The most interesting autotextual writing does one of two things, or even better, both: shows how selves are made, and makes room for a kind of self that otherwise barely gets to exist.

Only the living can visit the dead, not the other way around. We’re there when George Washington buys a slave. We’re there when a tree bears strange fruit. We’re there in the gas chambers, or when Winston Churchill starves to death millions of Indians. And as we in the present are in the past, we are also haunted by those in the future, those not yet born.

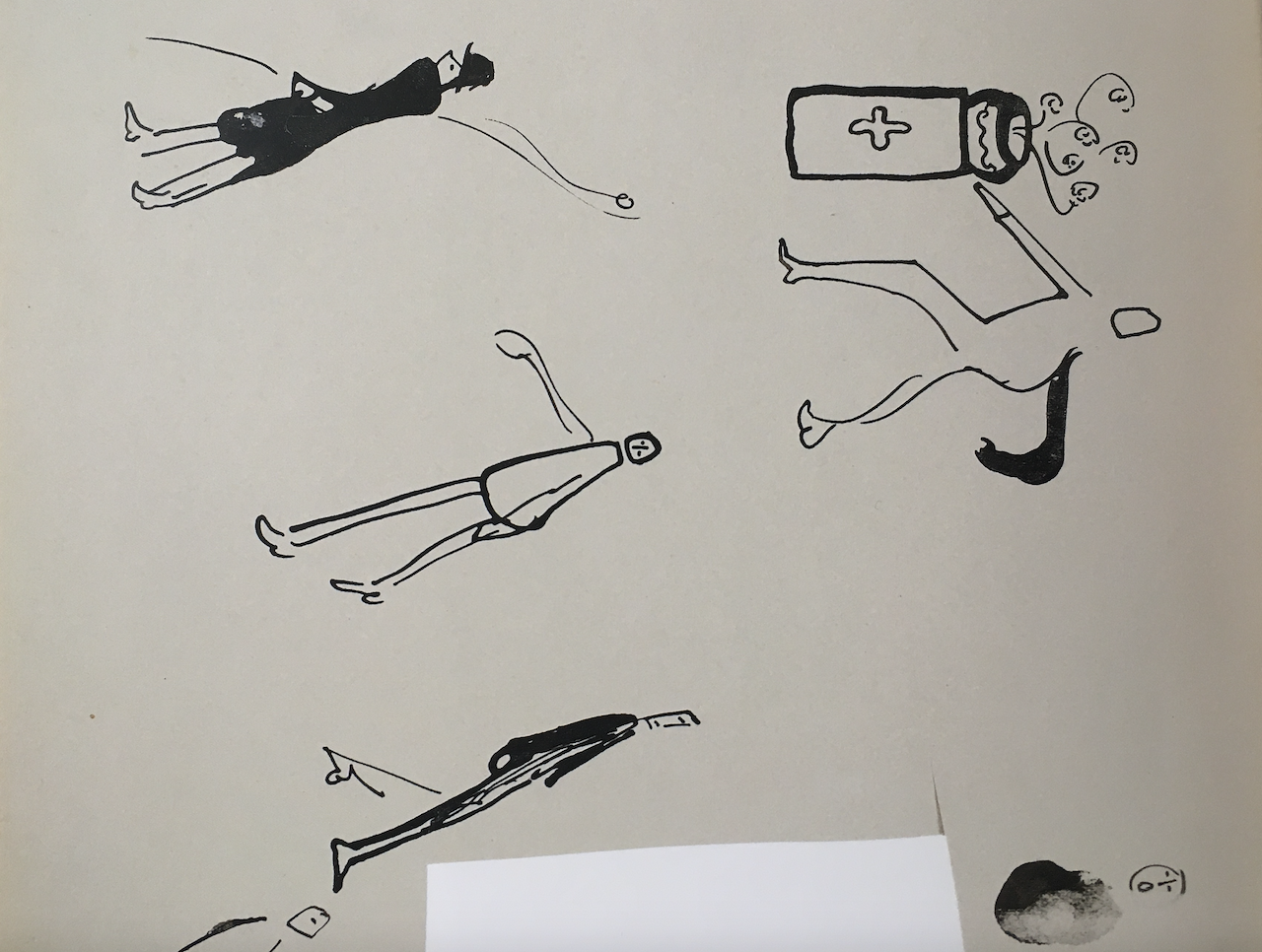

Back in the late ’80s, after the wrap-up of both Bambis, Natalya Bondarchuk relays that the animal doubles of the human actors were donated to the child survivors of the Chernobyl meltdown. In my head, I draw a misshapen map of the USSR; motion lines trace the relocation sites of irradiated children and the forever homes of the animal stars. But what of tonight’s nuclear battlefield? Is there a functional live webcam out there in the Zone of Alienation where I can tune into a shaking spider secreting a skewed lattice of sunlit gossamer strands—its bright irregular warp indicating persistent mutations in her body? Might I spy, with jaundiced, remote eye, the spider eating her own web? After a trauma-feed, she’s full (again) on her own distortions.

