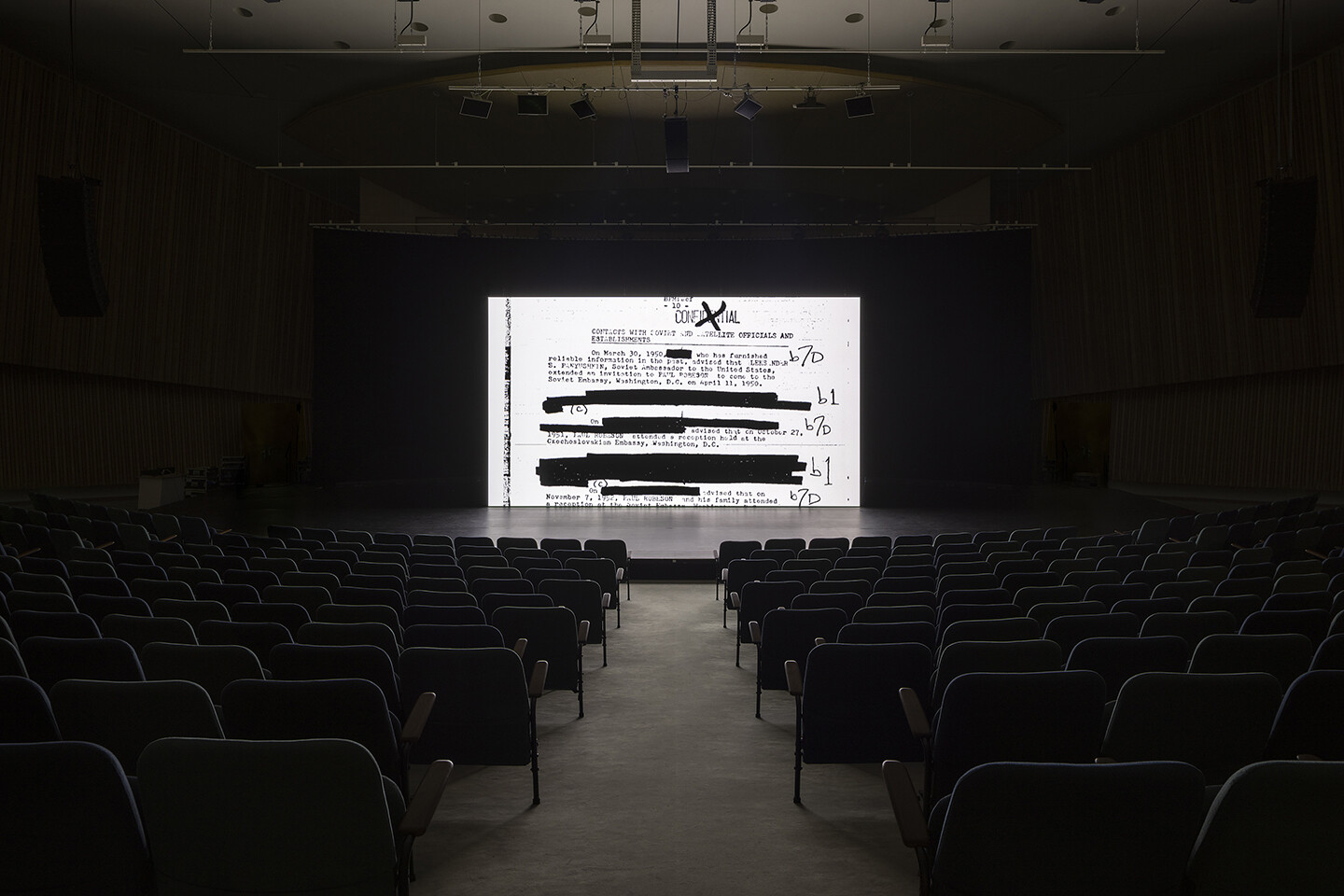

There was a structure. Things which were revealed were sealed. It was done in such an orderly fashion because, of course, these things were classified. Now they’re unclassified, but they’re still classified in a way because we don’t see all the evidence or facts that had apparently been gathered. It’s decorative to a certain extent: what is revealed and what is unrevealed, what is fact and what is fiction. So then it’s about what the spectator projects onto those files. The blackness was almost like holes within the system. Those holes tell you a lot about the failures of state surveillance, and more than anything, about the triumphs of the Robesons.

