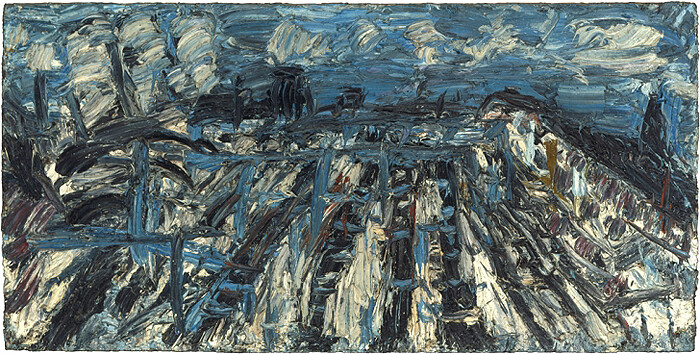

This year’s edition of London Gallery Weekend suggested something that initially surprised me: that the joy of seeing multiple shows in one weekend can be less in new discoveries than in meaningful re-encounters. Looking at Jadé Fadojutimi’s three-by-five-meter painting And willingly imprinting the memory of my mistakes (2023)—included in “To Bend the Ear of the Outer World,” an exhibition of contemporary abstraction curated by Gary Garrels at Gagosian—I thought, I still love this. I first encountered Fadojutimi’s work as part of the 2021 Liverpool Biennial; in this more formalist context I can see how the things I loved then—its blending of oil, pastel, and acrylic in one canvas, its massive presence—are in dialogue with painters I’ve been following for years. The invention and freshness of Laura Owens’s approach to painting is confirmed by every re-encounter; I continue to be amazed by how Charline von Heyl’s Circus (2022) evokes its colorful subject through abstract patterns of gray, black, and white.

Many galleries chose to dedicate their London Gallery Weekend shows to painting, and I loved many of the paintings on view. I was impressed with Shaan Syed’s four works at Sundy, which depict forms from the natural world—like the rubber plant—as …

April 18, 2023 – Review

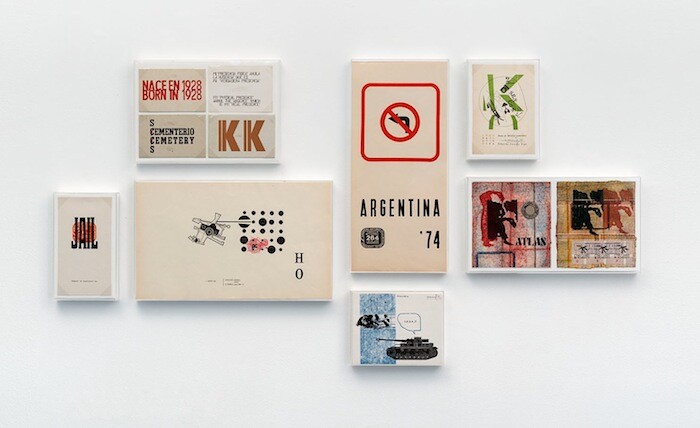

Raqs Media Collective’s “1980 in Parallax”

Patrick Langley

Charles Jencks was a pioneer of postmodern architecture—or “bastard classicism,” as his American detractors put it. In 1979 the American-born polymath and his wife, the garden designer and historian Maggie Keswick Jencks, purchased a large townhouse in London’s Holland Park and extensively redesigned it over the next five years. At once a family home and a “built manifesto,” The Cosmic House nods to Ancient Egyptian, Baroque, and Hindu architecture, modern science and urban planning, the Zodiac, western philosophy, and much else besides. Jencks integrated his eclectic references into a rich (and kitsch) symbolic scheme that sought to reconcile micro- and macrocosms: domestic pleasures and cosmic immensities; private gags and philosophical traditions. A cantilevered spiral staircase at the center of the building, for example, doubles as a model of the solar year with fifty-two steps for each week; at its base is Eduardo Paolozzi’s circular mosaic Black Hole (1982).

Leading off from this mosaic is the basement gallery, home to an elegant exhibition by New Delhi-based Raqs Media Collective. (Jencks was co-designing the gallery with his daughter Lily until his death in 2019; the museum opened to the public two years later.) Founded in 1992 by Jeebesh Bagchi, Monica Narula, and …

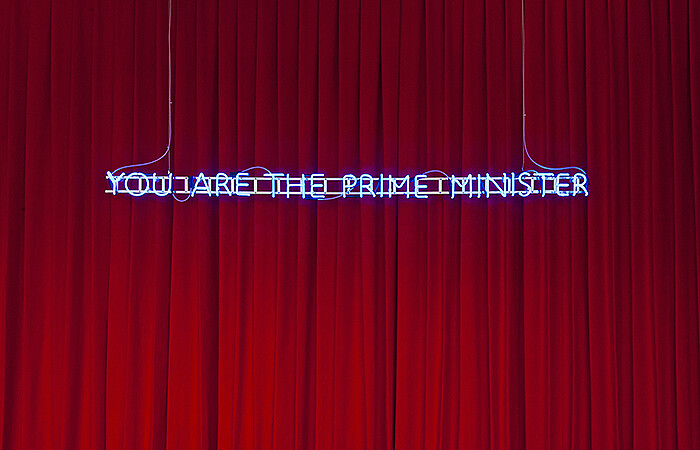

March 10, 2023 – Review

“People Make Television”

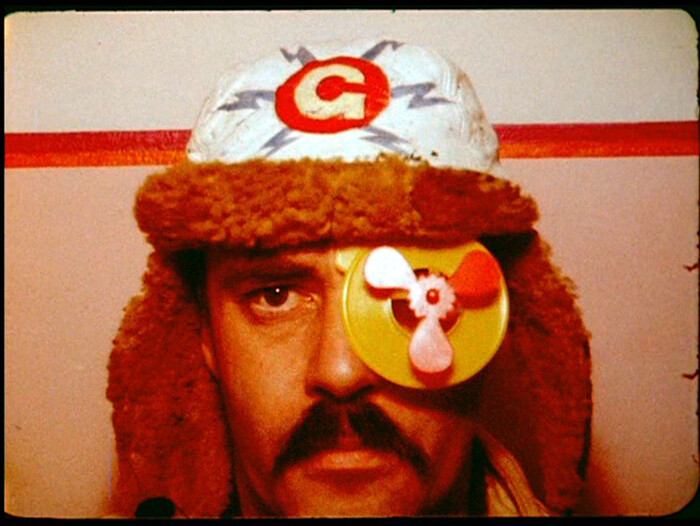

Brian Dillon

For much of its century-long history, the BBC has been an object of nostalgia in Britain. It began as a private company, and in 1927 a royal charter decreed its mission to “inform, educate, and entertain” the nation; the corporation is funded today by a television license levied on all households that watch its output. The public-service remit always appears to have been better fulfilled in the past, during a vague and movable golden age. Public service, of course, has rarely meant public access or participation. An exception was the work of the Community Programme Unit, which in 1972 began soliciting program ideas from interest groups and campaigning organizations. Around three in ten proposals were accepted; successful applicants were then provided with a small budget, a production team, and a final say in the show’s edit—subject to legal niceties and the BBC’s sometimes vexing commitment to “balance.” Copies of the finished programs were given to the groups who devised them, but most were never broadcast again. “People Make Television,” an absorbing exhibition at the newly reopened Raven Row, includes over 100 of the CPU’s programs (alongside other public-access projects of the time), and seems to conjure a genuine lost era …

January 10, 2023 – Review

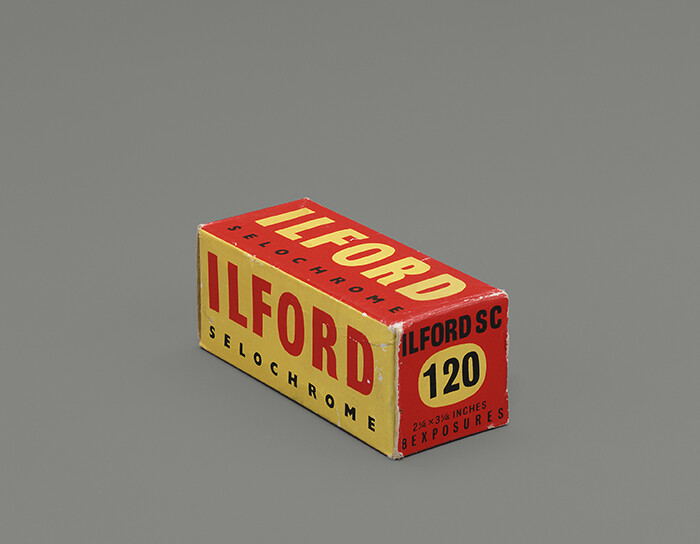

Aarati Akkapeddi’s “A·kin”

Michael Kurtz

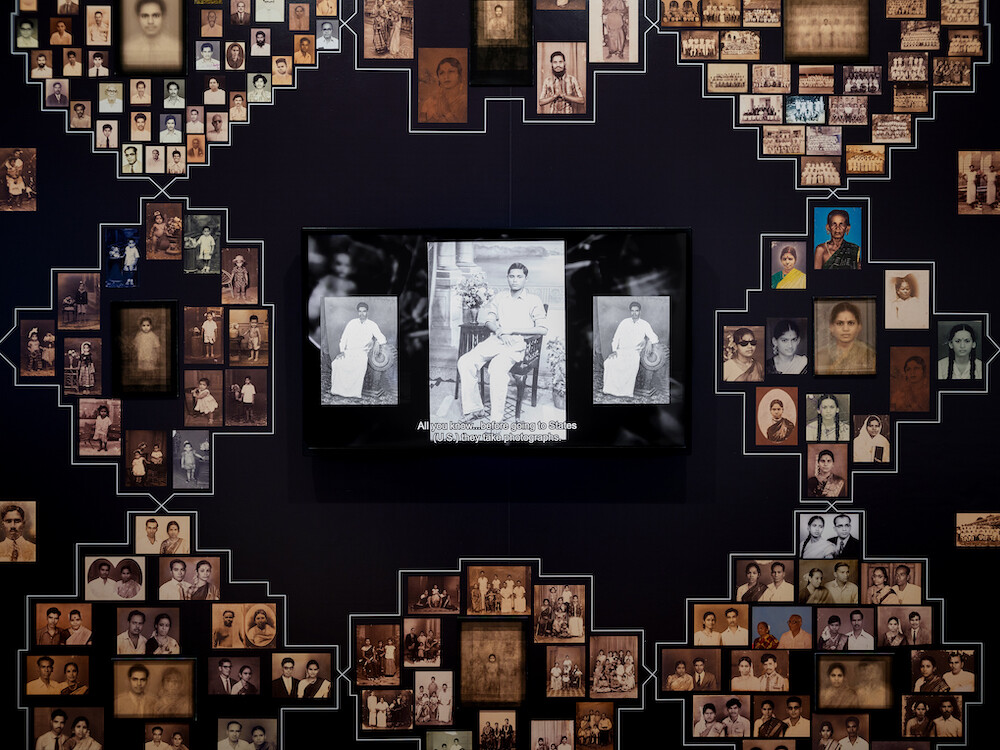

Aarati Akkapeddi’s work exploits the uneasy interaction of analog and digital—paper and pixels—to convey the strangeness of both our warped view of the past through dog-eared images and the mediation of the present by algorithmic technologies. “A·kin,” at London’s Photographers’ Gallery, continues the Telugu-American artist and programmer’s practice of using machine-learning algorithms to analyze and manipulate historical images.

