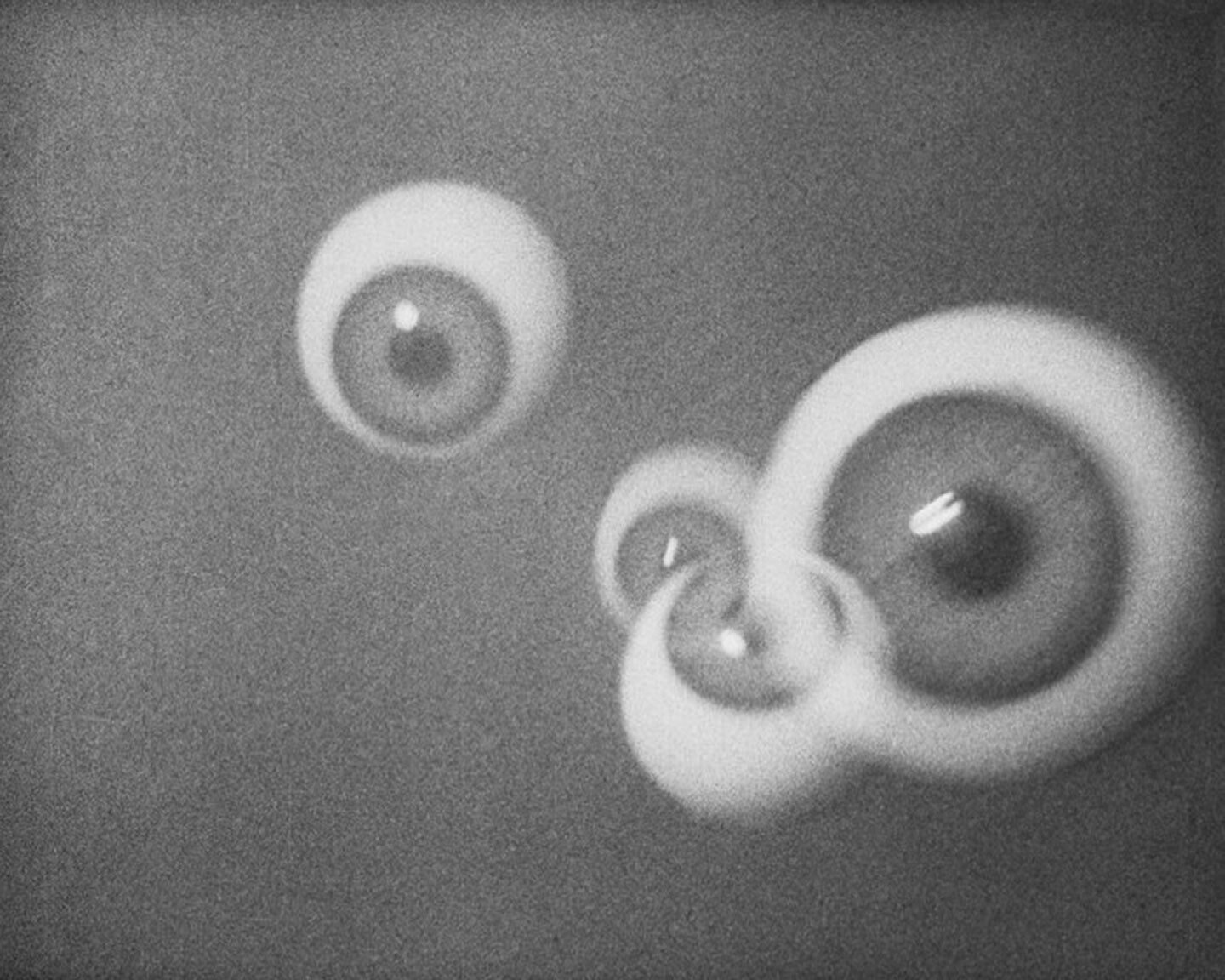

I would say that contemporary civilization is a civilization in which nothingness has disappeared. Kabakov’s treatment of garbage still retains the intuition of nothingness. He assumes that it is possible to disappear into nothingness, and he often describes it—for example, as a departure into outer space from one’s room.

