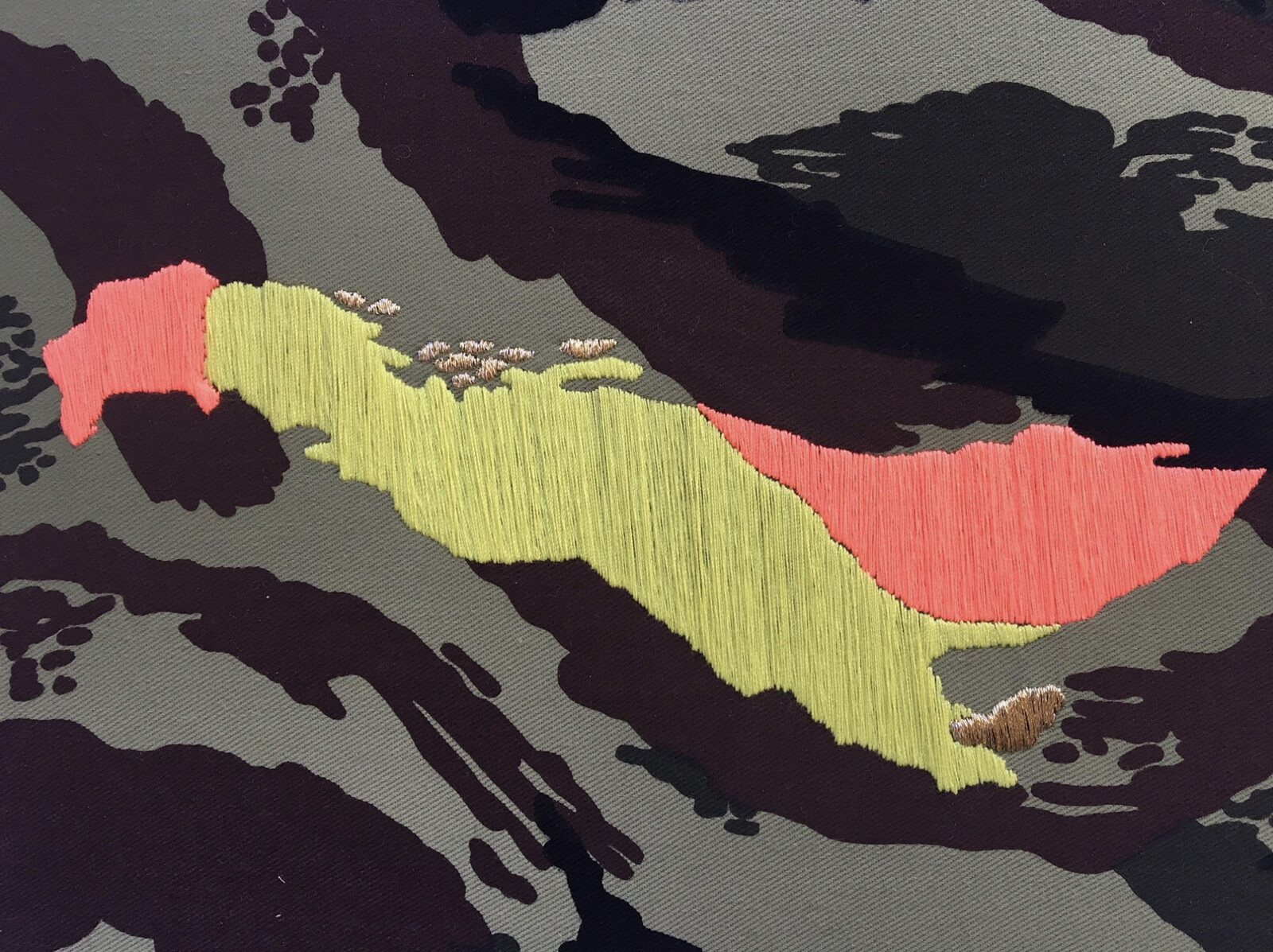

Even though Hija de Perra calls for the recognition of a culturally specific conception of what was called “queer” in Latin America, throughout her work she always remained sharply critical of nation-building perspectives. Indeed, she offered a framework for a hemispheric approach that maintained vigilance against the uncritical implementation of nation-based forms of theoretical and cultural knowledge.