The installation combines Akkapeddi’s family photographs from the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu with those from an archive created by the STARS research collective of Tamil studio photography from the 1880s to the 1980s. Akkapeddi used an image classification model called VGG-16 to sort the photographs into a grid based on formal similarity, and then divided them into twelve generic groups: portraits of children propped up by an object, for instance, and close-ups of couples in which the man stands on the left. These “clusters” are arranged across a gallery wall within the interlocking forms of a kolam—a pattern drawn with rice flour at the entrance of Tamil homes to bring good fortune and exclude evil spirits. A larger composite image at the center of each group collates the surrounding photographs as if to identify what they share, while interviews …

November 4, 2022 – Review

Olivia Plender’s “Our Bodies are Not the Problem”

Tom Jeffreys

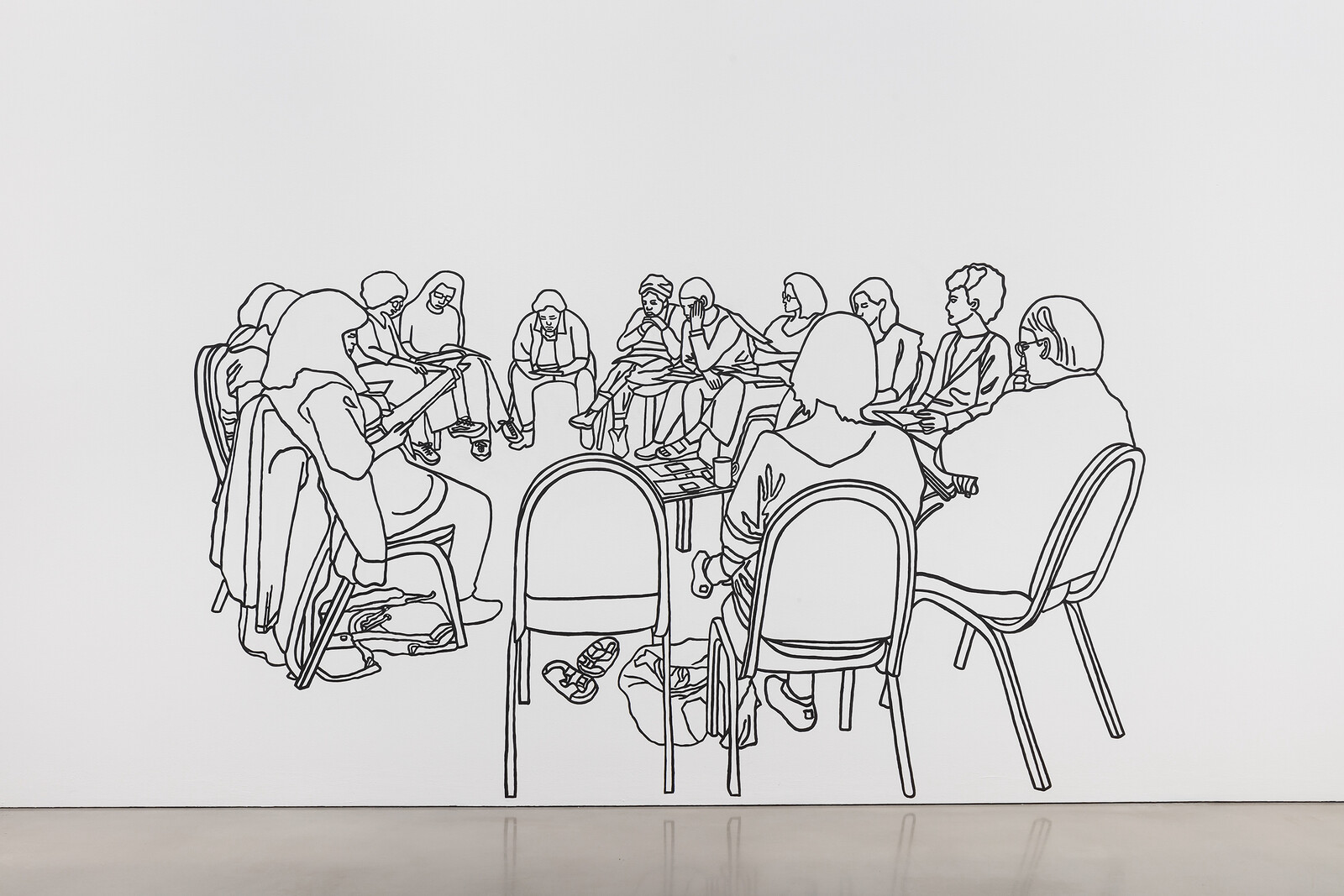

Olivia Plender’s research-driven practice is rooted in a fascination with the way communities self-organize—from activist groups, youth movements, and spiritualist associations to alternative education programmes and the offices of tech behemoths—and the strategies, labor, geographies, and architectures that enable (or obstruct) them. Her second solo exhibition at Maureen Paley recontextualizes texts, images, and actions relating to self-education and resistance, with the delicacy of several series of small drawings in black ink or charcoal pencil contrasting with all-caps wall posters proclaiming statements like “THEY WILL NOT DIVIDE US.” But in bringing together these slices from various projects, each of which has grown out of sustained historical research or community engagement, this exhibition is not always successful in communicating their richness or significance.

Plender takes great care in considering the spaces in which community organization takes place: she pays attention, for example, to the labor that goes into setting up for a meeting or tidying away afterwards. In 2021, she revamped the community room at Glasgow Women’s Library, transforming the upstairs area into one of welcoming softness. Plender’s life-size drawings are now emblazoned across a partitioning curtain. Floor rugs and jewel-toned bean-bags offer comfort for those wishing to sit or lie, while …

May 20, 2022 – Feature

London Roundup

Orit Gat

In the local elections held the week before London Gallery Weekend, the residents of Westminster City Council, which covers much of central London, voted Labour into a majority for the first time since the council’s creation in 1964. The vote was partly informed by the Conservative council’s misguided decision, widely publicized in 2021, to spend six million pounds on the “Marble Arch Mound,” a twenty-five-meter-tall astroturf hill and viewing point designed to lure viewers back to the city’s busiest shopping district. It failed: many stores are still covered with for-rent signs, one of which peddled a “blank canvas for new ideas.” These are the visual and linguistic relics of the before-time: they represent old ideas of urban environments and their inhabitants’ habits, and beg the question, “What if we don’t want to return to how things were?”

At Emalin, Augustas Serapinas is displaying eight large black reliefs made of roof shingles taken from a wooden house from his home country, Lithuania. Many of these traditional architectures are now abandoned or destroyed and used for firewood. Serapinas bought one, broke it apart, charred its roof shingles, and repurposed them into monochromes that are part-painting, part-sculpture. They are heavy, loaded with their …

