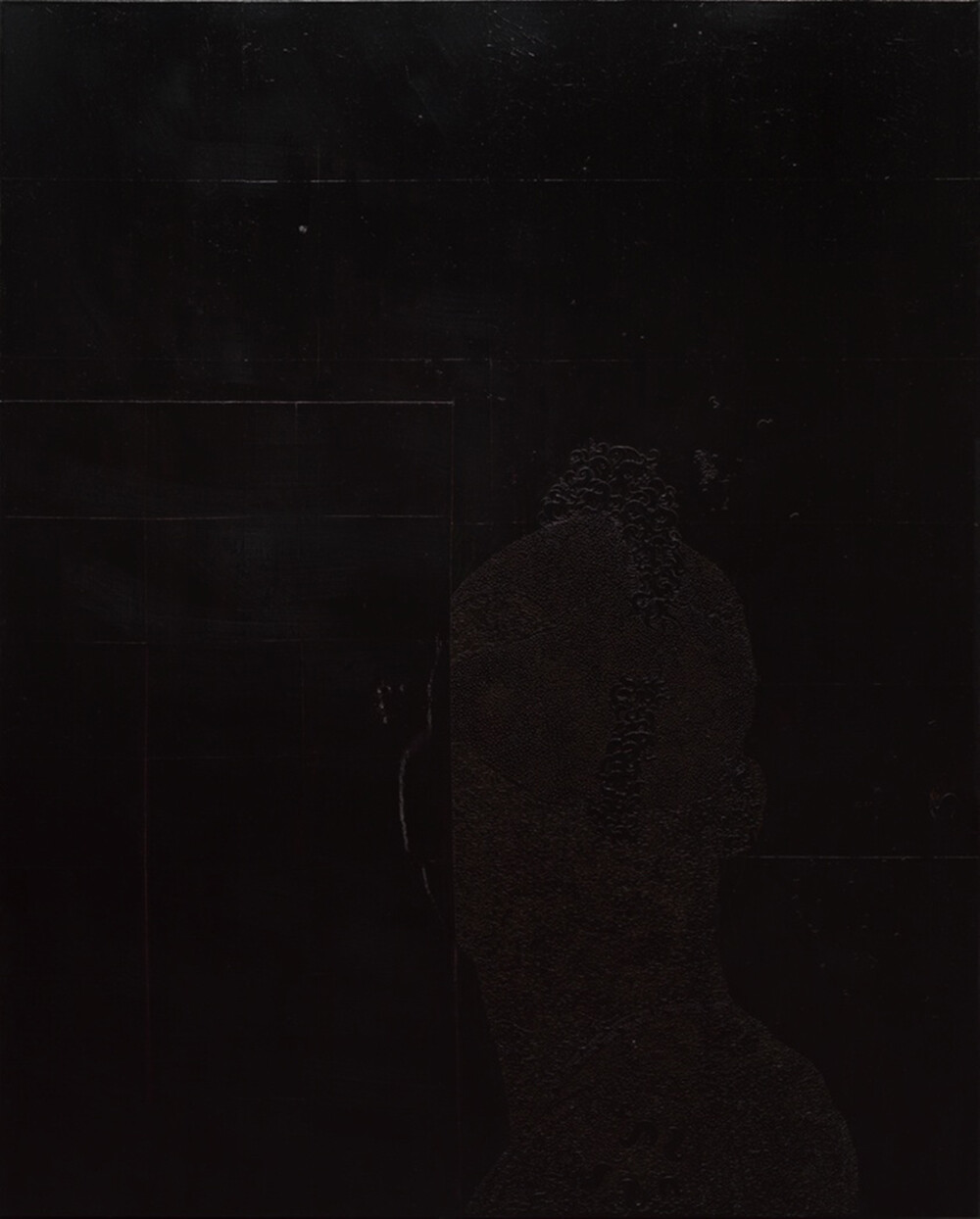

The unwieldy, internally variegated, and contested traditions that one might nevertheless nominate as black critical theory and black artistic practice, respectively, have had difficult relationships with various traditions of scholarly and aesthetic formalism (though these are, of course, hardly discrete designations). To begin with, the intellectual and artistic forms associated with blackness have typically been regarded by established traditions of formalism with, at best, skepticism.

Straub-Huillet at Work: A Screening of Harun Farocki’s and Pedro Costa’s Films

Some controversy emerges from amid the internality/transcendence dialectic. Precisely due to this unconscious realm, both artist and framework have the space to extend their own internality, activate their own vitality, and even deny their own staleness (陈腐) in order to open an orientation toward the future.

