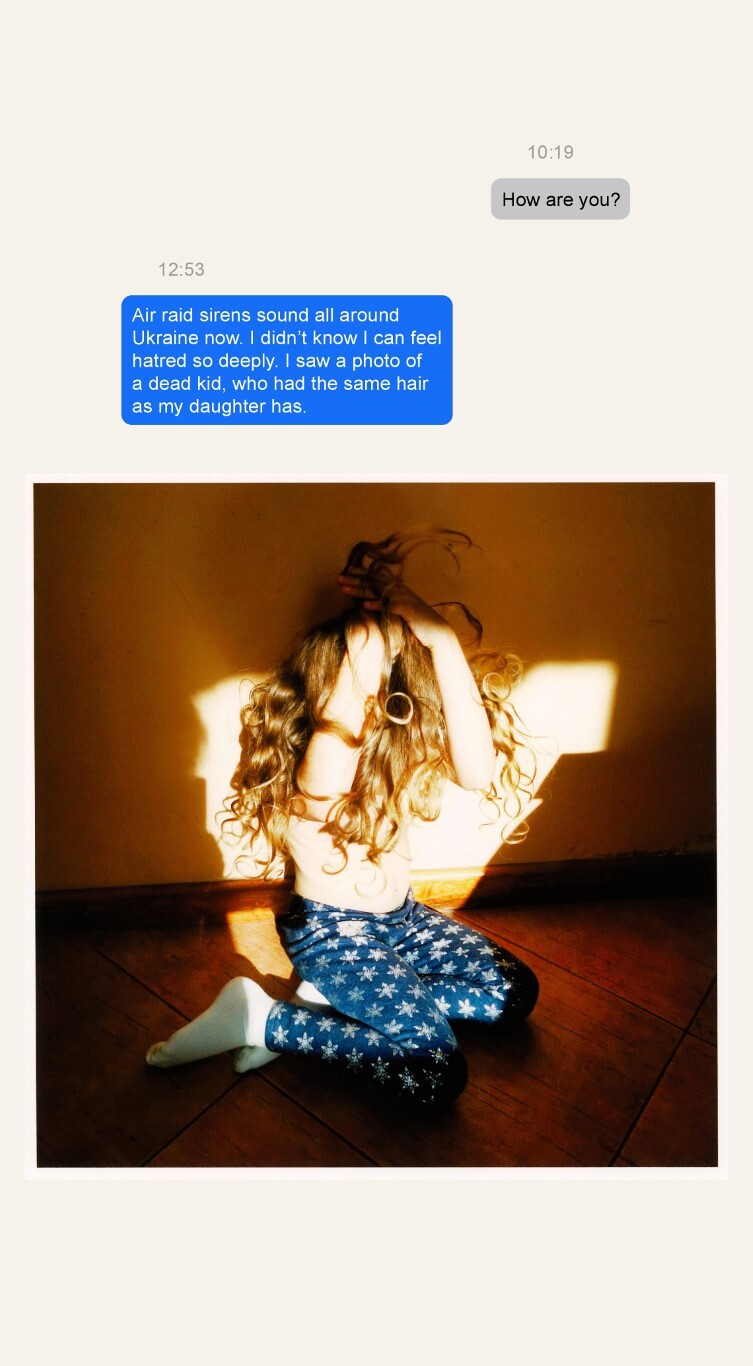

Anna Zvyagintseva, The Same Hair, 2022. Created for “Surface Encounters,” Galeria Municipal do Porto. Designer: Irina Pereira. Courtesy of the artists.

When the first explosion hit the Hostomil airport in the Kyiv region, I slept through it. However, all subsequent nights I could no longer sleep soundly: the sounds of planes, air defenses, and acute silence instead of a working siren reigned in my city of Irpin, which turned out to be the first front line protecting the capital. All subsequent days, despite the calls to go down to the shelter, I sat at the window under the balcony—in the only place where I somehow caught the internet and could read “hot” and urgent news. “Hot” is not even a euphemism anymore—many cities were on fire.