April 14, 2022 – Review

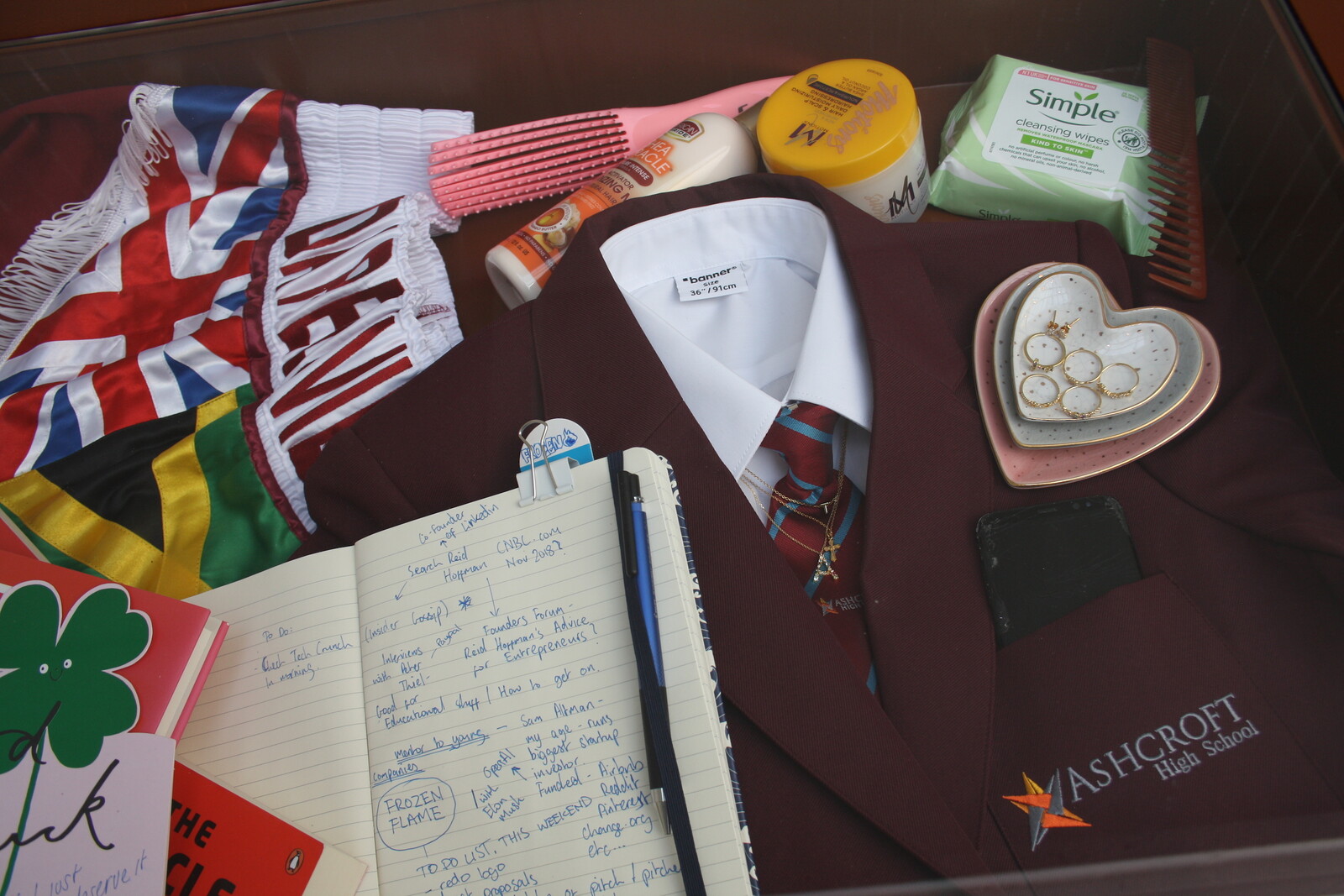

Patrick Goddard’s “Pedigree”

Tomas Weber

Watching animals in a zoo, Patrick Goddard’s show at Seventeen suggests, disapprovingly, is a bit like looking at art in a gallery: you stroll between marvels, whose only reason for being is to be seen. At the entrance to the gallery are three grisaille ink paintings (all 2022) behind reeded privacy glass. Each stars a bichon frise dog: watching a burning car (Whoopsie at the End of the World), saying “up against the wall!” through a speech bubble (Whoopsie, Up Against the Wall), and next to a naked woman under the word “APOCALYPSE” (Whoopsie’s Dream). Against the quietness of these works on paper, a sculptural installation occupies a whole wall. Plague (Downpour) (2022) consists of 200 falling frogs cast in recycled lead and attached to the wall. Each is unique, its body caught in baroque contortions: some graceful, some agonized, some resigned. These works introduce the show’s prevailing theme of our entanglements with animal life, from pets to pests.

Humans enlist animals into satisfying their needs and desires. Sometimes such animals are threatening or toxic; usually, they are unfathomable. As John Berger points out in “Why Look at Animals?,” a 1977 essay that inspired Goddard, animals have been stripped of …

March 10, 2022 – Review

Every Ocean Hughes’s “One Big Bag”

John Douglas Millar

In the introduction to her friend the photographer Peter Hujar’s monograph Portraits in Life and Death (1976), Susan Sontag wrote that: “We no longer study the art of dying, a regular discipline and hygiene in older cultures; but all eyes at rest contain that knowledge. The body knows and the camera shows inexorably.” Sontag wrote those lines from a hospital bed while awaiting surgery to remove a malignant tumor from her breast. The surgery was successful, but she would die from cancer a quarter century later, terrified, furious, and absolutely unresolved.

On June 5, 1981 the first clinical report on AIDS was published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. In the years that followed, the gay and queer communities and other vulnerable minorities were forced to “study the art of dying,” to construct communities of mourning and activism and develop clusters of “lay-expertise” in pharmaceuticals and their trialing, endocrinology, blood science, and the legal and ethical structures of the medical and death industries. As the art historian and ACT UP New York member Douglas Crimp argued, “AIDS intersects with and requires a critical rethinking of all of culture: of language and representation, science and medicine, health and illness, sex and …

March 4, 2022 – Review

Jala Wahid’s “AFTERMATH”

Adeola Gay

Delicate sheets of paper are scattered over the floor of Jala Wahid’s exhibition at Niru Ratnam Gallery. The pieces are reminiscent of leftover protest flyers and posters, giving the sense that a demonstration has taken place. The Kurdish-British artist’s exhibition continues her interest in exploring materiality, investigating the symbolic elements of archival objects. Wahid’s latest series of works is heavily informed by her research at the Kurdish Cultural Centre and the UK National Archive in London. The two archives focus on contrasting aspects of Kurdish history, with the former dedicated to the lived experiences of the Kurdish community, and the latter serving as a public record, listing details of treaties, conflicts, and political policies.

“Aftermath” is a collection of seven compelling objects and texts, with two sculptures hung on the wall, two sculptures placed on a long base, two text pieces displayed on plinths, and the paper cut-outs spread across the gallery floor. The exhibition prompts questions including: Who is allowed to narrate history? How does one document that history? And, most importantly, how are cultural identities formed? As with much of Wahid’s work, these recent pieces embody a sense of memory. The artist captures moments of conflict and …

February 8, 2022 – Review

Donna Huddleston’s “In Person”

Chloe Carroll

If you had been wandering the corridors of the National Institute of Dramatic Arts, Sydney, sometime around the year 1997, you might have happened upon a young, overworked Donna Huddleston. The artist documented her experiences studying set and costume in the monumental 2019 work The Exhausted Student, in which a pale waif, having fainted, is held aloft by a group of concerned, impeccably dressed undergrads in a sling of milky green drapery, pieta-like. Informed by Huddleston’s student years, the artist’s first exhibition at London’s Simon Lee Gallery stages a one-woman show over eleven unabashedly theatrical new works on paper. The drawings here mark a departure from The Exhausted Student’s tableau form, instead focusing in on strange intimacies and individual dramas.

Several pieces show the artist herself, roughly life-size, donning various glamorous disguises: slinky, ruched dresses with plunging necklines; ruffled poet’s blouses under tailored camel coats; immaculately coiffed wigs. She slips from frame to frame like a woman on the run. Most are rendered entirely in Caran d’Ache pencil, a painstakingly slow process and unforgiving material which lends itself naturally to the artist’s taste for minute detail against flat, overlapping planes and tightly choreographed mise-en-scene. Blocks of color are lightly flecked with …

February 4, 2022 – Review

Allison Katz’s “Artery”

Oliver Basciano

Why did the chicken cross the road? I don’t know—but Allison Katz has some suggestions. There are chickens aplenty in “Artery,” a show of 30 works, the majority new, by the Canadian painter. The other side (2021) is a painting of a cockerel in motion that recalls Eadweard Muybridge, the work hung across two freestanding walls so the bird seems to be surmounting the gap between them. Grains of rice—a kind of chicken feed, presumably—are scattered across the canvas surface, stuck on and around the golden animal. Despite the bird’s strut, it’s unclear—given the yellow plumage and blue-feathered head—whether what we are looking at is the result of Katz painting a chicken (or a photo of a chicken), or of her painting a chicken-shaped ornament; whether this painting is a representation, in other words, or a representation of a representation.

This quandary seems answered in The Cockfather (2021), a painting titled like a hipster fried chicken joint, but which in fact shows a kitschy egg holder in the shape of a cock in which are placed three eggs, the neck of the apparently misgendered bird (it is hens who normally warm eggs) forming a handle. This plumed porcelain soul …

November 4, 2021 – Review

Hurvin Anderson’s “Reverb”

Kevin Brazil

The first painting you see on entering Thomas Dane’s white-cube gallery—one of the two Duke Street spaces devoted to Hurvin Anderson’s “Reverb”—is called Skylarking (all works 2021). In a two-meter tall canvas, three small figures stand in the lower foreground. A woman, to the left, looks away from the viewer. Another, in the middle, looks to the right, partially obscuring the face of a man standing behind her. Are they looking at one another? Conversing? Above loom palm trees in bursts of dark green, aquamarine, and lime—above, albeit only on the surface of a canvas. The size of the trees in relation to the diminutive figures makes it hard to situate both in a coherent three-dimensional space, one which further dissolves in the lower half of the canvas as the paint thins into long thin drips. In their frozen interactions, and in their relationship to the trees, these figures are at once proximate and distant; almost touching, yet floating in unarticulated space.

This sensation of proximity and distance is produced by all the paintings in this show, even when, as is more common, no human figures appear. Each work, rendered in oil, depicts a hotel complex in northern Jamaica, where Anderson’s …

July 8, 2021 – Review

Tursic & Mille’s “Strange Days”

Kevin Brazil

Tursic & Mille’s Blue Monday (January) (all works 2021), an oil painting on a wood panel, depicts a young woman in a gingham dress sitting at a table. She is staring with confused disgust at her fingers, covered in the blue paint that lies, in a viscous blob, on the surface in front of her. Or rather, on the surface of the wood panel. Or rather: both on the table and on the panel at the same time, for the blue is so thickly applied that, disrupting the illusion, it reminds us that a painting is always matter and representation at once. Like this girl, Tursic & Mille are transfixed by this fundamental fact about painting: a fact and a fixation, which seems to unsettle as much as it captivates.

Each painting in “Strange Days,” Tursic & Mille’s first UK solo show, has a month of the year as a subtitle. These works, along with two sculptures of painted dogs, were all painted in 2021, yet the calendar they constitute serves as a summary of the concerns that the Serbian artist Ida Tursic and the French Wilfried Mille have explored since beginning to work together in the early 2000s. They start …

June 28, 2021 – Feature

London Roundup

Orit Gat

It would be impossible to think about London’s first Gallery Weekend in early June outside the context of the slow re-emergence from lockdowns. I know this strange sensation is not unique, but the experience of a public disaster dealt with largely by isolating from society has also marked the way I look at art. Taking stock of my tour of the city, it strikes me that the artworks which affected me most were ones that displayed intimacy, proximity, and all those daily exchanges from which I have felt distant these past sixteen months.

