Two parallel world histories are unfolding, with ubiquitous but still disparate points of intersection: the history of geopolitical, environmental, and mental chaos on the one hand, and the history of the automatic order that is extensively concatenating on the other. Will it always be like this, or will a short circuit happen in which chaos takes over the automaton? Or will the automaton rid itself of chaos, eliminating the human agent?

Doomsday Video

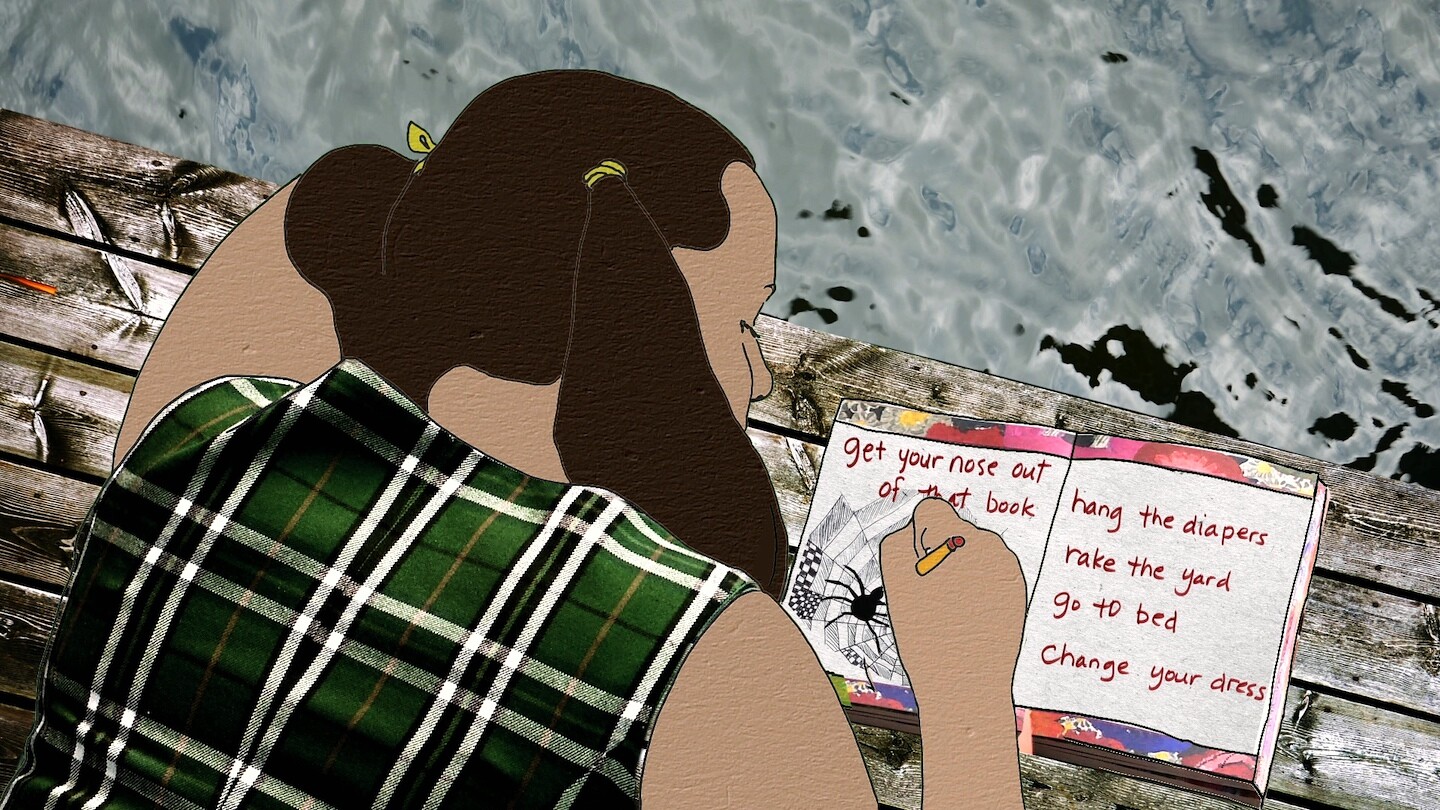

Online discussion with b.h. Yael, Cooper Battersby, and Emily Vey Duke, moderated by Irmgard Emmelhainz