This morning, I caught myself thinking that I was not so much annoyed by the situation itself—sitting under the window and hiding from rockets—as much as by the fact that the video, which depicts the dead bodies of Russian soldiers, will not load and I cannot believe they are actually dead. I needed this brutal footage of doomed Russian military bodies for satisfaction. I have never felt so much euphoria and anger at the same time. A feeling of joy filled me: minus another murderer. It did not matter whose son this person was, whose husband, whose neighbor. First of all, for me, he was an occupier, a part of the military machine that destroyed my country and my life. My humanism was damaged with the first images of shelled civilians (the bombed Saltovka district in Kharkiv, where working-class housing is situated), with people shot while in line to buy bread in Chernihiv, with captured border guards from Zmiinyi Island. It seemed to me that there was no limit to my emotions. Perhaps this is precisely what war photographer Lee Miller felt when she filmed WWII. She published the horrors of war, such as the bodies of civilians torn to pieces by the Nazis, under the brutal title of “Nazi Harvest.” Today such content would be labeled as “sensitive,” like it was with all the Bucha massacre images and hashtags. But I would say Miller’s cruelty was proportional to the reality that she saw and lived—just like every photo from Bucha became an unbearable cry for help and justice.

During the first few weeks of full-scale war, I experienced a whole range of emotions that often existed in me in parallel, and I could not decide what I felt more. I could not understand my boundaries of rage, pride, hatred, panic, and tenderness. They were all raging at the same time.

At the beginning of her essay “On Violence,” Hannah Arent writes about intimidation as the best guarantee of peace—when the arms race and military buildup could guarantee peace. Of course, a lot has changed since this essay was written during the student protests of 1968. But even today, we have seen how the intimidation technique is applied: first there was the Russian military buildup near the borders of an independent country, and later there were air attacks, which the Ukrainian army has not always been able to stop. The Russian military aims at civilian infrastructure and expects to see people’s panic and fear. But the Ukrainians destroyed this paradigm, and despite their fear and high risks, they went out with their “bare hands” to sabotaged tanks, stole Russian military equipment, and drove Russian soldiers who came with guns out of their land and property. The more the Russian military wanted to evoke fear, the more the Ukrainians felt solidarity and strength. More precisely, speaking in Hannah Arendt’s terms, they felt their power. Describing the relationship between power and violence and noting these as non-coincident phenomena, she gives a prominent example of a clash between the Russian army and the nonviolent resistance of the Czechoslovaks in 1968. However, today a new history is being written in Ukraine. Such powerful resistance was clearly demonstrated in Ukrainian cities like Kherson, Kupiansk, Berdiansk, Konotop, and others, where local residents opposed the Russian military, expelling them from their homes and dehumanizing them. There is no doubt that this is an image of profound courage; however, it is also an example of how anger and hate unite people and allow them to fight. This is exactly the same anger I felt sitting under the window while waiting for a photograph of a dead Russian soldier. With each act that publicly demoralizes the invading military, each time a civilian speaks out against the occupiers, ordinary people manifest and consolidate their power. Perhaps that is why the figure of President Zelensky has become unifying. After all, he does not personify himself with force separate from the people but stands with everyone in the country. In each of his speeches, he emphasizes that everyone participates in the resistance, everyone fights.

I would like to return to one of the dominant emotions—rage, which Arendt also writes about. She believed that rage arises from a situation where there is reason to believe that certain conditions can change, but they do not change, in other words, when it seems to us that there is injustice, and it is not necessarily related to us personally. The active military aggression, the possibility of which President Zelensky spoke about publicly more than once, may not have been a surprise, at least for Ukrainians. We have been living in anxiety and fear of escalation of the war for several months. Therefore, this fact was not read as “injustice.” Instead, the fact that it is impossible to resist Russia by closing the sky and having no weapons to resist if it is possible—this fact was read as “a condition that must change.” So arming Ukraine has to be a priority today.

Justice is rooted in equality, which includes the possibility of a polyphony of voices, comprehension of different experiences, representation of political rights by a small self-organized community, and the establishment of equal conditions for the reproduction of their agency. In other words, Ukrainians have to have strong political and military force to resist Russian imperialism on many levels.