It was only natural that hope for survival was directed towards the museum system. After all, like art objects, humans are only particular material bodies, which can be kept intact and/or repaired and restored if necessary. The State took over the function that had earlier been fulfilled by God and Church. The State was not only responsible for the well-being of the living population but also for its immortality. This care was delegated to the curators.

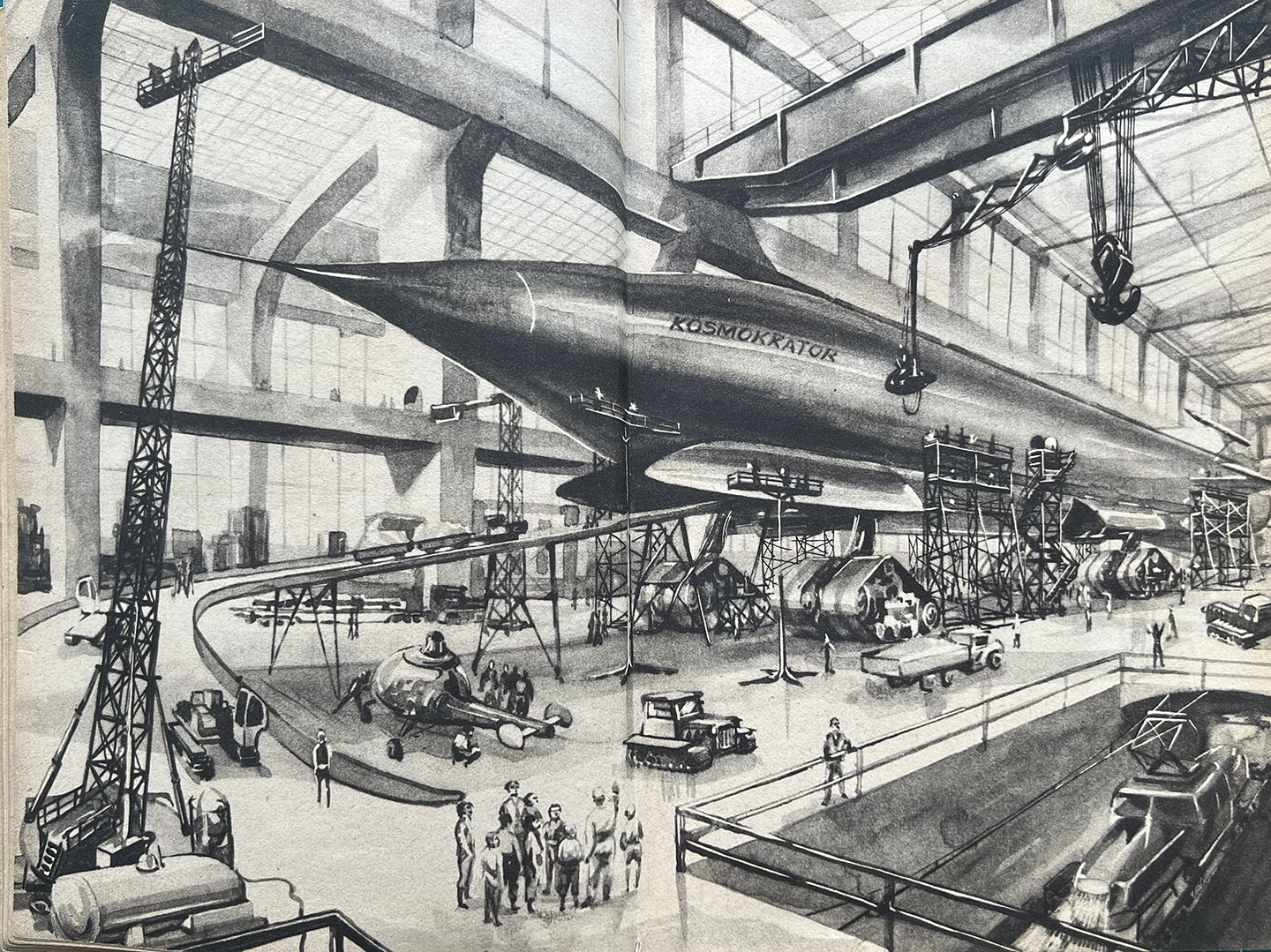

When we speak about cosmic flights and the exploration of space today, we have in mind a dynamic model of technological progress. This dynamic model of progress implies that what we’re doing now in cosmic space will be continued and further improved by the next generation, and so on. The cosmists did not believe in this model. Their questions were along these lines: Why should we be interested in progress if we don’t stand to gain anything from it? If my generation contributes something to cosmic space, how can I benefit from it? I remain mortal, and I remain eternally indentured to progress. I live now—and not in the future. If progress is defined by a dynamic directed towards the future, everyone is yoked to progress, and every generation fast becomes psychologically and physically obsolete.

What do humans do after a successful revolution? The traditional answer is: they become the new masters and begin to impose their will on the losers. Indeed, such is the usual historical dynamic. However, Kojève believed that the working spirit—or rather the spiritualized working body—could be victorious over the animal human body. In other words: he believed that after the proletarian revolution succeeds, proletarians will continue working. But they will not work merely to live or satisfy their desires; they will work to maintain the spiritualized life-form their revolution achieved.

Beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the term “wisdom” appeared very frequently in Soviet philosophy publications. It was used to better situate the doctrine of dialectical materialism within the history of philosophy as well as in relation to science, art, religion, and so on. Dialectical materialism was itself conceived as a form of “wisdom”: that is, as an insight into the whole of the world which was fundamentally lacking in science and art.

No one is asking people in Mali or Peru to live the “Russian way.” This is the difference between today’s Russia and the Soviet Union, because back in those days there were communist organizations and parties in every country of the world. They wanted everyone to live under socialism. It was a universal message aimed at the whole world. But the current “Russian message” is not universal: it is not addressed to the whole world. Second, it makes no sense to anyone. It is incomprehensible even to the Russian people, and even more incomprehensible outside of Russia, because no one understands what this Russian identity is.