A series of visual essays to commemorate the tenth anniversary of e-flux journal

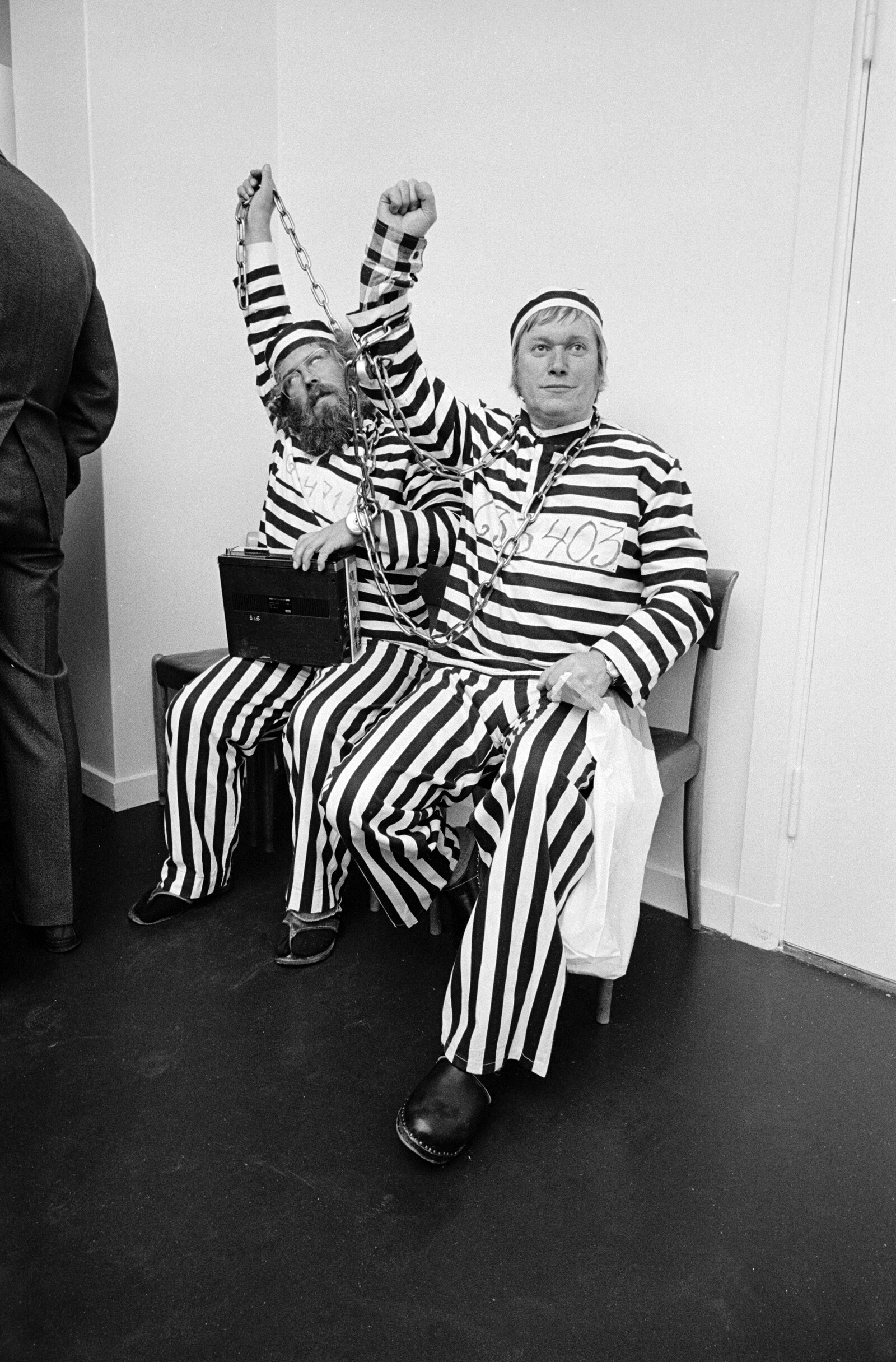

The rise of neo-Nashism serves as a peculiar, stinky example of a much broader, even global form of flesh-indulging fascism that circles around the historical avant-garde’s rotting corpse.