That is not to say that the daily and intimate are not political. At Lisson, “An Infinity of Traces,” a group show curated by Ekow Eshun, focused on the work of UK-based Black artists. It included Alberta Whittle’s video Between a Whisper and a Cry (2019), which explores Barbadian poet and historian Kamau Brathwaite’s idea of an oceanic worldview in the aftermath of the Middle Passage, and a series of watercolor text drawings by Jade Montserrat (who also has a solo show at Bosse & Baum in South London) that bear heavy, physical messages, like The smell of her still burning hair (2017). When I was trying to …

May 21, 2021 – Review

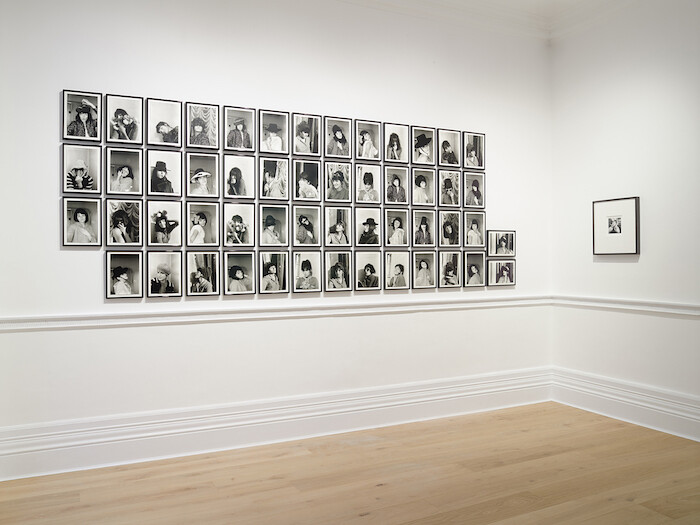

Peter Hujar’s “Backstage”

John Douglas Millar

“Backstage” is the third solo exhibition of Peter Hujar’s work to be presented at Maureen Paley’s London space since 2008, when the gallery took responsibility for the artist’s estate in the UK. The work is presented across two rooms; a larger space that almost exclusively shows portraits of artists from New York’s thriving drag performance scene of the 1970s, either preparing their costumes and make-up or gloriously composed backstage. These silver-gelatin prints were made by Hujar himself, with three exceptions: a portrait of the filmmaker John Waters, another of his muse Divine, and a group self-portrait showing Hujar jumping in the air with friends. These are all estate ink prints made by Gary Schneider, the artist and master printer trained by Hujar and now widely regarded as one of the finest printmakers alive. He is also the only printer authorized to make editions of Hujar’s work.

The second, smaller room displays four further estate prints: an extraordinary nude self-portrait entitled Seated Self-Portrait Depressed (1980); a portrait of Hujar’s friend the writer and raconteur Fran Lebowitz reclining in bed at her parents’ home in Morristown; one of Hujar’s sometime lover, protégé, and friend, the artist David Wojnarowicz, sparking up a cigarette on …

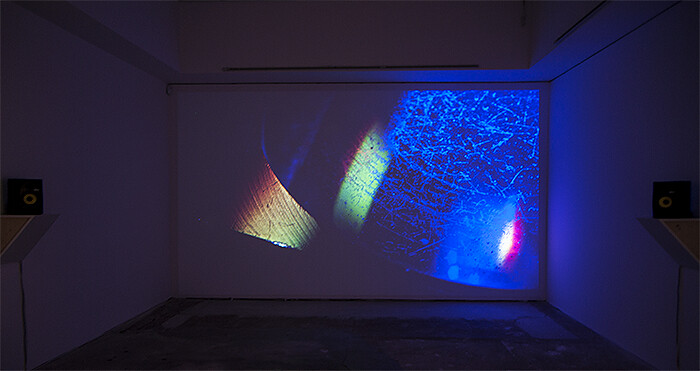

May 10, 2021 – Review

John Akomfrah’s “The Unintended Beauty of Disaster”

Cora Gilroy-Ware

Viral videos, especially those featuring animals, rarely make a lasting impression. Part of their charm is their innate forgettability. But every now and then there is an exception. In April I came across a video online that has haunted me ever since. Shot by drone from directly above, this 49-second clip centers on a strange spiral made up of hundreds of tiny gray-brown forms moving clockwise over a pale surface. As the camera moves down, we see that these forms are four-legged creatures whose fur ranges from dark taupe to a white brighter than what gradually reveals itself to be snow under their hooves. When the camera retreats back up into the sky, we glimpse another, more dense and fast-paced spiral to the left. A caption states that these are “reindeer cyclones” captured on the Kola Peninsula, the north-eastern part of the area known as the Baltic Shield. Responding to an outside threat, reindeer gather and move in a whorl, keeping their fawns tucked safely in the middle. In the comments under the post, viewers asked what, in this instance, caused the reindeer to behave in this way. “Probably the drone” was the consensus.

Not only were these mesmerizing rosettes …

April 20, 2021 – Feature

London Roundup

Patrick Langley

London’s galleries are open again. Exhibitions that were paused or postponed last fall have emerged from enforced hibernation into a cultural environment altered by six months of—well, not very much. To a quarantine-addled critic, this presents a quandary. One of the pleasures—and pitfalls—of writing about art is using it as a measure of lived experience: of holding work up to the light and saying, ah yes, this reminds me of something. The problem is, I haven’t much new experience against which to gauge the work. But maybe I’m not alone. In the capital’s galleries I kept noticing pieces, many made over this past year, that described a version of the same space—an unstable interior, variously possessed and infiltrated by outside forces. Which is to say, a state of mind. Or was I just projecting?

Leidy Churchman’s “The Between is Ringing,” at Rodeo’s Bourdon Street space, is a small, rewarding show of a dozen new paintings that range from smudgy abstraction to cartoonish exuberance. The work subtitled Diptych (all works share a main title with the exhibition and are dated 2020) comprises two oil-on-linen paintings, stacked one atop the other, depicting an abstracted living room that is also an existential void. The …

January 14, 2021 – Review

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s “Fly in League with the Night”

Caleb Azumah Nelson

In the foyer outside Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s exhibition, a question is written on the wall. “What sounds can you hear when you look at the paintings?” Music spills from a hidden speaker; Miles plays. I can hear the way he held his horn, so closely attuned to the spaces he could inhabit within a melody, perhaps looking for a nod from his band, or, more likely, improvising, always improvising. Feeling rather than knowing.

When I enter the space, it is quiet. The music has stopped, but looking at the paintings around me I still hear Miles and Bill and Gil, Fela and Ebo, Solange and D’Angelo: the music Yiadom-Boakye had playing in the studio when painting. A tradition of rhythm rendered on canvas in blues and greens, yellows and reds. In this way, it is possible to see something and to hear it too, and I wonder if this is what feeling is.

What I do see: Black figures, in all manner of poses and activities, caught in private moments. They tease and taunt, they are in repose, they squat, they crouch, they hurt, they ache, they joy. They are quiet but never silent. In Later or Louder or Softer or Sooner …

November 5, 2020 – Review

Bruce Nauman

Kevin Brazil

Even before you enter Tate Modern’s Bruce Nauman retrospective, you are put on edge. Approaching the galleries, you hear a man and woman shout “I hate, you hate, we hate!” from the screens of Good Boy Bad Boy (1985). As you queue at the exhibition’s entrance, Setting a Good Corner (Allegory & Metaphor) (1999), a video of Nauman erecting a wooden fence, assaults you with the nerve-shredding sound of a chainsaw. These sounds are deeply discomforting, but that which makes you uncomfortable is also that which you cannot ignore. Discomfort makes you aware of your own body: the unease caused by screaming, or the grinding of a saw, manifests in the tensing of muscles. Yet discomfort, in never becoming unbearable, induces self-reflection: you remain aware of what unsettles you and why. Attentive, aware of one’s body, reflective: discomfort shares much with how we think we should experience art. Why then does it feel so bad?

Discomfort as a state of awareness, this retrospective reveals, has been one of Nauman’s consistent preoccupations across six decades of work. Much has been made of Nauman’s exploration of media after Conceptual Art; many have traced his influence on later artists. Yet Nauman’s achievement …

October 9, 2020 – Feature

London Roundup

Chris Fite-Wassilak

It’s an unlikely benediction: two identical photos frame Dozie Kanu’s exhibition “Owe Deed, One Deep” at Project Native Informant: a small, slightly blurred image of a tower with a hand at the top, reaching awkwardly towards the sky. Emo State (2020) seems to have been taken from a moving car, the landscape around it giving some sense of the sheer scale of the tower, a religious monument modelled on the tower of Babel in southern Nigeria, constructed only a few years ago and torn down in 2019. The ghost of this demolished structure, the two hands waving over the five sculptural assemblages gathered below them, casts the works as their own temporary monuments, momentary markers to whatever spirit or feeling has possessed us, before disappearing. In a corner, St. Jaded Extinguish (2020) is a gray fire extinguisher stand placed forlornly on a flimsy, short set of black stairs, a bottle opener attached to its base that spells out a nihilistic mantra: “SELF SERVE.”