The famous historian of Russian philosophy Zenkovsky writes that the entire Sophiological tradition of all-unity was essentially a failed attempt to find a third way between the Christian doctrine of creation on the one hand and pantheism and modern evolutionary theory on the other. The result, in his view, was fantastic, mythical systems, which are full of contradictions and as unacceptable to Orthodox faith as they are to science.

The project of a state based on collective property, thus overcoming the conflict between rich and poor, was formulated and thoroughly substantiated by Plato. Since his time, it has been repeatedly implemented, albeit on a limited scale, primarily in Catholic and Orthodox monasteries, but also in later religious and secular communities. However, the project was realized on the scale of an entire country for the first time by Lenin and his party. Although many regard their implementation of the project as unsuccessful, this view is historically naive. The first experiments of this kind are always short lived. After the French Revolution, democracy survived only a few years, and nearly everyone assumed that it would never be revived. The Soviet regime lasted much longer, and there is no doubt that there will be new attempts to create a classless society based on collective property. Ideas that have a thousand-year history do not vanish without a trace.

The discourse of Marxism, on the contrary, produces not trust but distrust. Marxism is basically a critique of ideology. Marxism looks not for a “reality” to which a particular discourse allegedly refers but to the interests of the speakers who produce this discourse—primarily class interests. Here the main question is not what is said but why it is said.

Even if philosophers are not directly endangered by the existing ideological powers, they are immersed in the everyday life of their society. Thus, to be able to survive in this society they have to accept almost all of its opinions. For example, philosophers have to eat and drink and so they have to accept societal opinions with respect to what is edible and drinkable and what is not. And in the contemporary world, they also have to cross the street on the green light and not the red light, and use their computers in an appropriate way. If philosophers found themselves unable to cope with everyday life and contemporary technology, they would die rather soon. Thus, in order to be consequential, the philosopher has to accept death as a possible and even probable result of the act of epoche. Socrates was ready to accept the death of his empirical self because he believed that a part of his soul remained immortal—and so he could sacrifice his earthly life in the name of eternal life in a society of gods.