For a long time (and frankly speaking today), many international media outlets have been looking for neutral words to explain why Russia attacked Ukraine and started a full-scale war. However, what Moscow did was called war and seizure, violating international norms. The search for non-neutral words but the right ones is another way to establish justice. For example, in the 1780s, the empress of Russia, Catherine the Great, resettled Greeks from the Crimea peninsula to steppes near the Sea of Azov (part of present-day Donetsk Oblast). However, these “resettlements” were just a “neutral” and comfortable word for “deportation.” The same thing is happening today: Russia is deporting the inhabitants of Ukraine who lived in Mariupol and other occupied cities to its territory. And replacing them with Russians. These is not mere migration, not the resettlement of people of their own free will; this is forcing them to leave by violent means.

Another way to restore justice is to protect cultural heritage and return it to the territory of Ukraine. Here are a few examples. The Russian military has mined unique monuments of geology and archeology of world importance, such as the Park of the Stone Graves, located near Melitopol, Zaporizhzhia Oblast. This monument contains a unique rock painting from the late Paleolithic to the Middle Ages. In addition, the landscape itself is iconic and preserves evidence of the existence of the Sarmatian Sea. Another example is the museum of the incredible artist Maria Primachenko, which came under fire. The guardian of the museum took the works out of the fire, risking his own life and, fortunately, he saved all of them. One more example is the museum of Arkhip Kuindzhi in Mariupol, which first came under fire, and then the works of many artists (including Arkhip Kuindzhi, Ivan Aivazovskyi, and others) were taken to Russia. And finally, Russia shelled the Kharkiv city center and tried to destroy crucial constructivist architectural heritage. Such brutal events point toward other evidence of past violence. Reading the history of art today, we see the mass killing, persecution, and censorship of the Ukrainian intelligentsia in 1937–38, in the 1950s, and again in the 1970s. We also see artworks depicting deportation, displacement, massacres, famine, and other horrors portrayed by Ukrainian artists today who look at testimonies of past persecutions.

Justice concerns the Ukrainian language and traditions introduced by the dominant Russian culture. Today we see evidence of how Russian policy is again planning to retrain Ukrainian children in the occupied territories.

Justice concerns economic repression and the export of Ukrainian resources outside the country. Ukraine already remembers the tragedy of the Holodomor, which happened from 1932 to 1933. An artificial famine, the Holodomor was accompanied by incredible violence against the inhabitants of Ukrainian villages.

Justice is also dedicated to the memory of the Babi Yar tragedy. On September 29, 1966, thousands of Kyivans went to a rally in Babi Yar in Kyiv to commemorate the 1941 massacre of Jews by Nazi soldiers there. Among them were writers Viktor Nekrasov and Ivan Dziuba, film director Heliy Snegirov, and artists Ada Rybachuk and Volodymyr Melnichenko. However, the rally was suppressed, and Nekrasov, who organized it, was accused of organizing a “Zionist meeting.” Many of those present were demoted or had their work censored. On March 1, 2022, a Russian missile hit the site of Babi Yar.

Justice can compensate for the suffering of Ukrainian women raped, wounded, and killed during the war. Before my eyes are an Irpin woman resident who was found dead because she was run over by a tank; a middle-aged woman from Bucha who signed up for a manicure course before the war; an eight-month-pregnant woman from Mariupol who escaped on foot from the city. And many other women who died and survived under horrible circumstances. This essay was written on behalf of all of them.

Some of my international colleagues try to hide their rage, saying that Ukrainians are too emotional, too unstable. But we have objective reasons to feel such strong emotions. And the main reason is European slowness and neutrality. Unfortunately, peace will not come suddenly; it is a slow, grueling process—and Ukrainians understand this more than ever because they already have experience fighting for their freedom.

Our rage is rooted in the history of oppression of Ukrainian arts and culture for centuries by Russian policy and culture. It is deeply connected with the mass killings and persecution of Ukrainians over centuries. Therefore, the history of Ukrainian art has to be revised to highlight depictions of violence and tyranny. This is how the complete image of our loss and grief will become clear.