Making my way around exhibitions for the first time since February, it was such slight, haunted gestures that stuck with me. It feels disconcertingly normal to traipse around the city at this time of year, albeit with pre-booking …

September 24, 2020 – Review

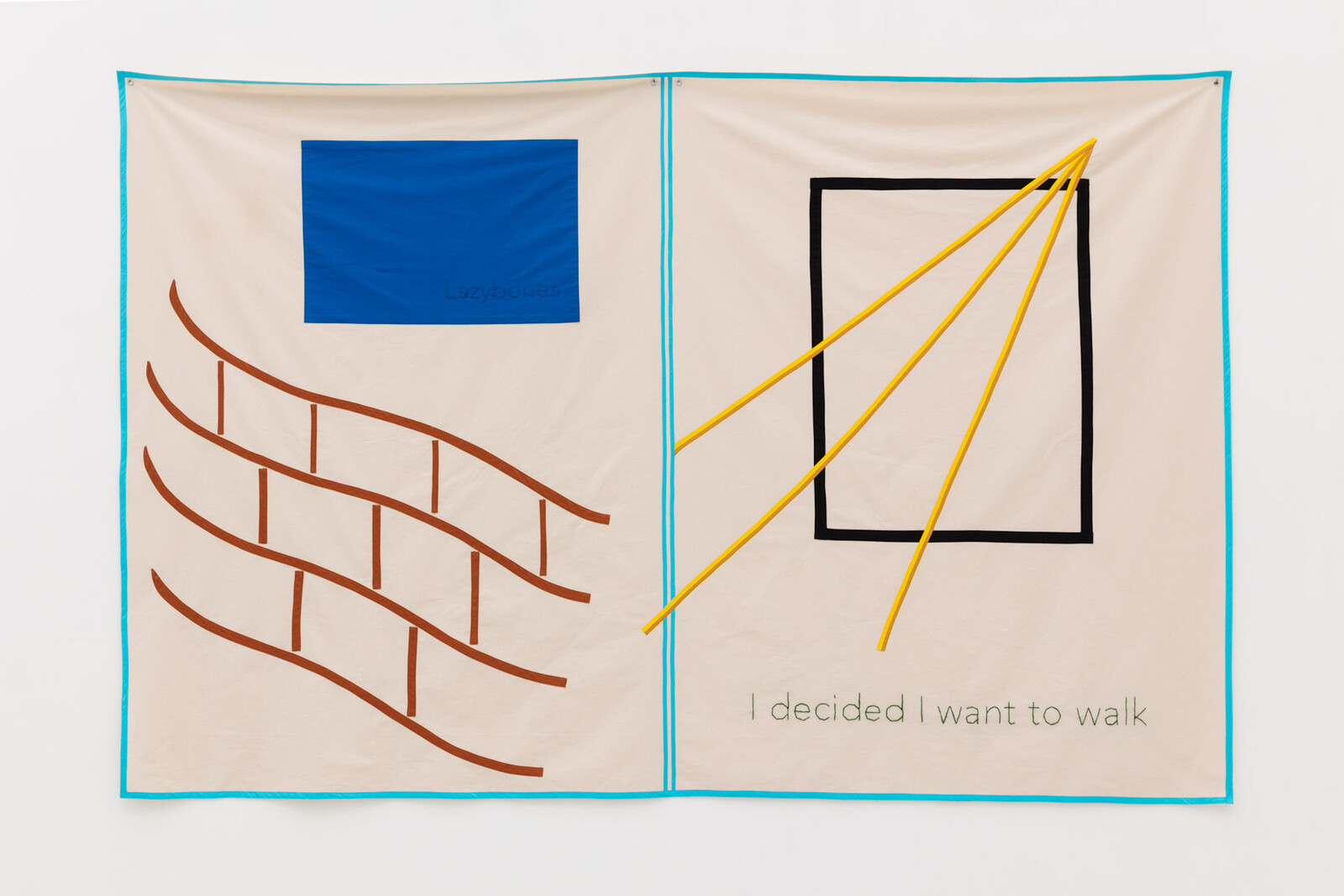

Helen Cammock’s “I Decided I Want to Walk”

Chloe Carroll

Helen Cammock’s 19-minute video They Call It Idlewild (all works 2020) presents, in no particular order, the static framing of: a brick wall, a statue, a frayed cobweb, grasses dipping in the breeze. The result of a pre-lockdown residency at Wysing Arts Centre, it’s the first piece encountered by visitors to “I Decided I Want to Walk,” the artist’s first solo exhibition at Kate MacGarry in London. The video’s imagery documents a space of retreat in rural Cambridgeshire, overlaid with a voiceover in which the artist ventriloquizes writers including Audre Lorde, Mary Oliver, and James Joyce.

Beyond the compact screening room at the exhibition’s entrance, two printed billboards (originally installed at a short-lived March exhibition at Wysing) line the walls of the light-filled main gallery, interspersed with a selection of new screenprints. Both series feature irregularly spaced white text against a monochrome background (crying/ is/ never/ enough; We/ Shared/ the/ Colour/ of/ Thought), and endeavor to rewrite the narrative of laziness, and to question its motives. Who is entitled to idleness? Who is expected to maintain productivity? For whom, in this moment, is idleness an applauded civic duty, and for whom is it a shirking of responsibility? Across the exhibition, …

July 24, 2020 – Review

Hannah Black’s “Ruin/Rien”

Harry Burke

A 2001 paperback edition of The Black Jacobins (1938), C. L. R. James’s study of the dialectical relationship between the Haitian and French revolutions, rests on a plinth in Hannah Black’s exhibition “Ruin/Rien” at Arcadia Missa (Ruin II, all works 2020). Its cover features a detail of Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson’s romanticist 1797 portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley, a freed slave who attained the rank of captain during the rebellion and was the first Black deputy elected to the French National Convention. The artist has placed a post-it note on the upper-right corner of the cover. Written on it, in yellow pastel against a blue background, is the word “RUIN.”

By revealing that the Haitian rebellion—which overthrew French colonial rule in one of the most consequential slave uprisings in history—was central to the upheavals in Paris, James argues that the question of slavery underwrites modern definitions of liberty. “Ruin/Rien” features a heterogeneous suite of new sculptures and videos that draw connections between these revolutionary events and the idea of the autonomous artwork. The bricked-up window of Bastille, for example, references both minimalist sculpture and the Bastille cell in which the Marquis de Sade was imprisoned and where he wrote The 120 Days …

July 15, 2020 – Review

Marc Camille Chaimowicz’s “Paintings…”

Cora Gilroy-Ware

As clichéd as it seems today, the association of pink and blue with girls and boys is a relatively recent notion. In both style and color, infants’ clothing was largely gender-neutral as recently as the early twentieth century, and it was not until the 1980s that the pink/blue code was fixed to the gender binary. Almost two centuries earlier, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe projected multiple tints and shades onto girls and women: the “female sex in youth,” he writes in Zur Farbenlehre [Theory of Colors] (1810), “is attached to rose-color and sea-green, in age to violet and dark green.”

The alignment of color with gender now seems antiquated. Yet as I walk into “Paintings…,” the latest installation by Paris-born, London-based artist Marc Camille Chaimowicz, I cannot help but notice precisely the feminine palette Goethe described. Rose, sea-green, and violet, with passages of darker green to offset the paler shades, proliferate throughout Cabinet’s exhibition space. The environment offers a subtle, spatial engagement not with feminist discourse, girlhood, or womanhood, but with femininity itself: the material residue of tastes, styles, and their attendant hues that modernity has projected onto people labeled female. Much second-wave feminist literature aims to liberate the female body …

June 29, 2020 – Feature

London Roundup

Ben Eastham

Every time I approach White Cube’s gleaming south London base, I am reminded of a trope in science-fiction films: a professor of linguistics is whisked to a top-secret government facility, decontaminated, and introduced to an alien intelligence whose ominous burps she is tasked with translating. These daydreams are no doubt prompted in part by mental association with Brian O’Doherty’s Inside the White Cube (1976), which drily observes that the “ideal” contemporary art space “must be sealed off from the outside world” in order to preserve the closed system of values that operates within it. But pulling on a mask, sterilizing one’s hands, and confirming one’s identity with a security guard lends these visions a new lucidity.

Beyond the hermetic seal, Cerith Wyn Evans’s experiments in sculpture and installation are right at home within the self-contained network of relations that O’Doherty describes, with a roomful of smashed glass screens referencing the high-modernist touchstones of Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23) and its documentation by Man Ray. Two potted trees rotating slowly on turntables, their branches splayed over a cruciform bamboo trellis and illuminated by a spotlight that casts their silhouettes over the far wall, suggest an …

March 10, 2020 – Review

Stan Douglas’s “Doppelgänger”

Kevin Brazil

A thread linking Stan Douglas’s work across various media—installation, film, television—is the creation of what he has called “speculative histories.” Take “Scenes from the Blackout” (2017), a series of large photographs on display downstairs at Victoria Miro’s north London outpost. One photograph (Skyline) shows a blacked-out Manhattan skyline; another (Jewels) a hand stealing diamonds. Elaborately staged, lit with spotlights, and shot from high angles as if by a movie camera, this alternative history of a New York power cut is produced by manipulating the formal artifice of photography as a medium.

This same impulse has produced the main work in the show, the film installation Doppelgänger, which premiered at the Venice Biennale in 2019 and which is projected onto two square screens hanging side by side from the upstairs gallery’s ceiling (in another of its many doublings, it was also exhibited concurrently at David Zwirner, New York until February 22). Doppelgänger is set in an alternative recent past with futuristic yet analogue technology, where typewritten messages are transmitted in metal boxes. One screen tells the story of an astronaut called Alice (call her Alice-1) who is simultaneously cloned and teleported to a spaceship in another galaxy. Her race is …

March 4, 2020 – Review

“Contagio”

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

The logic of contagion rests on an “us vs them” binary—healthy/sick, in/out, loved/feared—and this exhibition of nine mostly UK-based Latin American artists has the feeling of a diverse group banding together for support. Instigated and curated by the Venezuelan painter Jaime Gili, it foregrounds the importance of collegiality and self-organization in an increasingly hostile environment.

The show tackles pressing political questions with a looseness and lightness of touch characterized by subtle metaphors rather than on-the-nose statements (the exception is a billboard-sized map at the entrance to the gallery, which shows the proliferation of legal and illegal mines across the Amazon basin). In Martín Cordiano’s Host (2020), a tall reading lamp pierces through a mid-century sideboard, on one corner of which a massive sphere of plaster bulges like a tumor. The result is witty, oddly beautiful, and violent. The exhibition text identifies Jacques Derrida’s writing on hospitality as an influence on Cordiano, who seems here to be giving form to the anxieties generated by the a guest’s fragile relationship to their host: a figure who ostensibly extends care while constantly policing the boundaries of the offer of hospitality.

Resting on a nearby plinth is an oversized bronze cast of a …

January 29, 2020 – Review

Bruce Conner’s “BREAKAWAY”

Jeremy Millar

The work of the American artist Bruce Conner—dime-store assemblagist, quick-splice cineaste—is too little seen in the UK, and so we should be grateful to Thomas Dane Gallery for their recent periodic exhibitions of his work, each focused on a single film. Following CROSSROADS (1976) in 2015 and A MOVIE (1958) in 2017 comes BREAKAWAY (1966): three films from three different decades. Their achronological presentation seems appropriate, given Conner’s fascination with the temporal shifts which film afforded him.