let us investigate the notion of art after the end of the world, and the two figures this proposition conjures up: the figure of the post-, something after the event; and the figure of the main event itself, the end of the world, or if you will, the apocalypse. If there is to be something like art after the apocalypse, this would mean that something is still present, in whatever form, or that something is still being presented and produced, and possibly made public, whether as a form of signification or de-signification. That something (i.e., art) has a meaning or being after the end of the world, whether symbolically or in actuality. Let us first investigate the latter: that the world has in fact ended, but there is still art, still cultural production. By whom is it produced if the world has ended? What could it possibly mean, moreover, to produce art and culture after the end of the world, and thus, presumably, after the end of both the natural and the cultural world, of both bios and zoë, as it were? Would there still be life, or even afterlife, at all? What would it mean to be alive after the end, either as survival or beyond death? Would such a subject still be human, or perhaps rather inhuman or even post-human? In any case, the suggestion of an art after the end of the world implies that there is someone around after the end, whether as producer or receiver: that there is transmission of some sort or another, intentional or unintentional.

If Google Earth or a satellite view of the garbage patch proves to be an impossible undertaking, it is because the plastics suspended in oceans are not a thick choking layer of identifiable objects but more a confetti-type array of suspended plastic bits. Locating the garbage patch is on one level bound up with determining what types of plastic objects collect within it and what effects they have. Yet on another level, locating the garbage patch involves monitoring its shifting distribution and extent in the ocean. The garbage patch is not a fixed or singular object, but a society of objects in process. The composition of the garbage patch consists of plastics interacting across organisms and environments. But it also moves and collects in distinct and changing ways due to ocean currents, which are influenced by weather and climate change, as well as the turning of the earth (in the form of the Coriolis effect) and the wind-influenced direction of waves (in the form of Ekman transport). As an oceanic gyre, the garbage patch moves as a sort of weather system, shifting during El Niño events, and changing with storms and other disturbances. Ocean sensing then requires forms of monitoring that work within these fluid and changeable conditions.

Inaate/se may not be the most obvious example of the science-fictional aesthetics of “Indigenous Futurism,” a term coined by Anashinaabe scholar Grace L. Dillon to describe Native artists who work with science fiction to both refuse the representational expectations of “the Great Aboriginal Story” and play with boundary crossings, claiming the spaces of science, technology, and futurity as their own. Nonetheless, the film employs certain key strategies Dillon finds in such authors, from what she terms “Contact” and “Native Apocalypse” to “Biskaabiiyiang,” an Anishinaabe word “connoting the process of ‘returning to ourselves.’” In so doing, Inaate/se promises an ethics founded on an inhabited futurity, which, no matter how many blows it has suffered, still manages to survive. The Khalils do not attempt to surpass the trauma of erasure; they inhabit and politicize it for a new world to come. In this way, they make the dystopia lived through seven generations a starting point for livelihood.

I’ll put it differently this time: the sovereignty of survivors.

My taxonomy of images of alterity from the twentieth century—ethnographic, militant, and witness—is not opposed but rather transversal to Rancière’s. What I am interested in, firstly, is tracking the kinds of discourses underlying images of Western alterity in the aftermath of the postcolonial critique of the ethnographic image, the demise of the third-worldist militant image, and the exposure of the limitations of the witness image, which often serves to perpetuate the figure of the “victim.” These visibilities have perhaps become the “visual” in Daney’s sense. Second, I wish to consider the possibility of an image of soulèvement—in the sense of an image of an other that could threaten Western imperialism and capitalist absolutism, a system this is consensually driven by the desire and need for visibility, and that legitimates social Darwinism with racism and misogynist speech in the public sphere.

In more than 60 texts, first published on-site at 56th Venice Biennale, artists and writers trace the negative collective that is the subject of contemporary life.