To us, peace is an efficient thing. But, unfortunately, it will not come from reading poetry or watching a movie, and even less so from potential Russian-Ukrainian discussion (sick!), where there can be nothing but populist conversations. Peace will come only when one person gives another person his bulletproof vest, like a Ukrainian soldier did in Irpin city to protect a child. Or when a peaceful city is protected by an air defense system. Or, finally, when Russian troops leave Ukrainian territory, including occupied areas in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, and when Crimea again becomes an autonomous republic within Ukraine, so Crimean Tatars who left their hometowns are able to return. And many other people who left their homes will come back too.

Indeed, many Ukrainians escaped from the war. However, many of us stayed and are waiting for the war to be over. We are not refugees. We are passengers who are waiting for the right train, which will bring us back to our cities and our lives. The solution to the “Ukrainian migration crisis” directly depends on the end of the war. It’s not a crisis; it is evidence of the Russian war.

Rethinking my experience, I was trying to write a letter to Hannah Arendt, to search for answers to questions about the humanism of the twenty-first century, about humanism during war and genocide. I was wondering how aggression towards the occupier is connected with love—such as the love I feel for the people (whom I have never met) who survived the incredible horror of the bombing of the Mariupol Drama Theater. Or the love I feel for those with whom I escaped the city under shelling, feeling fragments of weapons and destroyed infrastructure fly past our backs.

Anna Zvyagintseva, The Same Hair, 2022. Created for “Surface Encounters,” Galeria Municipal do Porto. Designer: Irina Pereira. Courtesy of the artists.

There have been many powerful visual images that have passed before my eyes lately. One of the most powerful is a photograph of an older man from Zaporizhzhia hugging and comforting a newborn baby. You can see everything in this older man’s eyes: pain, sadness, disappointment, humility, peace, and love. He transfers all his experience, knowledge, and feelings to this little child who has survived an unjust war. It’s an incredible gift. This is how generation after generation should pass on their culture and heritage.

In fact, love makes people join the army; love becomes a reason why a woman does everything so that her beloved does not go to the first line of defense; it is love that makes people rescue animals from fire and shelling.

During the first weeks of the war, I felt the need to protect people and give them what I had enough of and what I lacked. In fact, love and care are something I can share with people. However, I’m not just talking about partners’ or parents’ love; I’m talking about a more comprehensive feeling. The feeling of support, care, and unity. Not about obsessive or passionate love, but about love in which everyone is equal. When even weaker ones cover the weak with their bodies.

I believe that love and empathy are principles of how civil society is built and what makes our community stronger in this struggle. Undoubtedly, the need for self-organization arises since the state, for various reasons, is not able to solve some problems. However, it is not just about the volunteer movement but also about being in the rear guard, and about everyday practices. For example, I recently interviewed a journalist who hid in the subway during the first days of the full-scale war; he said a stranger gave him his blanket before the evacuation. Therefore, I can say that I am grateful that our government does not control our love, care, and our desire for intimacy. I think it is this freedom that makes us stronger as a society.

“You are too emotional to make a decision,” said my European colleague.

Yes, we are emotional, but there is nothing more stable than our belief in justice and law. And eight years of war taught us this. My love is born in grief and sorrow, and thanks to my rage, it becomes even stronger.

One lesson of the twenty-first century is the ability to afford vulnerability. We should allow ourselves to feel anger, rage, and anxiety, to live it as necessary. And then, with a sense of lived grief, we can rethink the concepts of humanism and the conditions of peace. After all, as we already know, not a single document signed by world leaders can protect any country from imperial encroachments and incredible violence—even one that gives nonaggression guarantees.

***

I collected my backpack with a calm mind, understanding that it was impossible to take everything valuable with me. I took documents and casual things because you don’t know where the road will take you. I also took sneakers that my old Donetsk friend from Irpin gave me a month earlier. They fit perfectly! Two months after full-scale war, I am still walking in her shoes. And I am still wondering, how many people can experience the same?

This text was written on March 20. Final revisions were made on May 9.