While BREAKAWAY shares some of the concerns of these other films—such as the destructive impulses of desire and the emptiness that lies at the center of things—it is in many respects the simplest of the three. It is also the only one made from footage Conner shot himself, rather than material found from other sources. The location was a collector’s house in Santa Monica. Conner’s friends, the actors Dean Stockwell and Dennis Hopper, held the lights, and the subject was Antonia Christina Basilotta, a young singer and choreographer whom Conner had met through Stockwell and artist Wallace Berman. The five-minute film opens with a flickering image of Basilotta posing against a black background, dressed only in a black bra and black tights …

January 7, 2020 – Review

Valie Export’s “The 1980 Venice Biennale Works”

Orit Gat

The two acts for which VALIE EXPORT is most famous are naming herself off a pack of cigarettes and a performance that involved wearing a pair of trousers with the crotch cut out, exposing her vulva. The Austrian artist, so associated with this bold punk aesthetic, represented her nation at the Venice Biennale in 1980, a rare occasion of recognition for a woman artist at the height of her career rather than its tail end, coming at the peak of her most prolific decade. Collecting these pieces together again, almost 40 years after they were shown at the Austrian Pavilion, makes clear how over time, the shock element of EXPORT’s art has faded, yet what remains is an always-pertinent critique.

EXPORT’s work is a reflection on the place women are afforded—that is, must fight for—in the communities in which they live. On view is “Body Configurations” (1972–76), a series of black-and-white photographs that show EXPORT adjusting her body to the city—lying with her back arched to match a curve in the pavement in ABRUNDUNG I [Rounding I] or sitting against the corner of a building, her hands stretched to touch its two sides in VERFÜGUNG I [Available I] (both works …

November 27, 2019 – Review

Ignacio Acosta’s “Tales from the Crust”

Tom Jeffreys

What do the gray-white, snow-laden forests of Scandinavia have in common with the dry red sands of the Atacama Desert in Chile? Both, in the words of Silvia Federici, are “sacrifice zones” of capitalism: places that contain riches extracted by multinational mining corporations with little care to the destruction they cause—to water, soil, air; to human and nonhuman communities.

Ignacio Acosta’s “Tales from the Crust” connects these places in a solo exhibition divided quite neatly into three parts. Covering the gallery’s street-level windows and visible to passers-by are three large-scale photographs of landscapes that have been radically altered by mining: a looming slag heap, a drone shot of a distance marker, and a eucalyptus forest planted to absorb contaminated water. To the right as you enter the gallery is a room of archival materials, filmed interviews, documents, photographs, and rock samples, presented on and around a freestanding metal structure. Here, Acosta not only makes visible his own research process but also acknowledges that struggles against multinational companies are diverse, collective, and ongoing: there are many tales from the crust.

One focus in this room is the corporate group Antofagasta PLC in Chile: a video interview with researcher Patricio Bustamante reveals the …

November 12, 2019 – Review

Danh Vo’s “untitled” and “Cathedral Block, Prayer Stage, Gun Stock”

Harry Thorne

We create our own artworks. Regardless of their maker or mark, we push ourselves through the objects and images that deign to confront us and, as such, shape ourselves and our newfound companions into something other than we were before. It could be said that when we interact with art objects, we actively collaborate with another, with one another, which is a pleasant way of narrativizing our lowly passage through life: we work alongside the many things of the world so as to generate meaning.

This notion of incorporeal co-existence would suggest that the self is an entity less fixed and singular than it is multivalent, multiplicitous, more. The memory of Édouard Glissant floats, preaching the oft-quoted pledge “not to be a single being”; Antonio Gramsci, cited prominently in Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978), writes of “‘knowing thyself’ as a product of the historical process to date, which has deposited in you an infinity of traces.” Self as infinity. Infinity as self.

Vietnam-born Danish artist Danh Vo speaks in similar tones: “I don’t really believe in my own story, not as a singular thing anyway. […] I see myself, like any other person, as a container.” But are we containers or conduits? Do …

October 17, 2019 – Review

Moyra Davey’s “i confess”

Brian Dillon

Each time Moyra Davey speaks in her new film i confess (2019)—spinning a narrative that’s at once autobiographical, political, essayistic—she’s preceded briefly by a faint ghost-voice, anticipatory echo. It’s the sound of the artist’s own voice, prerecorded and playing off her iPhone as in-ear prompt, while she paces her New York studio, repeating the script aloud. Davey has used this subtly deranging method before, in films such as Les Goddesses (2011) and Hemlock Forest (2016). It gives her a halting, spacey presence on screen, as though she’s merely the conduit for personal memory, cultural-political reflections and a shelf’s-worth of citation. In the past, Davey’s films have invoked Anne Sexton, Mary Wollstonecraft, Chantal Akerman, and Derek Jarman. When we first see and hear her in i confess, which is shown alongside a series of photo-etchings, she’s thinking about James Baldwin—a famous 1965 debate with William F. Buckley Jr. plays on YouTube in the background—and about the vexed history of French-Canadian identity.

Davey was born in Toronto in 1958, and grew up in Montreal, where she felt ashamed to be an anglophone outsider, and at the same time terrified of the strictures of Québec Catholicism. Early in i confess she tells us …

October 7, 2019 – Feature

London Roundup

Chris Fite-Wassilak

%20provisioning_hr.jpg,1600)

The world is burning. This is not a metaphor. The sky is bleached a searing lime green, tinged with burned orange that reflects off relentless choppy waves. Suddenly, the sky goes blood red and the horizon blackens, the sun a dull hole punched in the sky. Our view shifts, panning quickly to the left, then back again, as if searching for something, anything. The sky then changes again to a blinding sherbet yellow. The screen depicting this scene, mounted on a metal rack above a whirring circuit board, gives us a certain vision of our current reality. The shifting colors are a translation of information from a small atmospheric monitor mounted on the back of the rack. It’s not clear what directly causes the hues to brighten or waves to get that bit higher or more intense in Yuri Pattison’s sun[set] provisioning (2019) at mother’s tankstation—whether the car exhaust from the street outside, or the hungover breath from bodies in the room might make the scene that bit more trippy. The contraption offers a heavily mediated fiction, but it also makes an actuality visible and present: a drowned world, made hallucinatory and beautiful by toxins that saturate the air and …

September 11, 2019 – Review

Mike Nelson’s “The Asset Strippers”

Jeremy Millar

The relationship of sculpture to industry and its processes is a long one, and heroic—think of all those bronze figures emerging from armory foundries, of Marcel Duchamp and Constantin Brancusi wandering jealously through the 1912 Paris Aviation Show, of Richard Serra rolling steel at a Baltimore shipyard—but seldom is it elegiac. Such a description would however be fitting for The Asset Strippers (2019), an extraordinary installation of sculptures by Mike Nelson. The work has been assembled from machinery and industrial materials and fixtures bought from auctions disposing of the assets of UK factories, although Nelson does not simply turn the expanse of Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries into a storehouse, but rather places them in new configurations. Despite the technical difficulties of moving these massive objects—their total weight is estimated to be approximately 40–50 tons, close to the loading capacity of the gallery floor—Nelson’s touch is assuredly light. Often little more is done than stacking objects on top of each other—a cement mixer is placed high upon two wooden work benches, its drum upturned as if yearning to peer even higher—but the effect is transformative. One begins to see them not only for what they once were, but for what else …

July 29, 2019 – Feature

“Misbehaving Bodies: Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery”

Philomena Epps

“Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship in the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick,” wrote Susan Sontag in Illness as Metaphor (1978), “although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.” This quote opens “Misbehaving Bodies” at the Wellcome Collection, which places Jo Spence’s healthcare work from the 1980s in conversation with Oreet Ashery’s 12-part web series “Revisiting Genesis” (2016). Through references to chronic and fatal illness, identity formation, medical discourse, and the politics of healthcare, the exhibition pays particular attention to how citizenship to the “kingdom of the sick” might productively disrupt and diversify common understandings of life and death, the body, and community.

Spence’s autobiographical artwork Beyond the Family Album (1979) takes the conventional form of the family photo album—photographs and press clippings are affixed to large sheets of paper, accompanied by captions and extended passages of text—but subverts the form by manifesting as a counter-archive of the self. By charting her divorce, her parents’ ill health, and her own struggles with chronic asthma, in addition to interrogating the invisibility …

July 23, 2019 – Review

“Food: Bigger than the Plate”

Chris Fite-Wassilak

Welcome to a review of the latest blockbuster exhibition at the world’s largest museum of decorative and applied arts, focusing on the simple matter of food. As a precise, expansive look into the future of food, the exhibition includes a smorgasbord of over 70 artists, designers, and producers. I’ll be giving you a tasting menu.

To start, the appetizer is an assortment of the types of descriptions and phrases we use to talk about food, seasoned heavily with useless generalizations and limp truisms: we all eat; food connects us; food is more than just food; and so on. Such language dots the exhibition, presented on a bed of colorful, hyper-designed alcoves and panels, as we are led on a sumptuous journey through sections titled “Composting,” “Farming,” “Trading,” and “Eating.”

Our main courses are presented as a series of altars, spot-lit objects placed on pedestals, most often accompanied by a video of the people who made what sits in front of us, and some context as to why they made it. The first course is a pair of plastic toilets sitting side by side. We are apparently not intended to use them, but instead appreciate the plastic bag that lines the bowl. Loowatt’s …

July 10, 2019 – Review

“The Enigma of the Hour: 100 Years of Psychoanalytic Thought”

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

Psychoanalytical theory might have fallen out of favor in the visual arts, but the fields still share a number of core concerns. Both create conditions in which the unconscious can materialize through processes of language, translation, metaphor, and interpretation. With these common terrains as a starting point, Dana Birksted-Breen, editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis (IJP), commemorates the journal’s centenary in an exhibition at London’s Freud Museum which comprises two overlapping threads. One maps the origins of the publication in a thoroughly researched cabinet display containing letters, photographs, paintings, and archaeological artifacts, including Egyptian sphinxes and Etruscan mirrors from Sigmund Freud’s collection. The research pays close attention to the role that women—most notably Joan Riviere, Marjorie Brierley, Anna Freud, and Alix Strachey—played in the development of the IJP. The materials also evidence a fascinating link to the Bloomsbury Group via two of its one-time editors: James Starchey, who with wife Alix translated Freud into English, and and his successor Adrian Stephen, Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell’s younger brother. Both psychoanalysts are present via letters and issues of the journal and by two stunning portraits painted by Duncan Grant.