It would be in our collective best interest to abandon old definitions. In the same way that you discovered the truth about Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny, you now discover that there’s been a frame-up—a made-up history, an idealized version of all those things you never wanted to reflect on before and which you adored as if they were gods.

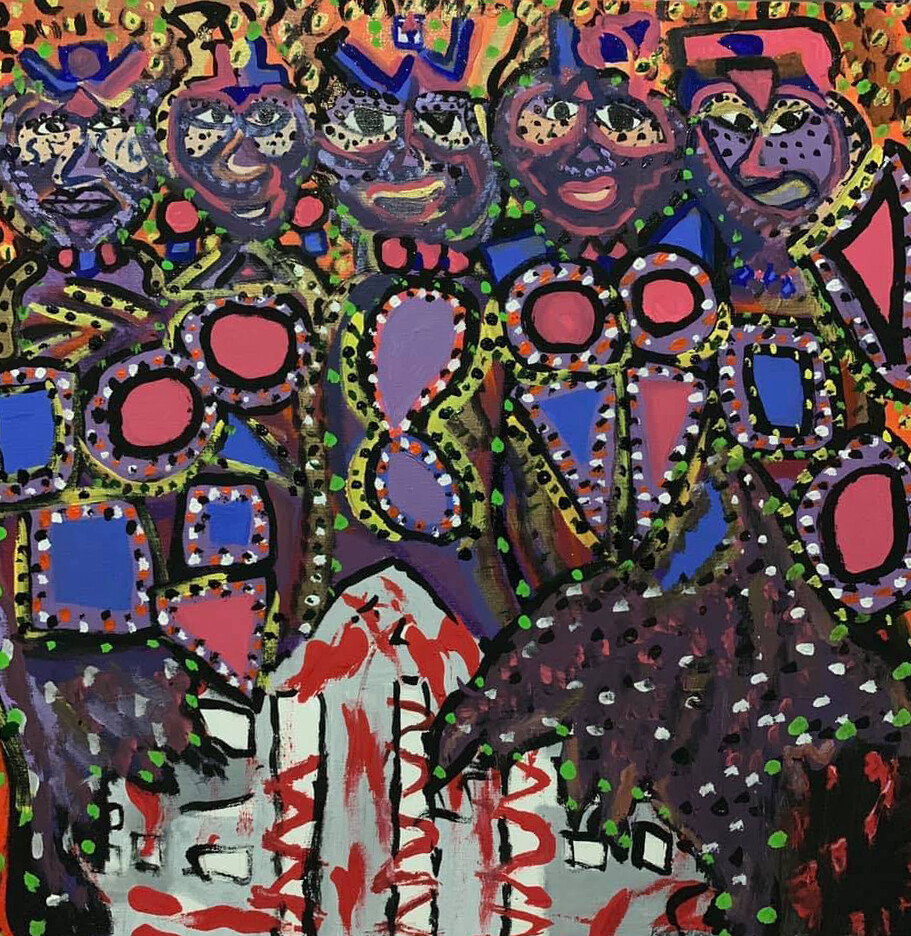

This text might be framed as an offering, an attempt at releasing latent animist lines of possibility for what late twentieth-century works like Bronze Head might do for us in our current climate of rising anti-queer sentiment, on the African continent and elsewhere.

I wish there was a better way to articulate this to you, but life for a Black man is uneasy.

Gender and sexuality are different, and the constant pairing of these issues in public policy sends a confusing message and fails to acknowledge our concrete gendered experiences. White women can create movements and tell stories and not mention Black women and those of color. Gays and lesbians can do the same and boldly practice transphobia. However, when Black women of trans experience speak, we are expected to fight for everyone. That is a Black woman’s narrative.