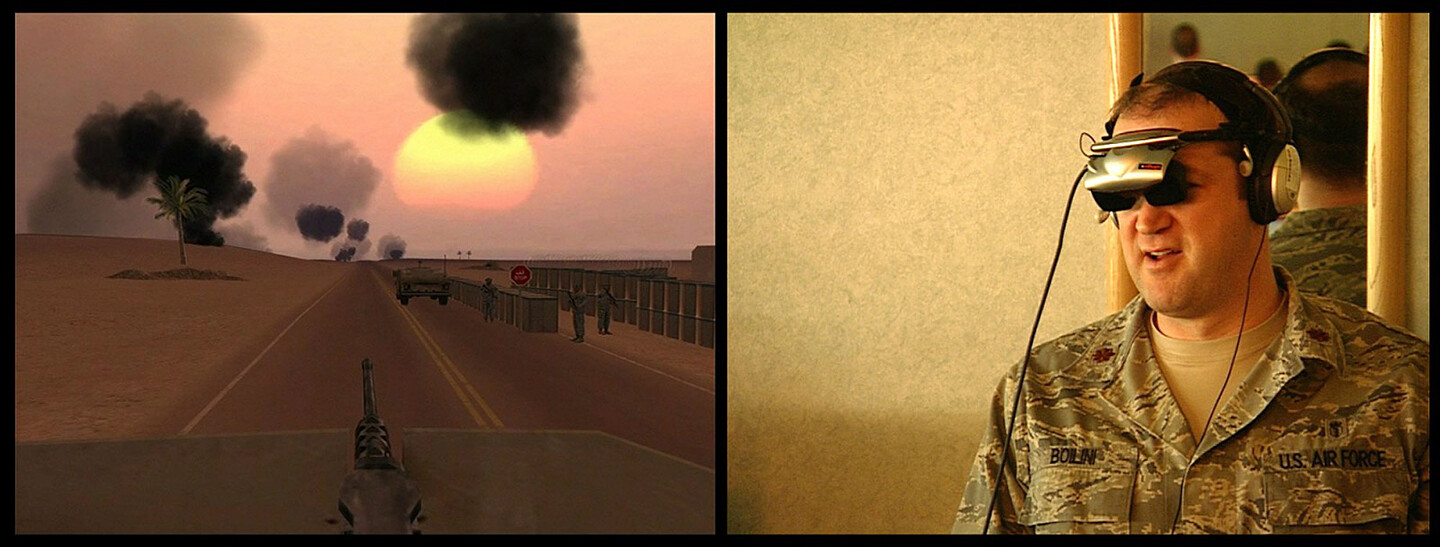

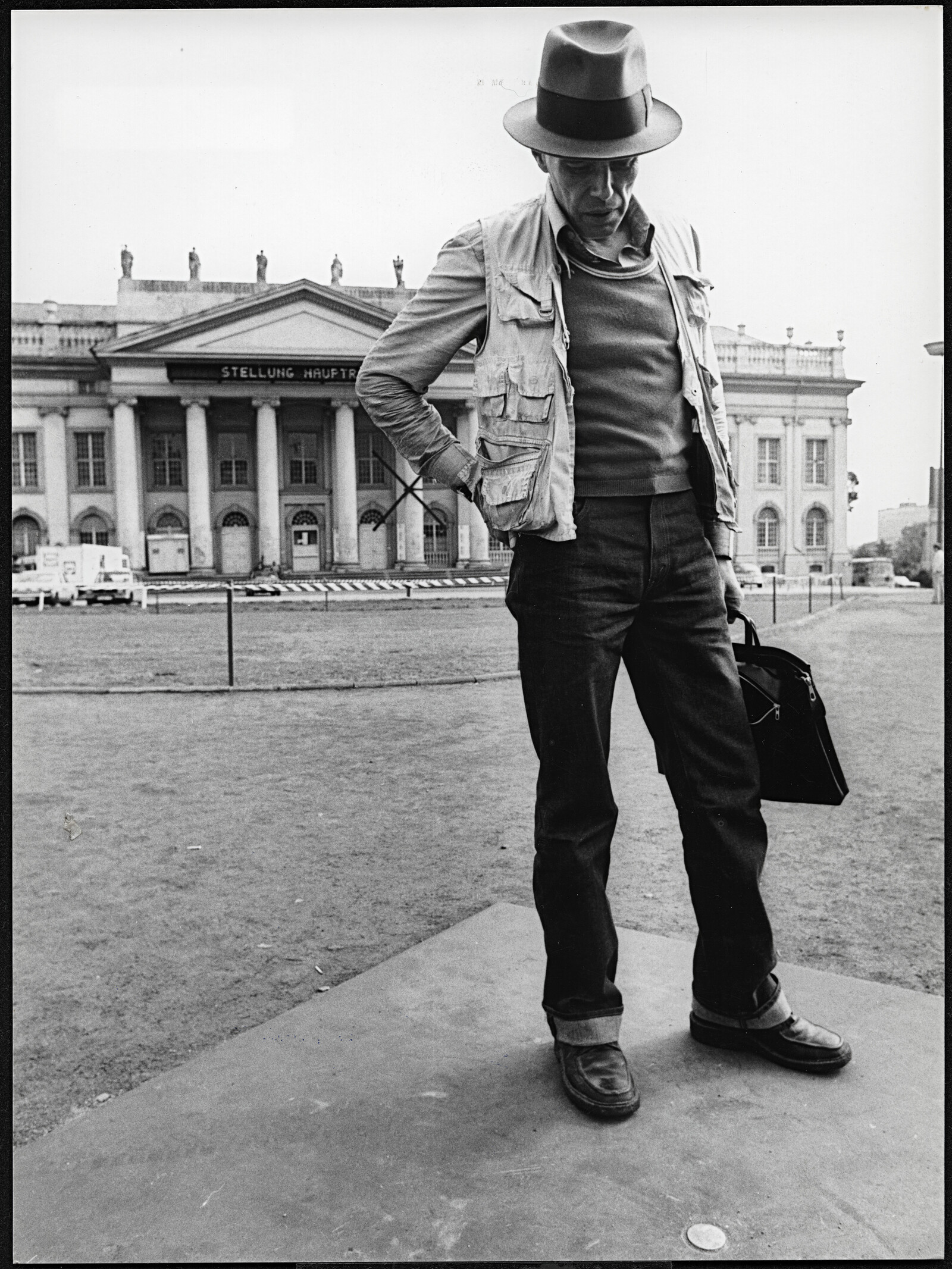

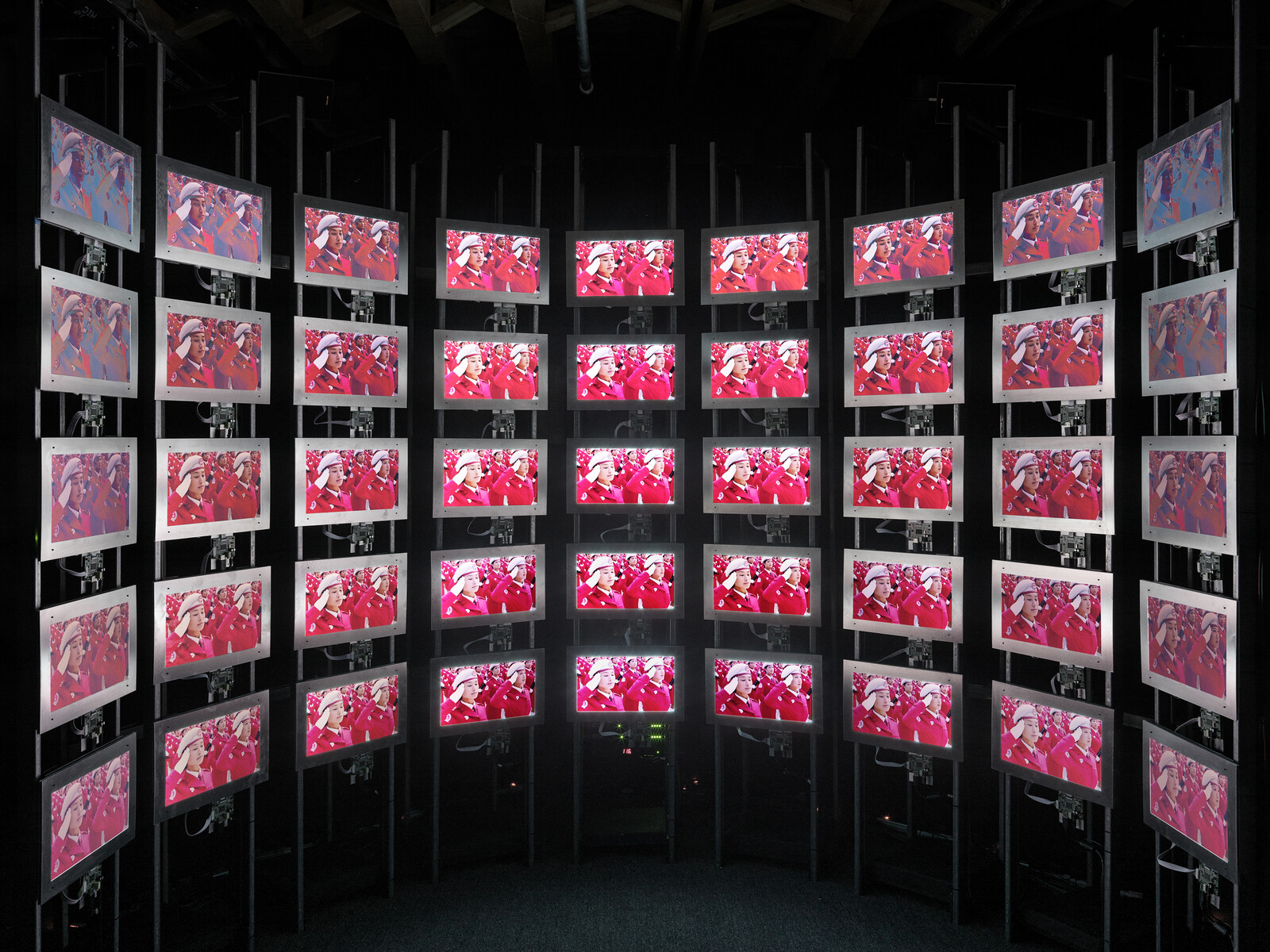

Coined by the renowned German filmmaker, artist, and writer Harun Farocki, the term “operational images” appeared in the early 2000s in his video installation trilogy Eye/Machine I-III (2001–3), which investigates autonomous weapon systems, machine vision in industrial and other applications, and the broader move from representations to the primacy of operations. Farocki’s film installation series presents this shift as a particular kind of image that emerges in those institutional practices, although it also articulates the shift through the various histories and spaces that condition both the emergence of such images and their industrial base: these include military test facilities, archives, laboratories, and factories.

The title of Anamika Haksar’s 2018 Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon (Taking the Horse to Eat Jalebis) comes from a line of dialogue in the film: when someone off camera asks a horse-cart driver what he’s doing, he replies that he’s taking his horse to eat jalebis, a traditional Indian dessert more popular with humans than equines. While the driver’s answer might seem sarcastic, it’s very much in earnest. With scenes like this, Haksar welcomes viewers to a world in which laborers speak and dream in ways that one might not expect, creating a realism that goes beyond standard notions of reality.