The exhibition’s second thread is curated by Simon Moretti and Goshka …

April 10, 2019 – Review

Sophia Al-Maria’s “BCE”

Philomena Epps

Sophia Al-Maria’s exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery—in which two films are separated by a thick PVC industrial strip curtain, one screened in a room painted black, the other white, one rooted in the future, the other the past—is the culmination of her position as the gallery’s writer in residence. Over the last year, the artist organized a series of associated events (intended specifically for women and non-binary guests) that correspond with the rhapsodic narrative texts written for the Whitechapel website: “We Share the Same Tears,” “We Swing Out Over the Earth,” and “We Ride and Die With You.”

Al-Maria was inspired by Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1986 essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” which posed an alterative, non-linear, feminist form of storytelling realized through speculative fiction. In the essay, Le Guin writes that the first useful tool for humans is a carrier bag for food—“a leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container”—rather than the “sticks and spears and swords” of masculine domination. For her, the carrier bag becomes a metaphor for the telling of multiple stories that resists the narrative of the “bashing, thrusting, raping, killing” …

March 27, 2019 – Review

Beatrice Gibson’s “Crone Music”

Jeremy Millar

In her 1988 essay “The Fisherman’s Daughter,” Ursula K. Le Guin reflects on how women writers have long supported one another: “there is a heroic aspect to the practice of art; it is lonely, risky, merciless work, and every artist needs some kind of moral support or sense of solidarity and validation.” In content and form—a loosely assembled collage in which the author is placed in a position of kinship with her readers and those writers who came before—the essay shares much with “Crone Music,” an exhibition by Beatrice Gibson of two new films which are complemented by a program of screenings, rehearsals, readings, and performances by many writers, artists, and musicians who Gibson collaborated with for her films.

While Gibson’s work has long been made in relation to the work of others, these have usually been major male figures—William Gaddis, for example, or Cornelius Cardew—in these new films, the references are to more marginalized figures, notably women, queer communities, and poets. The exhibition’s title is borrowed from the 1990 album by Pauline Oliveros. Deux Soeurs Qui Ne Sont Pas Soeurs [Two Sisters Who Are Not Sisters] (2019) takes its title from a film script written in 1929 by Gertrude Stein, …

March 14, 2019 – Review

Linder’s “Ever Standing Apart From Everything”

Chris Fite-Wassilak

Let’s put it all up front: this exhibition is made up of 73 small collages, created between 2007 and 2019, each featuring one or two human bodies, accumulatively displaying 23 nipples (four of which have a more apparently male owner), four pudenda, and one (erect) penis. Some of these people lounge about in bygone versions of tastefully decorated interiors, looking confidently into the middle distance; a few in a state of semi-undress contort into various suggestive poses, giving the camera a dead-eyed stare; most of them, though, are preoccupied with the furniture and silverware being shoved into various orifices. In The Model 5 (2015), one woman looks on while another has a set of black enamel drawers angled between her legs, while in Magnitudes of Performance III (2012), a man looks ready to introduce an old hi-fi amplifier to his supine male partner. Most of the imagery for these collages seems to come, to start with, from porn magazines, and the rest from home décor catalogues. The excerpts from the latter—sofas, vases, and one well-placed tiger-striped lounge chair—act like a form of comedy censorship, blocking out the revelations and penetrations of the former to give the new images a more …

March 7, 2019 – Review

“We are the people. Who are you?”

Izabella Scott

Farley Aguilar’s cartoonish Bat Boy (2018) is hanging in the first room of “We are the people. Who are you?” at Edel Assanti, an unsettling group show featuring 11 artists that examines mass-media and the rise of populism. As the painting’s title suggests, it depicts Bat Boy, a fiendish mutant with huge eyes and sharp teeth popularized in the early 1990s by the American tabloid Weekly World News. Here, this devilish man with pointed ears is depicted reading the Weekly World News on his porch. He casts a blood-red shadow; the headline reads, “KILL BAT BOY.” Morphing subject and reader, Aguilar points to the danger of becoming the very media one consumes.

Bringing together artists from different political climates such as Ukraine, Nicaragua, and Turkey across drawing, sound, video, sculpture, and installation, “We are the people” embraces scope rather than focus. The curatorial breadth allows for illuminating juxtapositions to emerge between pairs or clusters of artworks. On the wall near Bat Boy is Jamal Cyrus’s triptych Kennedy King Kennedy (2015): laser-cut reproductions of front pages from the Chicago Daily Defender announcing the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and Robert F. Kennedy.

This juxtaposition is echoed in the present political …

January 25, 2019 – Review

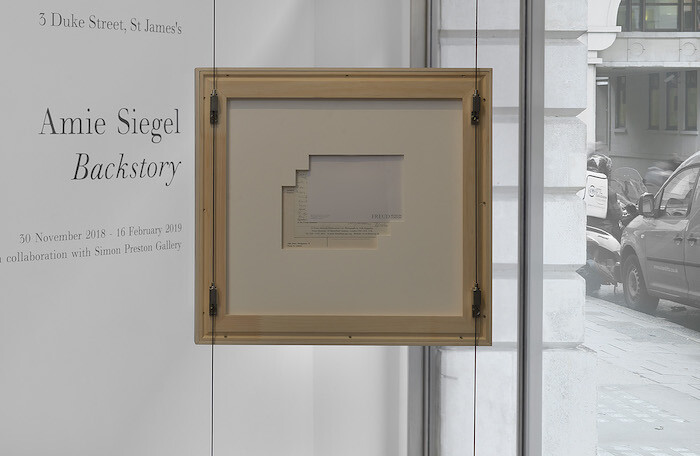

Amie Siegel’s “Backstory”

Filipa Ramos

Continuously reappearing throughout the French version of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film Le Mépris [Contempt], Georges Delerue’s melody Thème de Camille is the epitome of contained tragedy. Composed for a string orchestra, it has a regular, continuous motif traversed by arpeggios in counterpoint. This combination creates an immensely pleasurable (and sad) tune that flows back and forth, like the player’s hand bowing across the cello’s strings; like the calm Mediterranean summer sea waves that surround the Casa Malaparte in Capri, in which the central moments of Le Mépris take place; and like Amie Siegel’s elegant and sharp exhibition “Backstory,” whose interplay of absences and presences pay tribute to a fundamental knot of twentieth-century Western film culture.

“Backstory” honors its title. Through a set of paper works, “Body Scripts” (2015), and two video installations (Genealogies, 2016, and The Noon Complex, 2016), the exhibition gravitates around Godard’s stunning depiction of the collapse of a marriage between a submissive screenwriter (Michel Piccoli) and his loveless wife (Brigitte Bardot). Remaining close to Siegel’s ongoing inquiry into how value is achieved and generated and her interest in the meta-reflexivity of cultural production, the show brings forward a set of literary, cinematic, and pop-culture references that contextualize and …

December 19, 2018 – Review

Pierre Huyghe’s “UUmwelt”

Flora Katz

Five large, freestanding LED panels fill the spaces of the Serpentine. Despite their technological nature, they look like temporary plaster walls and give the rooms a stripped appearance. Images scroll onscreen at high speed. In the darkened exhibition space, they have peculiar light and colors, cold and clear tones. Sounds can be heard, but like the shapes on the panels, I don’t know what they relate to: A microphone? A bird? Nothing corresponds to anything entirely; the sounds oscillate between machine, human, and animal. The same is true of the strange scent diffused in the air. Dust clings to viewers’ shoes. It will spread to the gardens, the streets, the tube. It comes from a large mural on the wall of the main room, a version of timekeeper (1999). Timekeeper is an archeology of the place, a mural that looks like the impression of the rings on a tree trunk, made by sanding down the wall of the exhibition space, each layer of exposed paint forming a different color circle. Here, the same sanding process is at play but it forms sinuous lines, like a map of an unknown territory. Flies roam overhead. They were born in the gallery’s ceiling, …

November 28, 2018 – Review

Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s “Earwitness Theatre”

Jeremy Millar

Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s latest project emerged from his involvement with an extensive—and emotionally harrowing—2016 investigation by Forensic Architecture into Saydnaya Prison in Syria, commissioned by Amnesty International. (The investigation was presented in Forensic Architecture’s exhibition at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts earlier this year, for which they were nominated for the Turner Prize.) Given the lack of images of Saydnaya, and that prisoners were often kept in darkness or blindfolded, the investigation made use of the inmates’ memories of sounds heard within the prison, sensory experiences made all the more acute given the silence that was brutally enforced. Although the work became one of Amnesty’s biggest campaigns of recent years, and arguably helped to shift perception of the Syrian regime in the West, much of the testimony gathered was of little use in court, although it was not without meaning; such might broadly be considered the status of art, and it was within the space of art that Abu Hamdan found somewhere for that which was previously inadmissible.