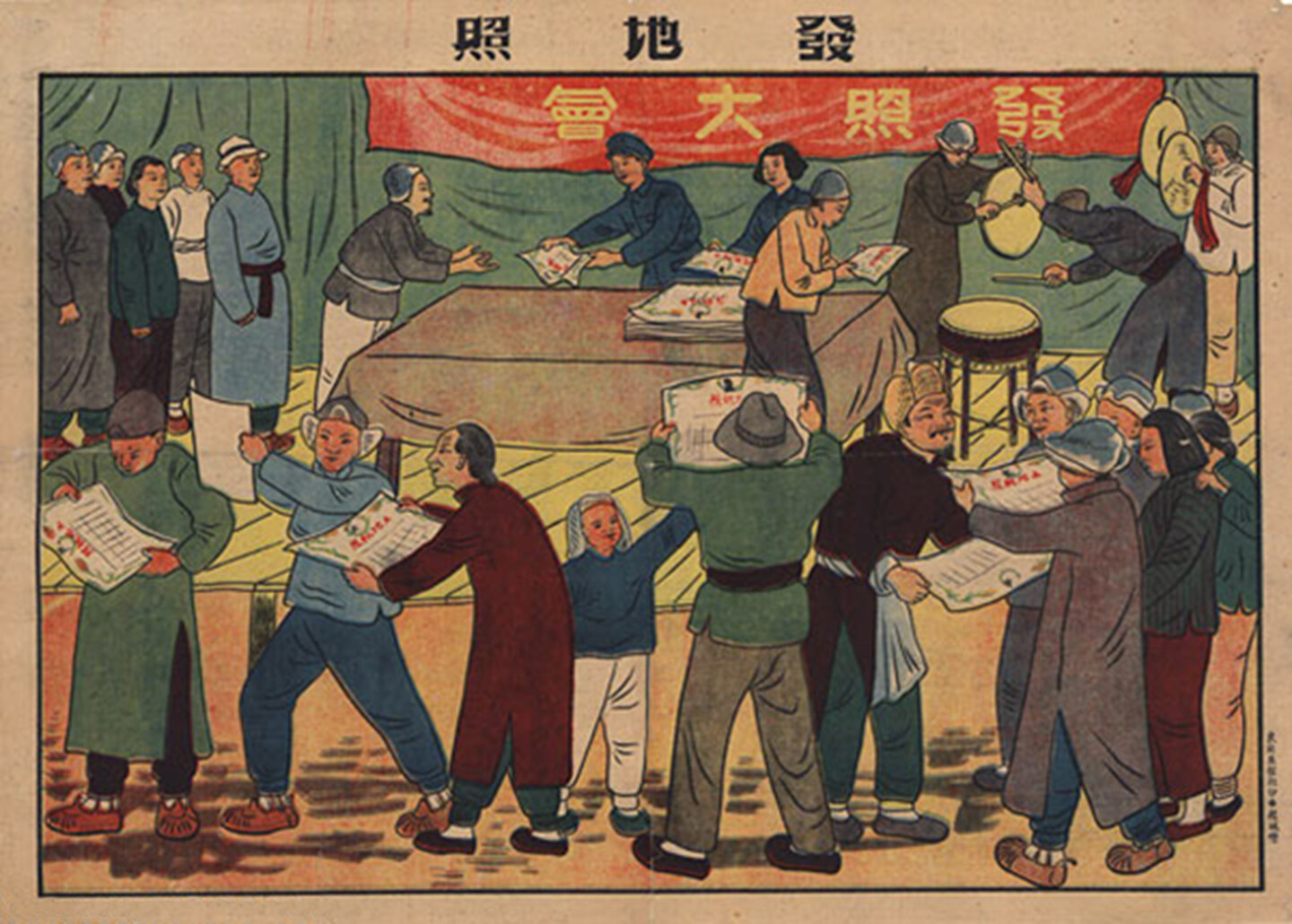

Although recognition of the artist as a creative individual is important, refusing to investigate the multidimensional nature of relationships and cultural interactions between the system and the people is tantamount to failing to attend to the pulse of history. Such practices can only result in an alienated past becoming an imaginative resource decoupled from history and present alike.

In his 1934 book Art as Experience, John Dewey understood the organism’s continuous negotiation with its environment in a related way. Sensuous experience, for the American pragmatist philosopher, is essential in the lessening of discomfort or the increase of well-being. It is integral to the aesthetic experience common to all life—an experience which gives rise to expressive forms and can be understood as the organismic precondition of art. Put another way, for Dewey, art is an artificial separation of the aesthetic sensibilities that suffuse and structure the experience of life-forms in the living world.

Maybe there are other ways of overcoming modernity that remain important for us today. War is not the most desirable thing, though it is always a possibility as long as the sovereign state remains the only reality of international politics, since sovereignty presupposes the possibility of war.