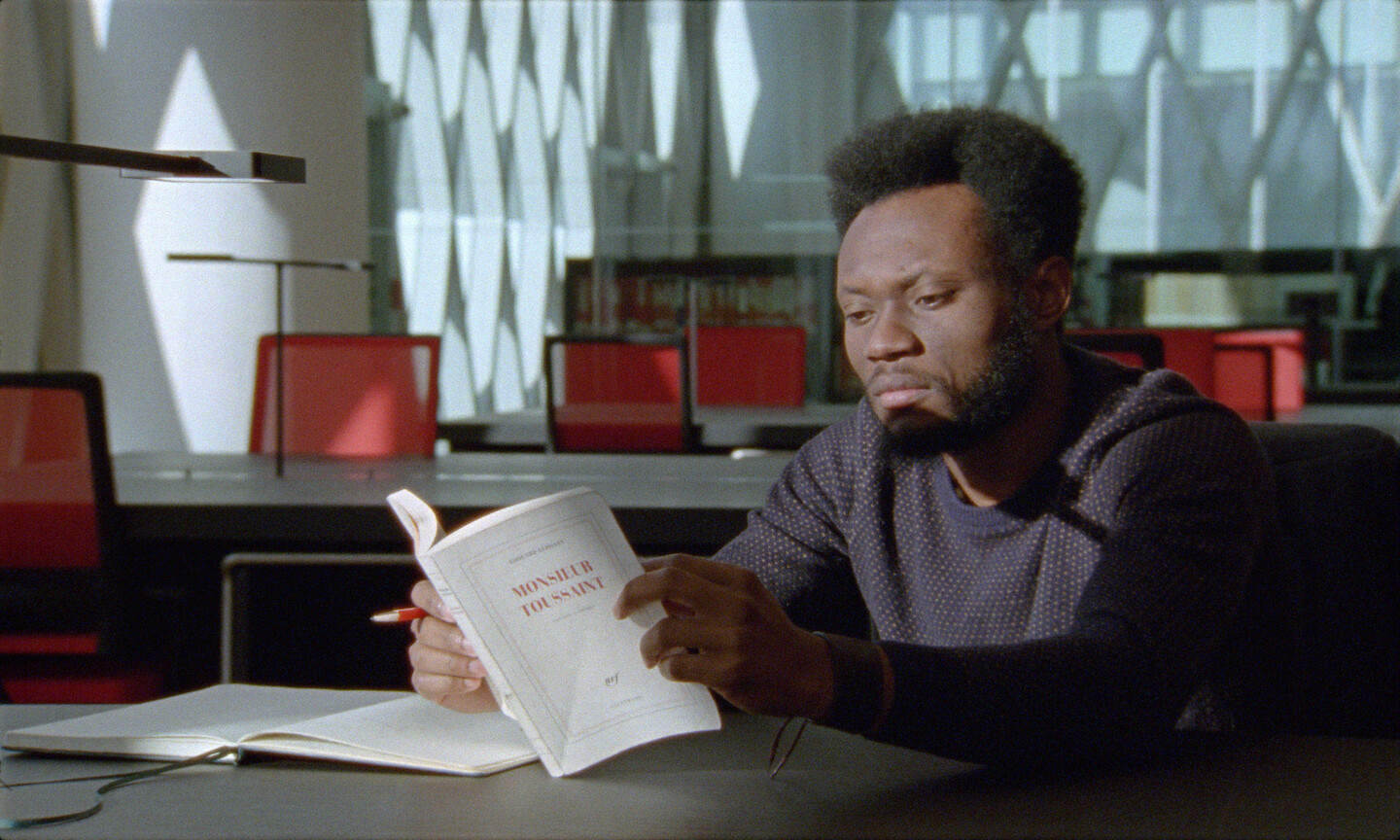

Louis Henderson: Ouvertures

Screening of Straub-Huillet’s Class Relations, with a talk by Annett Busch