As with Abu Hamdan’s earlier video Rubber Coated Steel (2016), in which the artist analyzed audio recordings of a 2014 protest in the occupied West Bank to ascertain whether live rounds or rubber …

October 12, 2018 – Feature

London Roundup

Mariana Cánepa Luna

Just as Frieze Art Fair opened last Wednesday, Prime Minister Theresa May gave her keynote speech—and dared to dance again—at the Conservative Party Conference in Birmingham. She announced that freedom of movement would be terminated “once and for all” by limiting access to “highly skilled workers” (in short, migrants earning over 30,000 British pounds per year). Countless art professionals earn much less (including entry-level curatorial staff at Tate, and yours truly), as well as doubtless many of the myriad gallery and museum folks involved in the city-wide jamboree of Frieze week. How do we imagine London’s contemporary art ecology post-Brexit, a scene that has grown exponentially since Tate Modern’s opening in 2000 and the first Frieze Art Fair in 2003? The question of how the 2019 edition of the fair is going to be affected was the elephant in the tent. Most people I asked shrugged: negotiations are still ongoing, consequences are yet to be seen. “It’ll be fiiiiine,” a London museum director told me. “Maybe we’ll visit a smaller fair, like the first editions—remember those days?” opined a British gallerist friend working in New York. Although one could put this upbeat denial down to the cliché of dark British …

September 28, 2018 – Review

Mika Rottenberg

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

Shucking oysters, turning wheels and levers, sitting in a rammed plastic warehouse while staring at a mobile phone—to enter Mika Rottenberg’s universe is to fall down a rabbit hole of stoic drudgery. The worlds the artist conjures in her video installations are populated by extraordinary characters, such as the fantasy wrestlers who pulverize red fingernails into maraschino cherries in the artist’s MFA degree show piece Mary’s Cherries (2004), or the women who produce cultured pearls by turning cranks to power fans which inflate cartoonish noses in NoNoseKnows (2015). They are all committed to odd tasks with resigned zeal, as if there was no escape to their abstruse internal logic. Rottenberg’s works offer piercing critiques of the absurd conditions of labor under neoliberalism: the precariousness of the gig economy has turned millions into impoverished workaholics, and while AI and automation are threatening countless jobs across the globe, presenteeism still reigns supreme in most cubicles and departments. The aroma of lives wasted on futile endeavors might dominate here, but instead of opting for kitchen sink tragedy, Rottenberg plunges into Technicolor farce: grotesque reflections on unhinged times.

Goldsmiths’s new Center for Contemporary Art (CCA), run by curator Sarah McCrory, is opening its doors with …

July 18, 2018 – Feature

“Signals: If You Like I Shall Grow”

Isobel Harbison

“Signals: If You Like I Shall Grow” is an exhibition of works that come from a past that was alive to the future. Initiated by Mexico City’s kurimanzutto, held across the two spaces of London’s Thomas Dane gallery, and curated by Isobel Whitelegg, the exhibition echoes the interdisciplinary alliances of its subject matter: London gallery Signals’ activity between 1964 and 1966. As well as being a commercial entity, Signals was also an innovative project space, an experimental publishing endeavor, and a loosely associated set of artists primarily active between the UK (London and various regional centers) and Latin America (Venezuela and Brazil, primarily).

Both moderately sized spaces are dense with works, 42 in each. But an absence of durational work (with the exception of Gustav Metzger: Auto Destructive Art, by Harold Liversidge [1965] and Free Radicals by Len Lye [1958–79], shown consecutively on a monitor, on loop) and the careful editing of archive material (there’s a vitrine of editions near the entrance and, further into the gallery, a bench/table structure featuring excerpts from several publications), means that navigating through it is not an overwhelming documentation-heavy endeavor. There are no wall labels; the works are not divided by medium, geographical origin, theme, …

July 3, 2018 – Review

Joan Jonas

Philomena Epps

When I was a child, I received a disco ball as a birthday gift. Hung haphazardly above my bed and lit by a repurposed old desk lamp, it reflected a scintillating constellation across the ceiling. In a flick of a switch, the quotidian transformed: I had entered a secret world. A kind of Proustian magic occurs when an artwork triggers not only an involuntary memory but an ineffable bodily feeling. Walking into Joan Jonas’s installations—Reanimation (2010/2012/2013) and Wind (1968)—in the East Tanks of Tate Modern did precisely that. The cavernous space had become an enigmatic new universe: the rough walls animated by shimmering video projections, with crystal spheres refracting flickering light, and the howling noise of gale-force wind intertwining with strange percussive sounds.

Jonas’s oeuvre eludes genre. Throughout her career, she has blended technology—video screens, re-recorded backdrops, overheard projectors—into historical systems of communication, engaging with traditions of shadow puppetry, mythology, ritualistic music, and Noh theatre. Her work travels from factory lofts to wasteland docks, across landscapes and seascapes, deserts, cities, and hilltops. Jonas’s show at Tate Modern eschews a chronological retrospective in favor of a nonlinear survey paired with live performance and cinema programs. In alignment with Aby Warburg’s logic of …

June 13, 2018 – Review

Abigail Reynolds’s “The Universal Now and further episodes”

Tom Jeffreys

“Many artists consider books and libraries to be oppressive hierarchies of knowledge, dogmatic and hectoring,” writes artist Abigail Reynolds in her new book Lost Libraries. But Reynolds does not agree: “I consider them the gates of freedom.” Three simultaneous exhibitions in east London exemplify this fascination with books and their material relationship to time and knowledge: a display of artist books at bookartbookshop, an artists’ bookshop; a retrospective including collaged book pages at PEER gallery; and a new film work, Lost Libraries (2018), showing on two television screens among the books and computers of Shoreditch Library.

Both book and film versions of Lost Libraries are the result of a journey undertaken by Reynolds between 2016 and 2017. Given financial and logistical support as the third recipient of the BMW Art Journey, a project by BMW and Art Basel that commissions artists to visit foreign locations and create new work, Reynolds travelled by plane and motorbike along the Silk Road from Xi’an, China, to Rome, Italy, visiting the sites of 15 libraries lost or destroyed over the past 2000 years. In Nishapur, Iran, she went to an empty field where a library once stood. In a museum in Xi’an, the characters of …

June 1, 2018 – Review

Ed Atkins’s “Olde Food”

Patrick Langley

A boy in a bruise-pink jacket jogs through a dusky idyll, limp-kneed and panting for breath. The grass that flanks the path is dappled with blooming flowers: purple, yellow, orange, and white. In the foreground is an upright piano, incongruously plonked between two trees. The boy staggers past it and out of sight. Seconds later, he’s back where he started. He falters past the piano, vanishes, and rematerializes in an endless, purgatorial circuit. He looks exhausted. Watching this digital animation, I begin to feel exhausted too. Is he being punished, condemned to enact a pitiless ritual? If so, for what purpose?

Across from Good Wine (the animations all date from 2017, the year they were shown at Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau), and past a pair of monumental steel clothes rails hung with a spectacular array of old opera costumes acquired from the archives of the Deutsche Oper Berlin (Masses 1 and 2, 2018), a salvaged door is mounted to the wall (Untitled, 2017). Its darkly varnished surface is laser-etched with a cryptic text: one of several such works (all untitled) co-written by Atkins and whoever’s behind the acerbic, anonymous blog Contemporary Art Writing Daily. Some offer arch commentaries on the exhibition (“Old food …

May 18, 2018 – Review

Yto Barrada’s "Agadir"

Mitch Speed

Just before midnight on February 29, 1960, an earthquake hit the Moroccan city of Agadir, killing between 12,000 and 15,000 people—roughly a third of the city’s population. As many were injured; at least 35,000 were left homeless. Yto Barrada’s “Agadir,” in The Curve gallery at London’s Barbican Centre, invokes the disaster in oblique and poetic ways across drawings, audio recordings, collage, and film. Despite the breadth of media employed, this is a show that lacks the depth of historical context one might expect from such a weighty subject, compelling viewers to keep reading, watching, and learning after they’ve left the exhibition, in order to fill in the gaps.

Entering the dim gallery was exciting. Its dark lighting and dramatic colors—the long curving wall painted black, the carpet beneath it blood red—recalled the set of a camp Italian horror film. (The cinematic influence is in keeping with the artist’s broader practice: in 2006, Barrada founded the Cinémathèque de Tanger, an independent project that, operating from Tangier’s Cinema Rif, is dedicated to the local and international promotion of independent Moroccan film.) On the Barbican’s curving wall are sixteen large drawings, “Untitled (Agadir)” (2018), executed by scratching broad white lines from the black paint. …

April 20, 2018 – Review

“Counter Investigations: Forensic Architecture”

Naomi Pearce

In his 2014 lecture “The Future of Forensic Science in Criminal Trials,” judge Thomas of Cwmgiedd, Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, identified a communication problem. In light of the increasingly complex science used in court, he called for a set of judicial primers: standardized documents, written in “plain English,” to relay core scientific principles to lawyer, judge, and jury. Contrary to narratives propagated by popular crime dramas, he argued: “however eminent and reliable the expert, the presentation of forensic evidence is rarely black and white.”

The slippery, kaleidoscopic status of evidence feels like the point and not the problem in “Counter Investigations,” a survey of work by Forensic Architecture, a research collective of academics, investigative journalists, and creative practitioners including architects, programmers, and filmmakers. Slickly installed across the Institute of Contemporary Art’s two floors, a series of multi-disciplinary investigations into human rights abuses and armed conflict unfold across video installations, models, and wall graphics. Described by Forensic Architecture founder Eyal Weizman as “the archaeology of the very recent past,” the group use forensic methods to map and reconstruct sites, such as the Saydnaya Prison in Syria, or events, such as Israeli military operations in Rafah, Gaza, in August 2014.

The …

March 29, 2018 – Review

"Women Look at Women"

Lucy Reynolds

I almost walk past the entrance to “Women Look at Women,” the inaugural exhibition at Richard Saltoun’s new space on London’s New Bond Street, delayed and disorientated by the glossy rows of designer shops and galleries that surround it. Catherine—a friend on a break from the picket line where she, like many UK university lecturers, is fighting to keep her pension rights—is already there, taking succor from women’s images of themselves and each other. “I was just looking at this,” she says, pointing to Marie Yates’s photographic installation The Missing Woman (1982–84). Catherine’s gesture encompasses a wall of irregularly spaced photomontages: a mixture of grainy, hand-tinted images, polaroids, photocopies, and text rendered in Courier typeface and neat handwriting. One image—a color photograph of a telephone receiver and a telegram overlaying that of a roadside in blurred black and white—is accompanied by the line “Somewhere there is a point of certainty.” It holds out an unattainable promise of clarity in the game of decipherment and elusive autobiographical disclosure which Yates’s images put into play.

The Missing Woman speaks of a time—broadly stretching from the 1960s to the mid-1980s—when women’s images were troubled and interrogated by a newly confident feminist articulation, finding its …

March 21, 2018 – Review

Marvin Gaye Chetwynd’s "Ze & Per"

Philomena Epps