In one of his treatises, Malevich writes about the difference between artists and physicians or engineers. If somebody becomes ill, they call a physician to regain their health. And if a machine is broken, an engineer is called to make it function again. But when it comes to artists, they are not interested in improvement and healing: the artist is interested in the image of illness and dysfunction. This does not mean that healing and repair are futile or should not be practiced. It only means that art has a different goal than social engineering.

Before WWII the fascists saw modern art as an ally of communism, communists saw it as an ally of fascism, and the Western democracies saw it as a symbol of personal freedom and artistic realism—as an ally of both fascism and communism. This constellation defined postwar cultural rhetoric. Western art critique saw Soviet art as a version of fascist art, and Soviet critique saw Western modernism as a continuation of fascist art by other means. For both sides, the other was a fascist. And the struggle against this other was a continuation of WWII in the form of a cultural war.

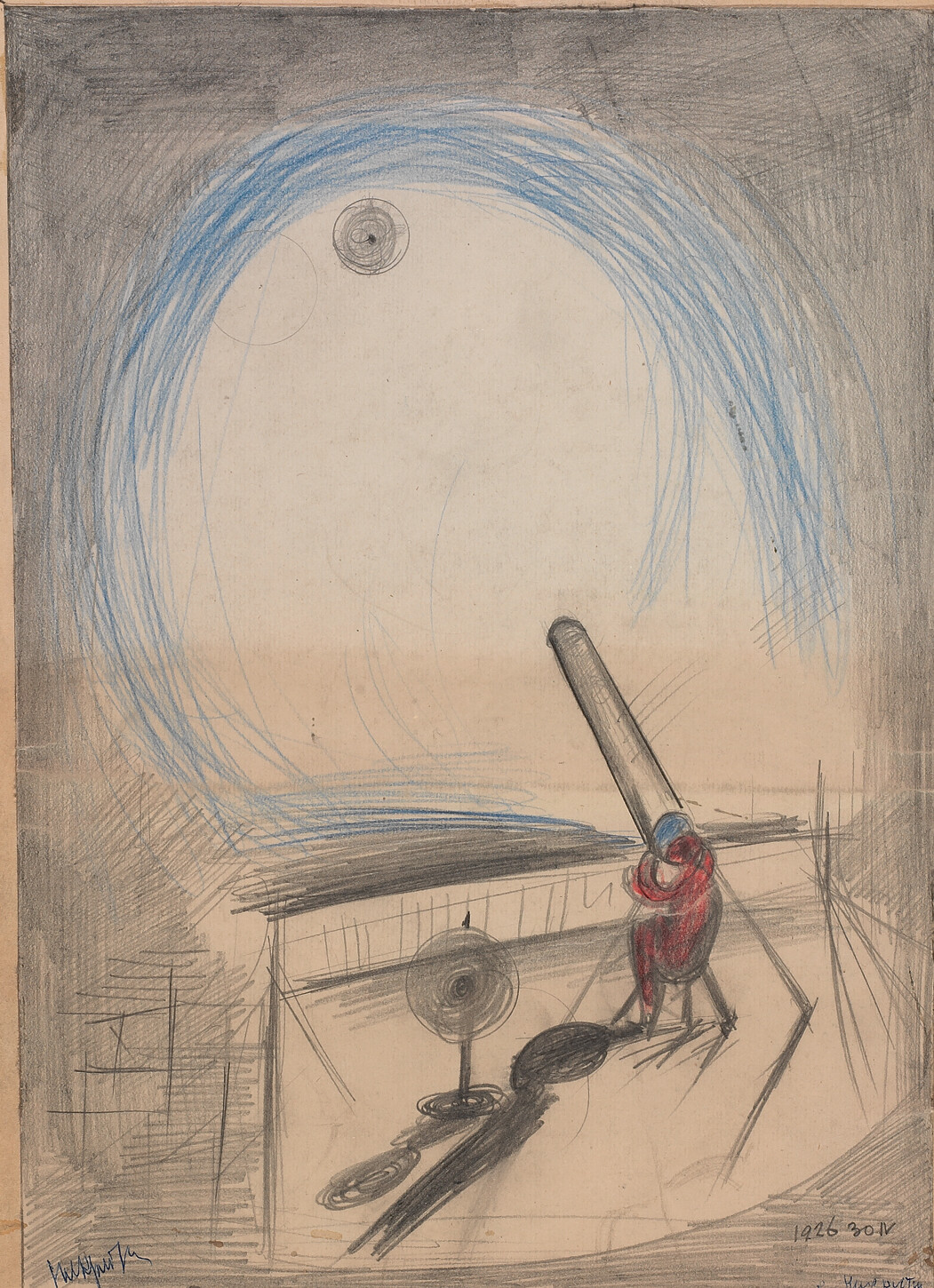

The so-called mystery-opera Victory Over the Sun, written and staged by the Russian futurists in 1913 (Alexei Kruchenych, Velemir Khlebnikov, Matyshin, Malevich), celebrates the imprisonment of the sun, the collapse of the cosmic order, and a kind of cosmic night in which all becomes possible. Here, indeed, chaos reigns. The usual chains of cause and effect are torn apart and life becomes unpredictable. In this chaos, only strongmen (silachi) can survive—actually, the futurists themselves. And the opera ends with the promise that the strongmen will live forever: their reign of chaos will never end. What guarantees the fulfillment of this promise? Nothing, actually.

The politicization of art mostly happens as a reaction against the aestheticization of politics practiced by political power. That was the case in the 1930s and it is the case now. For some time after the end of the Cold War, the political process seemed to be reduced to the tedious, boring work of administration. This bureaucratic work did not need art—and art was not especially interested in it. However, today politics has become a spectacle again. On its stage we see individuals who seem to have an artistic charisma of a certain kind. These individuals are celebrated but also passionately opposed. It is obvious that in this situation art cannot remain neutral, because politics has now entered the territory of art. It is also obvious that the contemporary art scene almost unanimously rejects the new populist movements and their leaders. This rejection has political reasons—but it has even deeper aesthetic reasons.

The way from neoliberalism to neofascism becomes clear enough. And this way is very short indeed. Both neoliberalism and neofascism believe in competition—this is what distinguishes them from international socialism. Neoliberals tend to think that they will always be the winners of this competition. The losers will be always the famous Other. Liberals are ready to preach recognition of the Other, respect for the Other, etc. But it seems that they can hardly imagine a situation in which they themselves become these Others.