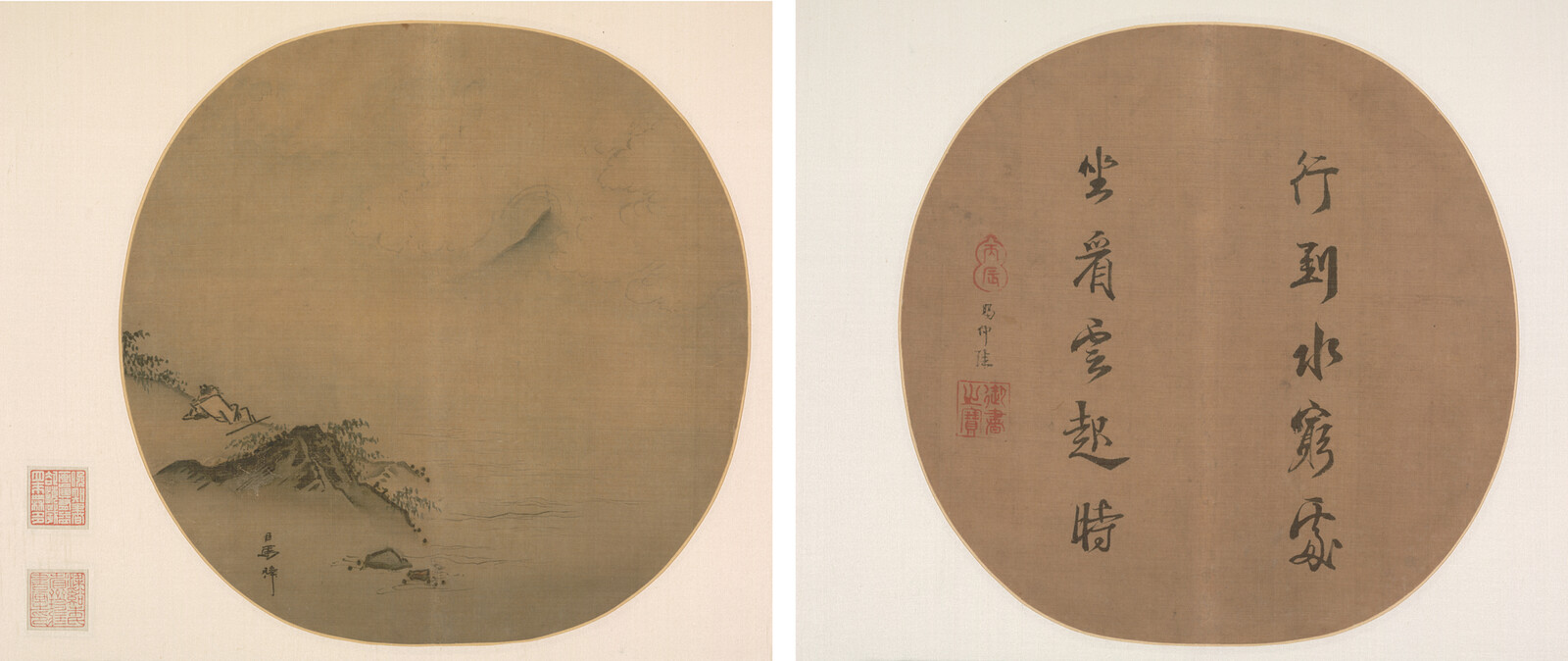

If, since Walter Benjamin—or even since the avant-garde before Benjamin—we have been trying to ask how technology changes the concept of art, as you find in Duchamp, can we now turn the question around and ask how art can transform technology? I think this is an important question not only in a conceptual sense, but also in a diplomatic one. If you were to talk to an engineer about an art project, how would you talk to them? Do you simply want to import this or that technology to create some kind of a new experience? Or do you want to influence how technology is made, how technology is conceived, how technology ought to be developed? I think we can also turn the question around further by asking: How can art contribute to the imagination of technological development?

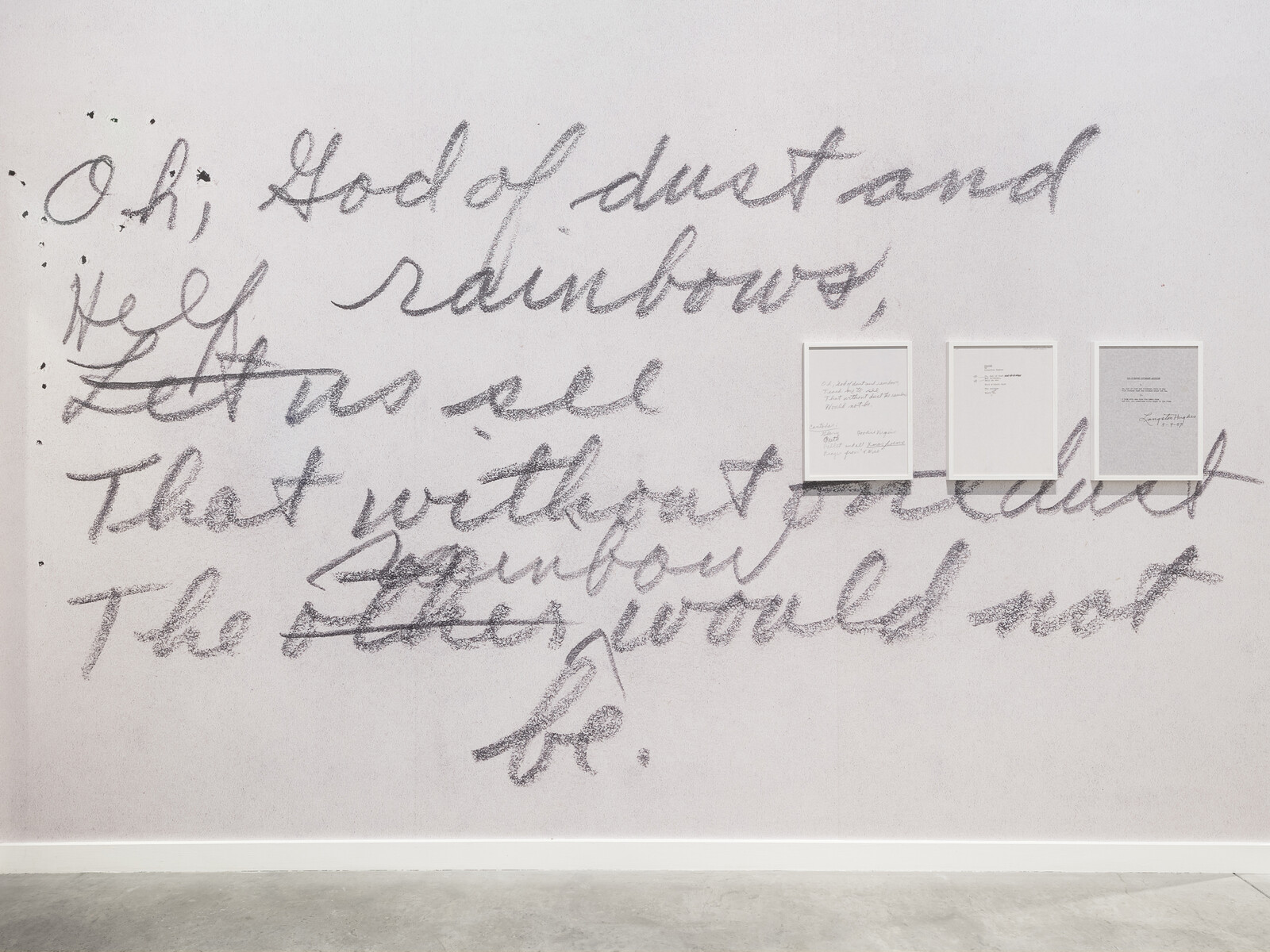

Art and Cosmotechnics

Yuk Hui

When the categorial force of blackness is confronted with the total violence that its historical trajectory cannot but recall, it cannot but refract and fracture the transparent shoal (the threshold of transparency) that protects the Subject’s onto-epistemology across his scientific and aesthetic moments. The total exposure of blackness both enables and extinguishes the force of the modern ethical program, insofar as the disruptive capacity of blackness is a quest(ion) toward the end of the world. Blackness is a threat to sense, a radical questioning of what comes to be brought under the (terms of the) “common.” If the ordered world secures meaning because it is supposed to be knowable, and only by Man, if that world is all the common can comprehend, then blackness (re)turns existence to the expanse: in the wreckage of spacetime, corpus infinitum.

The title of Anamika Haksar’s 2018 Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon (Taking the Horse to Eat Jalebis) comes from a line of dialogue in the film: when someone off camera asks a horse-cart driver what he’s doing, he replies that he’s taking his horse to eat jalebis, a traditional Indian dessert more popular with humans than equines. While the driver’s answer might seem sarcastic, it’s very much in earnest. With scenes like this, Haksar welcomes viewers to a world in which laborers speak and dream in ways that one might not expect, creating a realism that goes beyond standard notions of reality.

Online discussion with Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Anita Chari, and Soyoung Yoon, moderated by Irmgard Emmelhainz