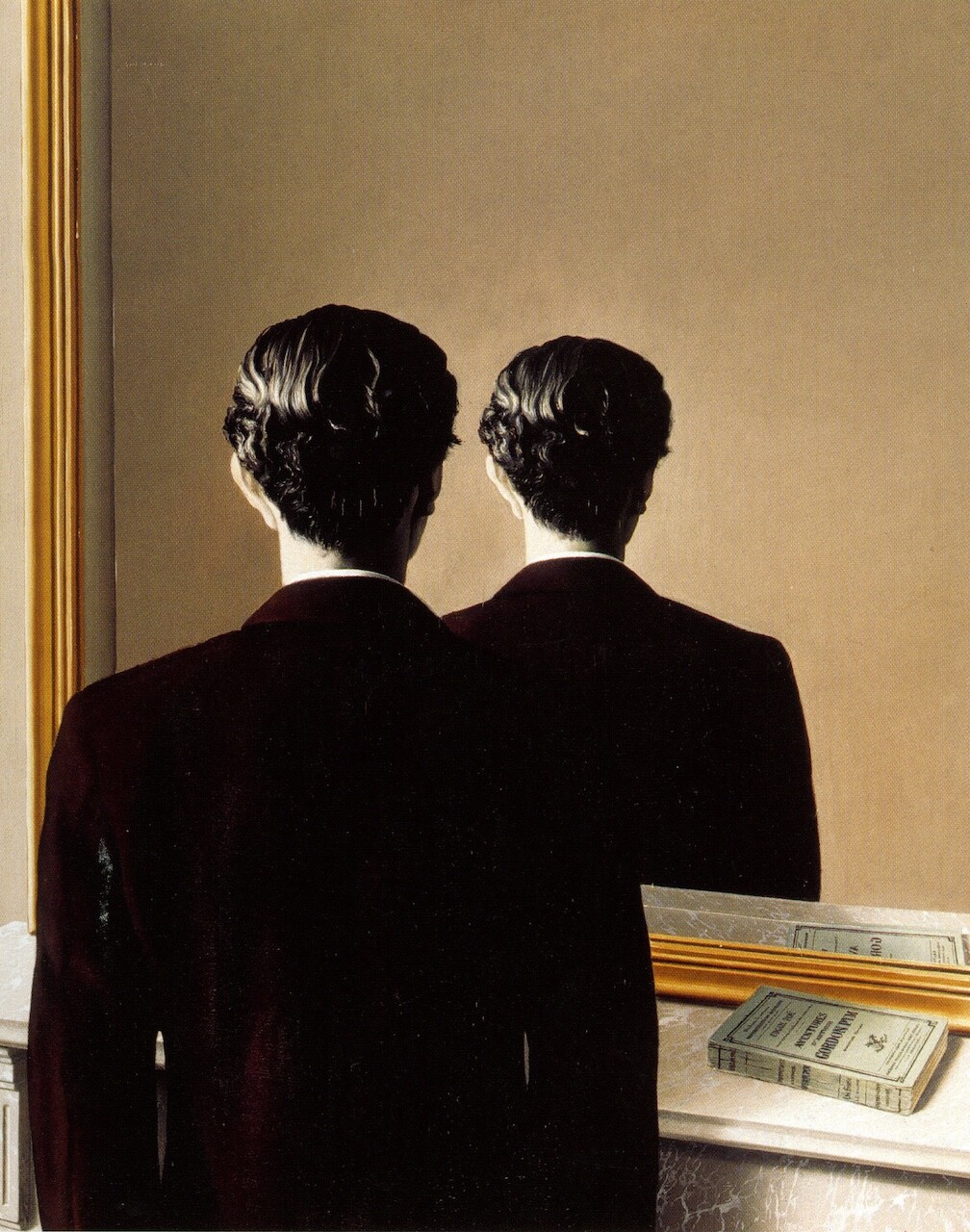

This status of the artwork as an object of contemplation is actually relatively new. The classical contemplative attitude was directed towards immortal, eternal objects like the laws of logic (Plato, Aristotle) or God (medieval theology). The changing material world in which everything is temporary, finite, and mortal was understood not as a place of vita contemplativa but of vita activa. Accordingly, the contemplation of artworks is not ontologically legitimized in the same way that the contemplation of the truths of reason and of God are. Rather, this contemplation is made possible by the technology of storage and preservation. In this sense the art museum is just another instance of technology that, according to Heidegger, endangers man by turning him into an object.

We initially discover reality not as a simple sum of “facts.” Rather, we discover reality as a sum of necessities and constraints that do not allow us to do what we would like to do or to live as we would like to live. Reality is what divides our vision of the imaginary future into two parts: a realizable project, and “pure fantasy” that never can be realized. In this sense reality shows itself initially as realpolitik, as the sum of everything that can be done—in opposition to an “unrealistic” view of the conditions and limitations of human actions. This was the actual meaning of nineteenth-century realist literature and art, which presented “sober” and elaborate descriptions of the disappointments, frustrations, and failures that confronted romantic, socially and emotionally “idealistic” heroes when they tried to implement their ideals in “reality.”